A recent study using Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) technology has uncovered the true magnitude of Guiengola, a 15th-century Zapotec city in southern Oaxaca, Mexico. Previously believed to be a military fortress, the site has now been identified as a fortified city covering 360 hectares, consisting of over 1,100 structures and surrounded by defensive walls and a mᴀssive urban layout.

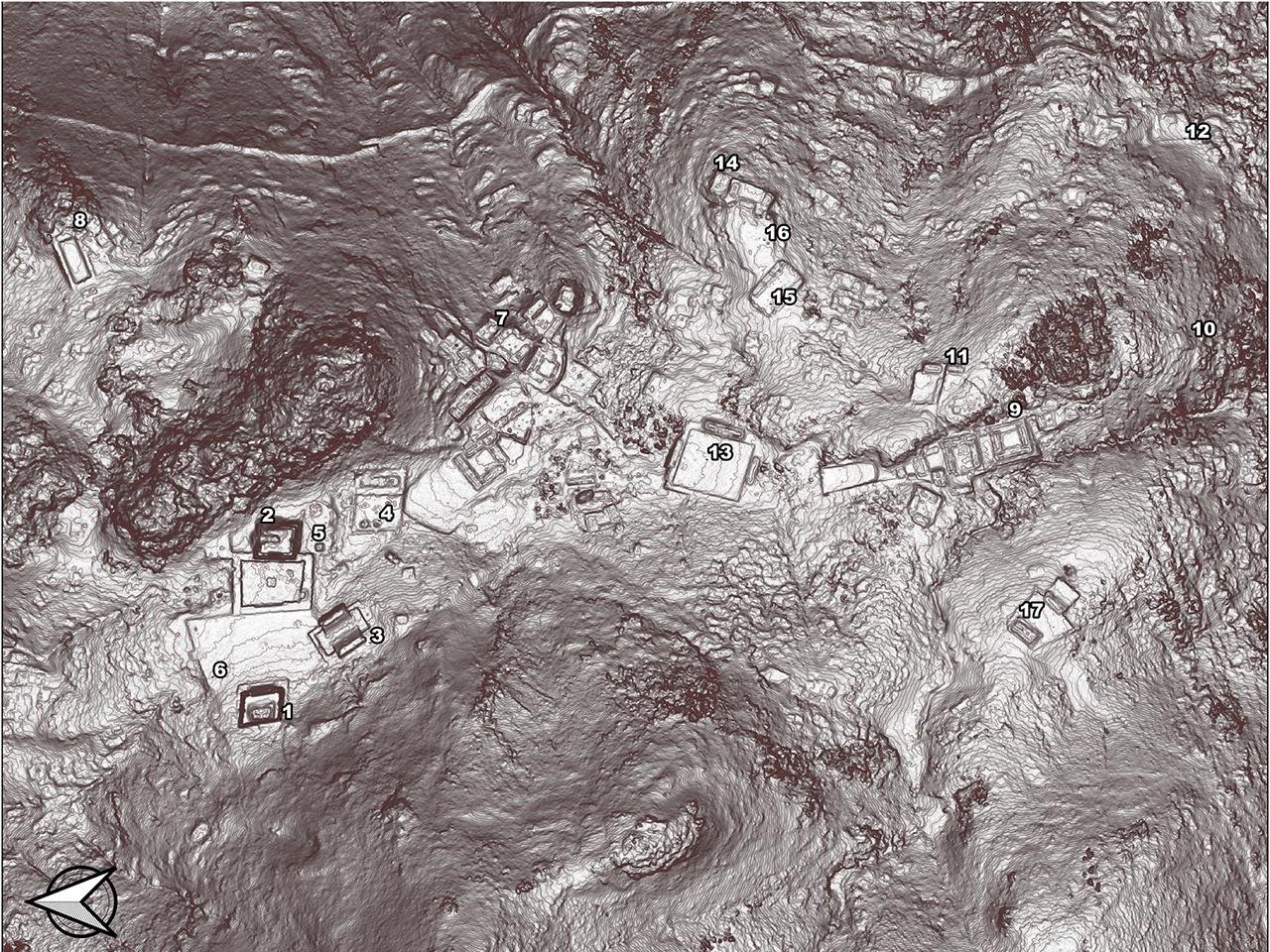

Epicenter of the city. The biggest buildings of the city were found in this area surrounded by the main wall. Credit: Ramón Celis PG., Ancient Mesoamerica (2024)

Epicenter of the city. The biggest buildings of the city were found in this area surrounded by the main wall. Credit: Ramón Celis PG., Ancient Mesoamerica (2024)

Led by archaeologist Pedro Guillermo Ramón Celis of McGill University, the research found that Guiengola, or “Large Stone” in Zapotec, was much more than a military outpost: The site possesses temples, ball courts, distinct residential zones for elites and commoners, and a complex system of roads and strongholds.

“Because the city is only between 500 and 600 years old, it is amazingly well preserved. You can walk there in the jungle and find that houses are still standing—you can see the doors, the hallways, and the fences that separate them from other houses,” said Ramón Celis in a statement. “It’s like a city frozen in time before any of the deep cultural transformations brought by the Spanish arrival had taken place.”

Guiengola played a significant role in the power wars of the late 15th century. An indigenous pre-Columbian civilization, the Zapotecs, who emerged around 700 BCE, faced growing pressure from the Aztec Empire. The last major confrontation between the Zapotecs and the Aztecs occurred at Guiengola between 1497 and 1502 CE when the Aztec emperor Ahuizotl launched a protracted siege that lasted seven months. Despite fierce resistance from the Zapotecs, Guiengola was eventually abandoned, and its inhabitants moved to the nearby community of Tehuantepec for better access to water and arable land. Their descendants still live there today.

Guiengola, Oaxaca, Mexico. CC BY-SA 3.0

Guiengola, Oaxaca, Mexico. CC BY-SA 3.0

LiDAR technology, which uses laser pulses to create detailed 3D topographic maps, was instrumental in uncovering Guiengola’s full extent. Before this, the dense forest canopy covered much of the site and made traditional archaeological surveys impossible. “Until very recently, there would have been no way for anyone to discover the full extent of the site without spending years on the ground walking and searching. We were able to do it within two hours by using remote sensing equipment and scanning from a plane,” Ramón Celis explained.

The study has also shed light on the social and political layout of Guiengola. By identifying a spatial pattern in the distribution of structures, researchers have begun to distinguish areas set aside for elite and religious activity, including temples and ball courts. The fact that the Zapotecs organized such a complex and strategically significant city suggests a high level of political sophistication and autonomy, challenging previous ᴀssumptions regarding their relationship with the Aztecs and, later, the Spanish colonizers.

Snake sculpture found and described by Seler (1904), now at the Oaxacan hall in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Credit: Ramón Celis PG., Ancient Mesoamerica (2024)

Snake sculpture found and described by Seler (1904), now at the Oaxacan hall in the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Credit: Ramón Celis PG., Ancient Mesoamerica (2024)

Due to a personal connection with the region, Ramón Celis intends to continue investigating Guiengola: “My mother’s family is from the region of Tehuantepec, which is around 20 km [12 miles] from the site, and I remember them talking about it when I was a child,” Ramón Celis explained. “It was one of the reasons I chose to go into archaeology,” he shared. His team is set for its fourth field season, during which it plans to document the 1,170 structures identified by LiDAR. The project will not involve excavation but rather will rely on other remote sensing techniques.

More information: Ramón Celis PG. Airborne lidar at Guiengola, Oaxaca: Mapping a Late Postclassic Zapotec city. Ancient Mesoamerica. 2024;35(3):899-916. doi:10.1017/S0956536124000166