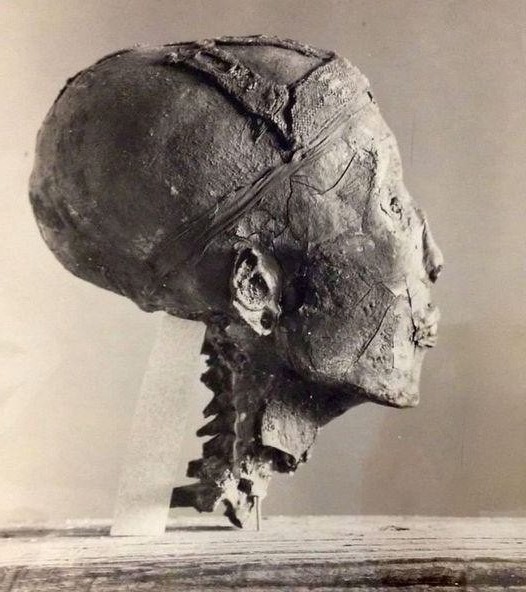

King Tutankhamun’s mummy could not be separated from the coffin since the resins and unguents had penetrated the wrappings, adhering the body itself to the coffin. Ultimately, the body had to be chiseled out. The torso was cut in half at the level of the hips to remove the pelvis and legs from the coffin. The arms were disarticulated at the shoulders, elbows, and wrists in order to continue the unwrapping of the torso and to remove bracelets; each body part was treated with H๏τ paraffin wax to stabilise it. The hands and feet were later reattached with resin. Lastly, H๏τ knives were used to remove the head and neck from the mask. To view the condition of the teeth, Derry made an incision around the inner edge of the jaw and across the throat; this damage was repaired with resin. This thorough disarticulation of the body “gave clear views of the ends of each of the relevant bones, allowing the anatomists to make an accurate estimate of the king’s age”.

The Case of Tut’s Missing Collar

below the whole group and at the lowest level before reaching the skin, was a bib-like Collarette composed of fine green faience & gold bead matting having a zigzag pattern.…This bib covers the whole of the upper part of the chest as far as the clavicles.—Howard Carter, November 15, 1925

<ʙuттon class="lightbox-trigger" type="ʙuттon" aria-haspopup="dialog" aria-label="Enlarge image: SO22 Digs Egypt Tut Mummy" data-wp-init="callbacks.initTriggerʙuттon" data-wp-on-async--click="actions.showLightbox" data-wp-style--right="context.imageʙuттonRight" data-wp-style--top="context.imageʙuттonTop">

<ʙuттon class="lightbox-trigger" type="ʙuттon" aria-haspopup="dialog" aria-label="Enlarge image: SO22 Digs Egypt Tut Mummy" data-wp-init="callbacks.initTriggerʙuттon" data-wp-on-async--click="actions.showLightbox" data-wp-style--right="context.imageʙuттonRight" data-wp-style--top="context.imageʙuттonTop">Three years, almost to the day, after archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.) in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings, he removed the pharaoh’s mummy from its coffin and unwrapped a layer of linen bandages. Underneath, he saw a splendid collar on the chest of the young king where it had been placed more than 3,000 years before. PH๏τographs taken by excavation pH๏τographer Harry Burton nearly a year later show the collar still in place when the mummy was returned to the coffin. But when it was X-rayed in 1968, the collar was gone, and the mummy was badly damaged where the piece had once lain. For the past seven years, Egyptologist Marc Gabolde of Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 University has been trying to find the collar—or what remains of it—and discern whether Carter took any part of it himself. “When I began my book about Tutankhamun a decade ago, I realized I had to address the question of objects that were diverted by Carter,” Gabolde says.

Some early excavators in Egypt had permission to take a selection of artifacts back to their home countries, a system called partage, or “division,” but Carter had no such agreement with the Egyptian government for Tutankhamun’s tomb. Everything he found was supposed to remain in Cairo to be stored or displayed in the museum there. Carter died in 1939, and his niece, Phyllis Walker, was responsible for disposing of his property. The auction house Spink & Son prepared a probate list with valuations of artifacts found in his collection, 20 of which were identified as having belonged to Tutankhamun. In 1946, Walker gifted some of these artifacts to King Farouk of Egypt, who in turn gave them to the Cairo Museum. “They could not be returned, per se, because they were never supposed to have left in the first place,” says Gabolde. Other objects from Carter’s collection had already been sold by Spink, including—almost certainly, says Gabolde—other artifacts from Tutankhamun’s tomb.