A team of experts from the University of California, Davis and Drew University believe they have solved the puzzle of why people throughout the Roman Empire used lopsided dice in their games.

Jelmer Eerkens and Alex de Voogt present their study of dice used during the Roman Empire in their paper published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

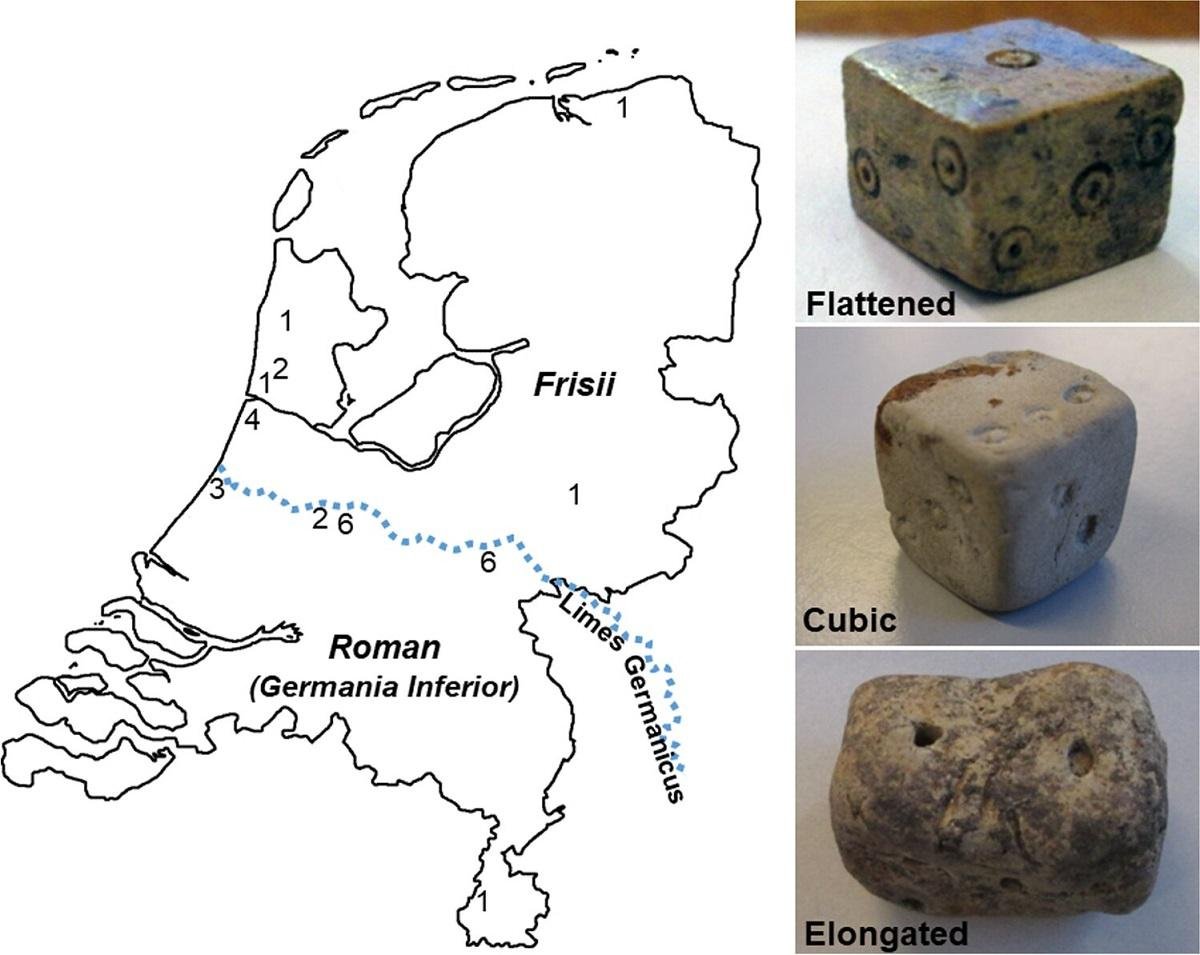

Map of modern-day Netherlands showing the location of Roman sites included in this study (number corresponds to several dice measured at each location) along with three examples of dice on right. Credit: Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s12520-022-01599-y

Map of modern-day Netherlands showing the location of Roman sites included in this study (number corresponds to several dice measured at each location) along with three examples of dice on right. Credit: Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s12520-022-01599-y

People used to play a dice-throwing game called taberna (similar to backgammon) during the Roman Empire. The dice were constructed of bone, metal, or clay and contained symbols on the faces to represent numbers, similar to modern dice. However, their shapes were markedly different.

The Roman dice were usually elongated or formed into other odd shapes that made them asymmetrical.

The researchers studied 28 die from the period in this new study and found that 24 of them were asymmetrical. They discovered a pattern in the irregularity: the icons for one and six were frequently present on larger opposing surfaces.

Previous research has shown that die asymmetry can affect the probability of a given side landing face up. The researchers predicted that the difference in size would change the odds of rolling a certain number from one in six to one in 2.4 on average. The researchers ran an experiment in order to determine whether the Romans created their dice asymmetrical in order to cheat. They invited 23 students to place markings on reproductions of the asymmetrical Roman dice.

The researchers reasoned that because the students would be unaware of the experiment’s purpose and would have no incentive to cheat, they would mostly place the marks at random. However, this was not the case, the students still placed the one and six on the larger sides. When asked why, many said it was easier because starting on a large side meant ending on a large side where they would need to lay the most pips—a result that implies the Romans were not trying to cheat, but rather to simplify their lives.

It also implies that they were unconcerned about which face received which number because they believed that many random events, like as dice throwing, were governed by fates. However, the researchers point out that more clever people would have worked out over time that certain die-throws were more likely to wind up a one or a six, and would choose one or the other.

More information: Jelmer W. Eerkens et al, Why are Roman-period dice asymmetrical? An experimental and quanтιтative approach, Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2022). DOI: 10.1007/s12520-022-01599-y