At North Carolina State University, a research project is changing our understanding of medieval history. The team extracts DNA from old parchment documents. Tim Stinson, an ᴀssociate professor of English and University Faculty Scholar, leads this study. It has an impact on how experts study historical manuscripts. They now look beyond the written words to unlock genetic data hidden within the materials

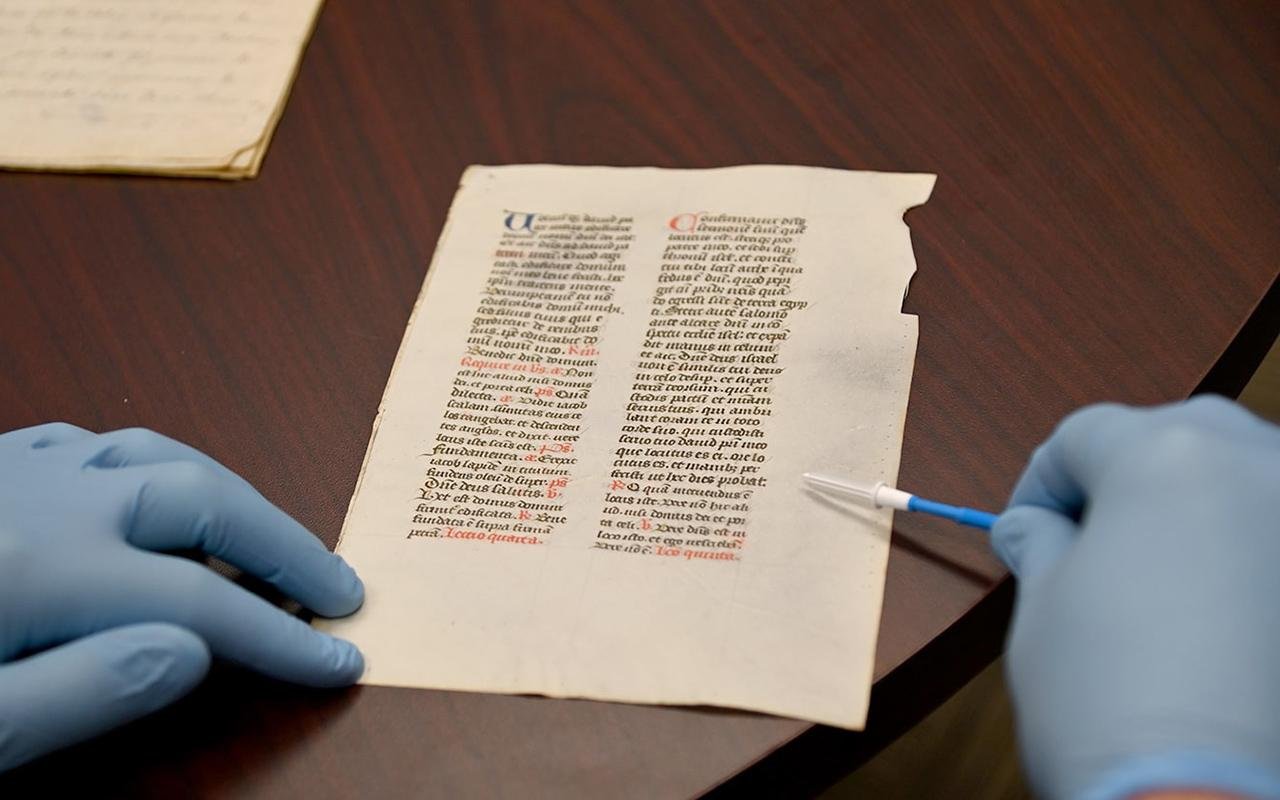

Collecting cellular material with a cytology brush is faster, easier and less invasive than using an eraser. Credit: North Carolina State University

Collecting cellular material with a cytology brush is faster, easier and less invasive than using an eraser. Credit: North Carolina State University

In the past, humanities researchers looked at the text in historical documents. But Stinson and his team have come up with a new way to study them. They combine manuscript studies with advanced scientific methods. Working alongside colleagues from NC State’s College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM), the researchers have validated a noninvasive method for collecting DNA from parchment without harming these valuable artifacts.

Previously, researchers relied on a time-consuming method that used PVC-based erasers to gather cellular material for DNA extraction. This approach was not only slow and physically exhausting but also risked cross-contamination. Looking for a better way, the researchers developed a less intrusive, more efficient approach.

The team found that cytology brushes, commonly used in medical tests for cervical cancer, provided a better option. These gentle brushes collect cell material from parchment surfaces without leaving visible marks, unlike erasers, which can remove dirt and the document’s appearance. Their study, published in PLOS One, showed that this technique could successfully extract mitochondrial genomes from parchment as old as the eighth century.

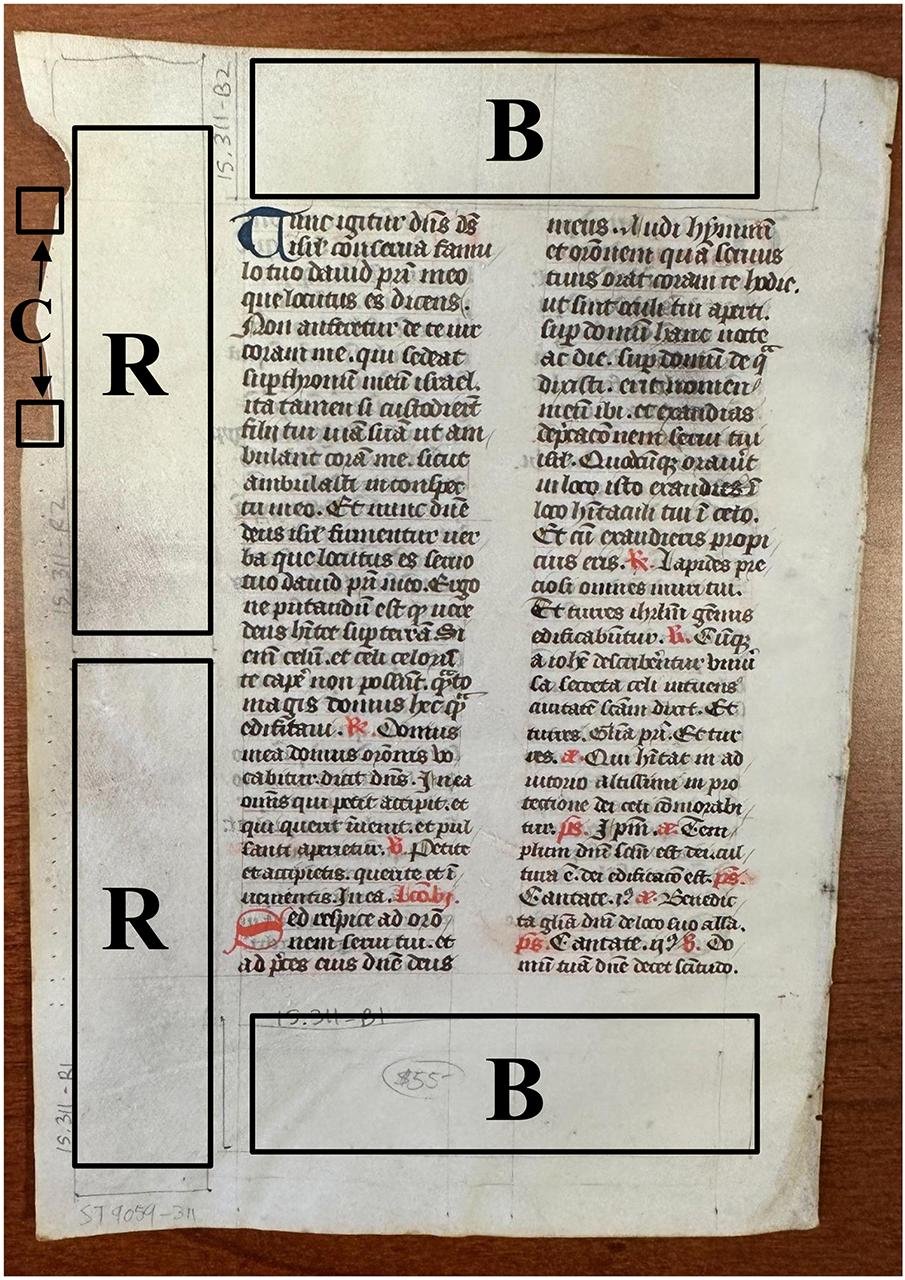

Strategy for sampling both destructively (cutting, “C”) and non-destructively (brushing, “B”; rubbing, “R”) from parchment documents. Ceedit: M. Scheible et al., PLoS ONE (2024)

Strategy for sampling both destructively (cutting, “C”) and non-destructively (brushing, “B”; rubbing, “R”) from parchment documents. Ceedit: M. Scheible et al., PLoS ONE (2024)

The team gathered about 300 parchment samples from different historical documents to check if the technique worked well across different time periods and regions.

Parchment, made from animal skins, was the primary writing surface before the advent of paper. The DNA in these documents can offer valuable insights about the livestock used to make manuscripts, breeding practices, and even the environment that affected these animals. When scientists extract genetic material, they can determine the species, Sєx, and microbiome of the animals. This might shed light on farming and economic practices in medieval times.

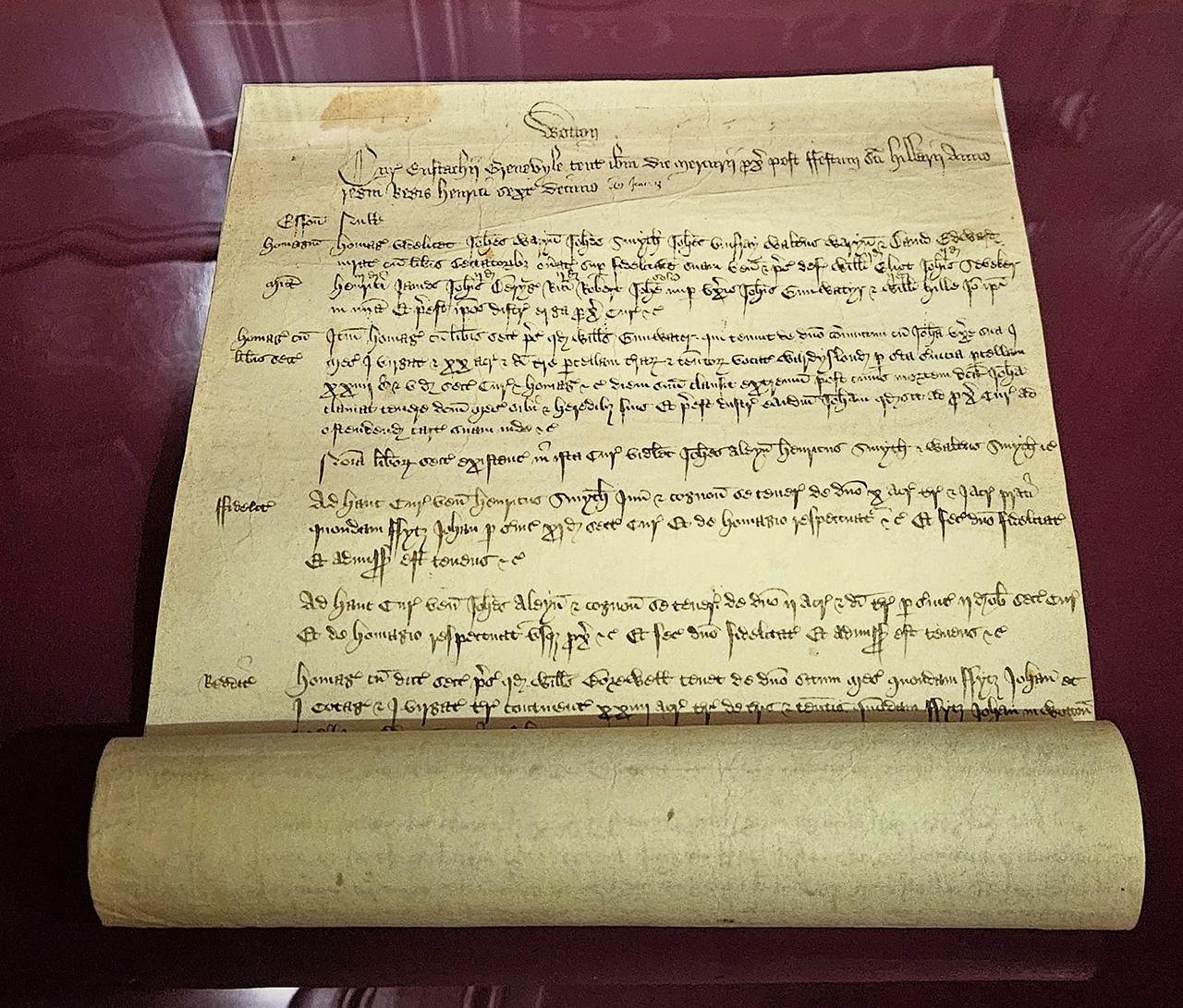

Now, the team has set its sights on a type of parchment that hasn’t received much attention: manor court rolls. Feudal estates in medieval Europe kept these documents to record legal proceedings, land transactions, births, and deaths. Manor court rolls were continuously expanded by sewing new parchment sheets together. Sometimes, this resulted in scrolls that covered more than 200 years of local history.

Court Roll for the Court of Eusace Grenville in Wotten Underwood, Buckinghamshire – Manuscript on parchment, England, May 30, 1430-September 7, 1431. On display at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, USA. Credit: Eric Polk, CC BY-SA 4.0

Court Roll for the Court of Eusace Grenville in Wotten Underwood, Buckinghamshire – Manuscript on parchment, England, May 30, 1430-September 7, 1431. On display at the Huntington Library, San Marino, California, USA. Credit: Eric Polk, CC BY-SA 4.0

The research team’s work positions NC State at the forefront of an emerging discipline known as biocodicology. This area examines biological clues preserved in historical manuscripts. By combining genetic studies with historical records, scientists can dig into how diseases spread, climate conditions, and even epidemics that affected medieval populations.

In the next few months, the team plans to analyze manor court rolls from insтιтutions like the Harvard Law Library, the Folger Shakespeare Library, and the Norfolk Record Office. What they find might give us a better grasp of life in medieval times and help historians, scientists, and archaeologists uncover long-lost aspects of human history.

More information: North Carolina State UniversityScheible M, Stinson TL, Breen M, Callahan BJ, Thomas R, Meiklejohn KA (2024) The development of non-destructive sampling methods of parchment skins for genetic species identification. PLoS ONE 19(3): e0299524. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0299524