The use of fire can reveal a great deal about human evolution. Archaeologist Femke Reidsma has developed a more accurate technique for determining how our ancestors used fire. Existing archaeological investigations must be updated. Reidsma’s study was published on November 2nd in Nature Scientific Reports.

Reidsma studying a piece of bone in the lab. Credit: Leiden University

Reidsma studying a piece of bone in the lab. Credit: Leiden University

By studying heated bone and other remains in the soil, archaeologists can learn a lot about how our ancestors used fire. And fire use provides insight into a whole host of steps within human evolution, including cooking, keeping warm, hunting, and influencing the landscape around us, as well as the development of language and culture.

Reidsma wondered whether the techniques archaeologists use to say something about fire use were reliable. ‘I wanted to know whether we are drawing the right conclusions when remains – heated bones in this case – have been under certain conditions in the ground.’

The answer proved to be no, Reidsma discovered after experiments in the lab. She heated bones in various ways, both with and without oxygen. From her previous research, she already knew that this makes a difference to a bone’s composition and therefore to what can happen to it in the ground.

Reidsma studied the effect of three pH values (acid, alkaline, and neutral) on heated bones for the publication in Scientific Reports because the soil can have different chemical compositions and hence different pH values. This resulted in a toolkit comprising a reference dataset and a collection of analytical techniques that provide a more accurate picture of what has happened to heated bones in the soil.

Archaeologists will be able to use the toolkit at any site, regardless of age or location, to determine whether the absence of traces of fire is because no fire was used or because no remains of fire have been preserved. “This will tell us more about human evolution,” says Reidsma. The toolkit will also enable archaeologists to correct for the effect of soil and interpret the use of fire more accurately if heated bone has survived.

Reidsma believes that some existing archaeological studies may need to be revised as a basis of her research. For example, studies that aim to ascertain which early hominins could use fire based on the presence and absence of heated material. “Until now, we had no data on the effect of soil conditions on the material, so that was not taken into account in previous studies.”

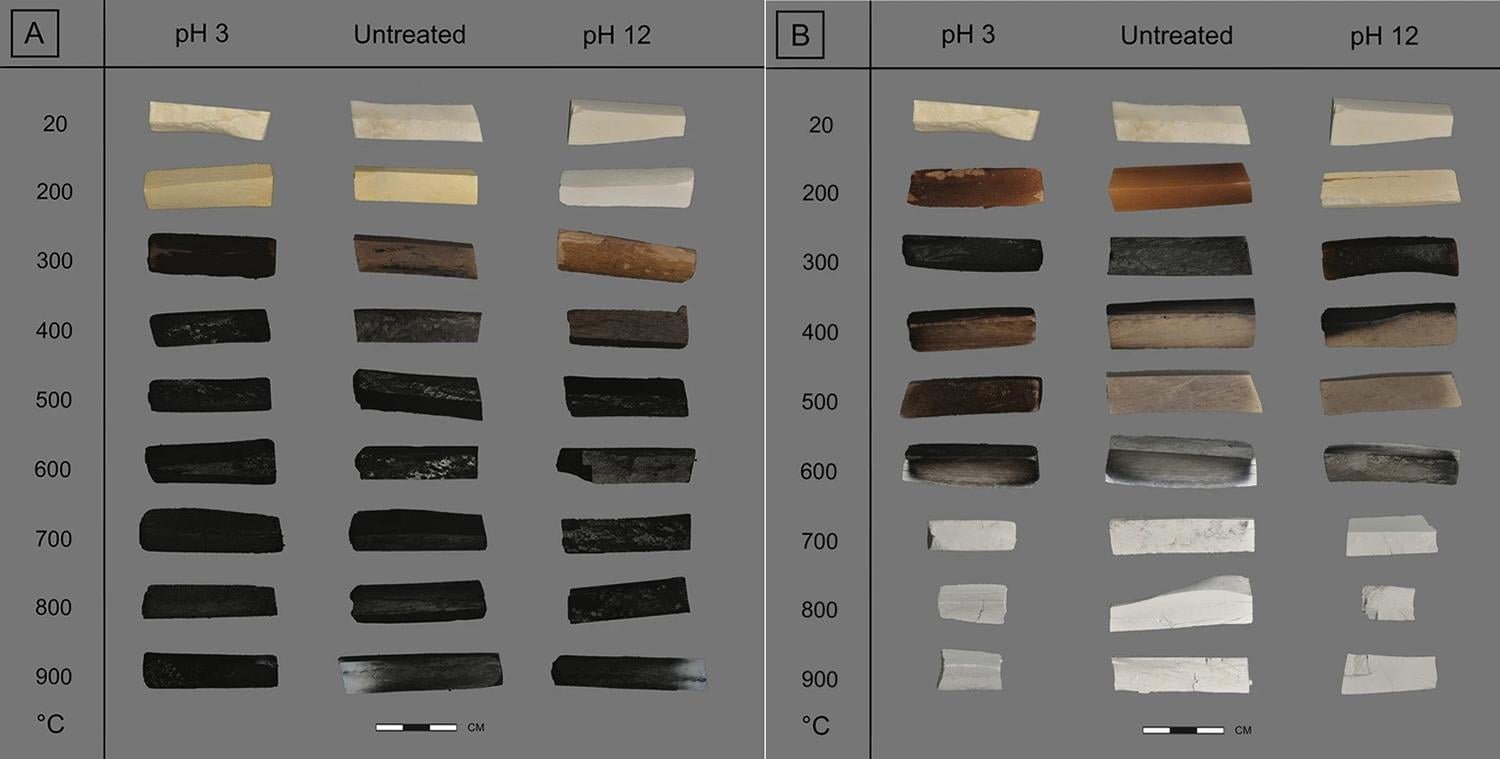

Overview of the variation in color for charred (A) and combusted (B) bone exposed to pH 3 and pH 12 conditions. Credit: Scientific Reports (2022).

Overview of the variation in color for charred (A) and combusted (B) bone exposed to pH 3 and pH 12 conditions. Credit: Scientific Reports (2022).

The new toolbox is not only useful for archaeologists, but it is also useful for anyone who works with bones found in the ground. Forensics experts, for example, who are investigating a fire.

“The effect of soil on remains is also relevant to their work,” says Reidsma. “I therefore hope that the publication in Scientific Reports will allow a wide scientific audience to read about my research.” — Leiden University

More information: Femke H. Reidsma, Laboratory-based experimental research into the effect of diagenesis on heated bone: implications and improved tools for the characterisation of ancient fire, Scientific Reports (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-022-21622-5