According to a study published in the journal Antiquity, prehistoric cooking may have been more complex than previously thought.

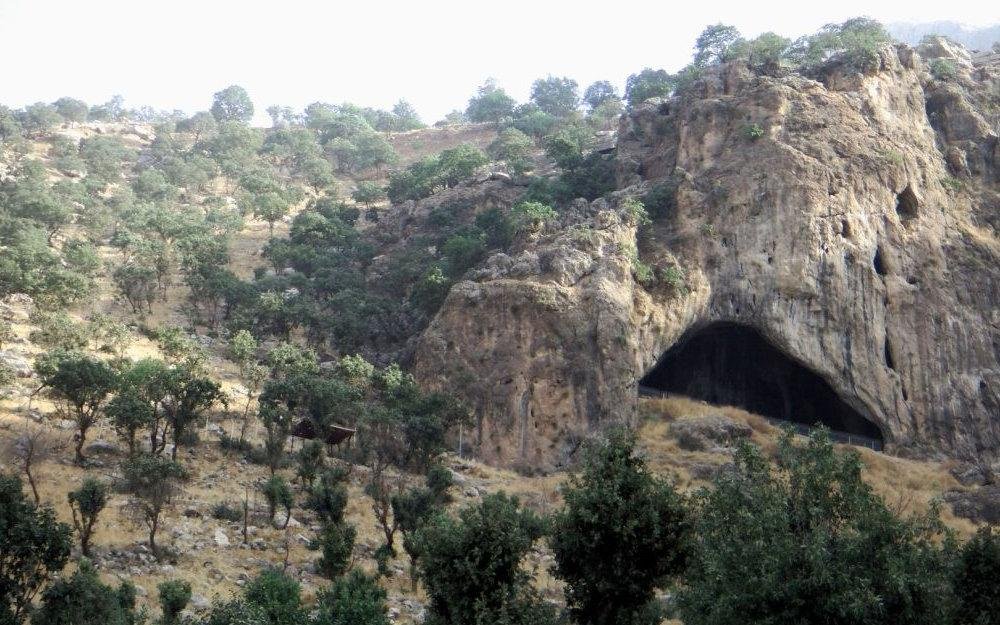

A view of the Shanidar Cave in Iraq’s Zagros Mountains. Credit: Chris Hunt

A view of the Shanidar Cave in Iraq’s Zagros Mountains. Credit: Chris Hunt

Analysis of some of the earliest charred food remains at two locations—the Shanidar Cave in Iraq’s Zagros Mountains and the Franchthi Cave in Greece—has revealed that Stone Age cooks were surprisingly sophisticated, combining an array of ingredients and using different techniques to prepare and flavor their meals.

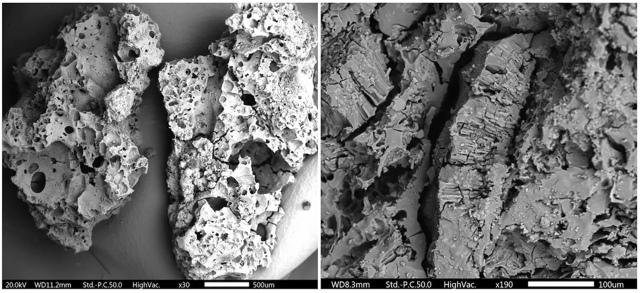

Using a scanning electron microscope, the scientists examined the carbonized plant materials discovered in the caves. This enabled them to identify the types of food plants and know how they were modified before being cooked and consumed.

Researchers discovered similar plants and culinary activities at both archaeological sites, suggesting a shared food culture. They discovered evidence of cooking that included a variety of ingredients, processes, and deliberate decisions.

Wild nuts, peas, vetch, a legume with edible seed pods, and grᴀsses were often combined with pulses such as beans or lentils, the most commonly identified ingredient, and at times, wild mustard.

To make the plants more palatable, pulses, which have a naturally bitter taste, were soaked, coarsely powdered, or pounded with stones to remove their husk.

This level of culinary complexity in Paleolithic hunter-gatherers has never been documented previously.

According to Dr Ceren Kabukcu, of the University of Liverpool, who carried out the analysis, a typical dish would probably have contained a pounded pulp of pulses, nuts and grᴀss seeds, bound together with water and flavoured with bitter tannins from the seed coats of pulses such as beans or peas, and the sharp taste of wild mustard.

Scanning Electron Microscope images of carbonized food remains. Left: The bread-like food found in Franchthi Cave. Right: Pulse-rich food fragment from Shanidar Cave with wild pea. Credit: Ceren Kabukcu/ Antiquity

Scanning Electron Microscope images of carbonized food remains. Left: The bread-like food found in Franchthi Cave. Right: Pulse-rich food fragment from Shanidar Cave with wild pea. Credit: Ceren Kabukcu/ Antiquity

The soaking and pounding of the pulse seeds at the Neanderthal cave in Iraq 70,000 years ago is the oldest evidence of food processing activity known anywhere in the world outside of Africa, Dr. Kabukcu confirmed.

“Our findings are the first real indication of complex cooking—and thus of food culture—among Neanderthals,” study co-author, Chris Hunt, an expert in cultural paleoecology at Liverpool John Moores University, told the Guardian’s Linda Geddes.

“Because the Neanderthals had no pots, we presume that they soaked their seeds in a fold of an animal skin,” he explained.

More information: Kabukcu, C., Hunt, C., Hill, E., Pomeroy, E., Reynolds, T., Barker, G., & Asouti, E. (2022). Cooking in caves: Palaeolithic carbonised plant food remains from Franchthi and Shanidar. Antiquity, 1-17. doi:10.15184/aqy.2022.143