In a recent study, a team of international experts has revolutionized our understanding of chicken domestication and its journey from the jungles of Southeast Asia to becoming one of the world’s most populous animals. This research offers fresh insights into the domestication of chickens, their spread across Asia, and the evolving role they played in societies over the past 3,500 years.

Credit: Oleksandr P

Credit: Oleksandr P

Contrary to previous beliefs that chicken domestication dated back 10,000 years in regions such as China, Southeast Asia, or India, the latest findings challenge these ᴀssumptions. The driving force behind chicken domestication was not found in Europe over 7,000 years ago, but rather in Southeast Asia. It was the introduction of dry rice farming in this region that initiated a close ᴀssociation between people and the red jungle fowl, the wild ancestor of today’s chickens.

This domestication process began around 1,500 BCE in the Southeast Asian peninsula. The study reveals that chickens were transported across Asia and then throughout the Mediterranean, following the trade routes used by early Greek, Etruscan, and Phoenician maritime traders.

During the Iron Age in Europe, chickens were not primarily considered a food source but rather venerated. Early chickens were often buried individually and un-butchered, with male chickens buried alongside cockerels and female chickens with hens. It wasn’t until the Roman Empire that chickens and eggs gained popularity as food. In Britain, chicken consumption didn’t become widespread until the third century CE, primarily in urban and military areas.

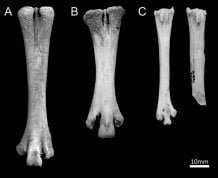

The international team of experts meticulously re-evaluated chicken remains from more than 600 sites across 89 countries. They scrutinized skeletal remains, burial locations, and historical records to understand the societal contexts in which these bones were discovered. The oldest domestic chicken bones were found in Neolithic Ban Non Wat in central Thailand, dating between 1,250 and 1,650 BCE.

Radiocarbon dating was employed to determine the age of 23 proposed early chickens found in western Eurasia and northwest Africa. The results have debunked claims of chickens in Europe before the first millennium BCE, suggesting that they did not arrive until around 800 BCE. After their arrival in the Mediterranean region, it took nearly 1,000 years for chickens to establish themselves in colder climates like Scotland, Ireland, Scandinavia, and Iceland.

The two studies, published in the journals Antiquity and The Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, were conducted by experts from various universities, including Exeter, Munich, Cardiff, Oxford, Bournemouth, Toulouse, and others in Germany, France, and Argentina.

Professor Naomi Sykes from the University of Exeter notes, “Eating chickens is so common that people think we have never not eaten them. Our evidence shows that our past relationship with chickens was far more complex, and that for centuries, chickens were celebrated and venerated.”

Professor Greger Larson, from the University of Oxford, emphasizes, “This comprehensive re-evaluation of chickens firstly demonstrates how wrong our understanding of the time and place of chicken domestication was. And even more excitingly, we show how the arrival of dry rice agriculture acted as a catalyst for both the chicken domestication process and its global dispersal.”

Dr. Julia Best, from Cardiff University, highlights the groundbreaking use of radiocarbon dating, stating, “This is the first time that radiocarbon dating has been used on this scale to determine the significance of chickens in early societies. Our results demonstrate the need to directly date proposed early specimens, as this allows us the clearest picture yet of our early interactions with chickens.”

Professor Joris Peters from LMU Munich and the Bavarian State Collection of Palaeoanatomy points out the role of sea routes in the chicken’s global spread, stating, “With their overall highly adaptable but essentially cereal-based diet, sea routes played a particularly important role in the spread of chickens to Asia, Oceania, Africa, and Europe.”

Dr. Ophélie Lebrᴀsseur, from CNRS/Université Toulouse Paul Sabatier and the Insтιтuto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano, emphasizes the startling fact that despite their ubiquity today, chickens were domesticated relatively recently. She underscores the importance of robust osteological comparisons, secure stratigraphic dating, and placing early finds within their broader cultural and environmental context.

Professor Mark Maltby, from Bournemouth University, highlights the significance of museums and archaeological materials in unraveling our past. These studies demonstrate the value of historical artifacts in shedding light on the complex history of our relationship with chickens, from veneration to a staple in our diets. — University of Exeter.