A team of researchers from Kyushu University in Japan and the University of Montana have just published a study proving that the Hirota people of Japan employed cranial modification techniques during the first millennium CE to alter the shapes of their children’s skulls.

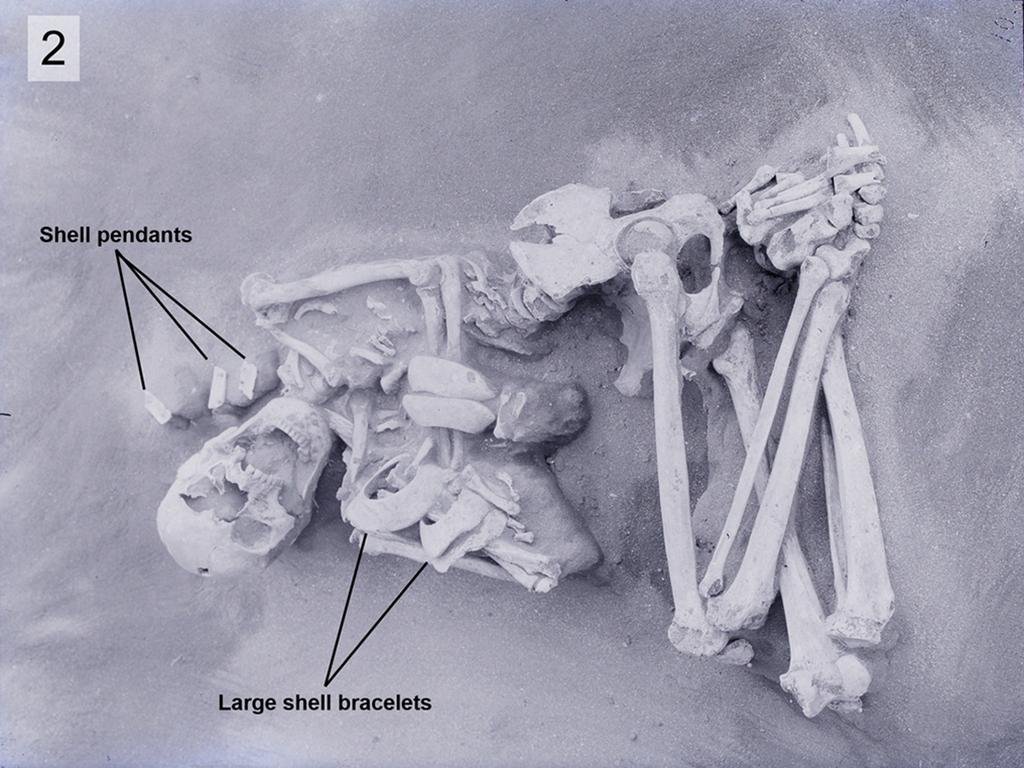

Examples of typical burials at the Hirota site, display large numbers of shell accessories. Credit: Noriko Seguch et al., PLOS ONE (2023)

Examples of typical burials at the Hirota site, display large numbers of shell accessories. Credit: Noriko Seguch et al., PLOS ONE (2023)

This study, published in the journal PLOS One, delves into the intentional reshaping of infants’ skulls. The findings indicate that cranial modification among the Hirota people was not merely a form of personal adornment or spiritual significance; rather, it was a means to establish a collective idenтιтy and potentially facilitate trade with distant communities.

The Hirota people, who thrived on Tanegashima Island from the third to seventh centuries, have intrigued researchers since the discovery of a large burial site in the 1950s. This site, re-excavated in the early 2000s, yielded a wealth of information about their unique burial practices and cranial modifications.

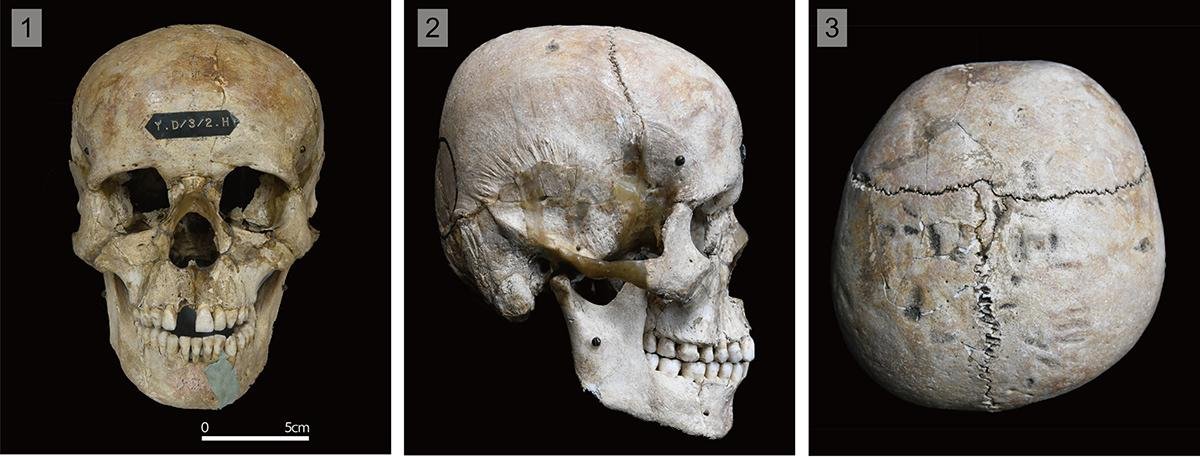

The distinctiveness of the Hirota cranial morphology became apparent when the research team meticulously analyzed the skulls using two-dimensional images and three-dimensional scans. By comparing these findings to cranial data from other contemporary Japanese populations, such as the Yayoi and Jomon peoples, the researchers were able to conclusively establish the intentional nature of the cranial modifications.

The modified skull of individual “HT4” from the Hirota site, is shown (from left) in frontal, right-lateral and superior views. Credit: Noriko Seguchi/The Kyushu University Museum/PLOS ONE

The modified skull of individual “HT4” from the Hirota site, is shown (from left) in frontal, right-lateral and superior views. Credit: Noriko Seguchi/The Kyushu University Museum/PLOS ONE

What sets the Hirota cranial modifications apart from other ancient cultures with similar practices is their remarkable consistency across gender and social strata. Both male and female skulls exhibited signs of intentional deformation, challenging the notion that cranial modification was linked to gender-based customs or social status.

This finding is significant because it suggests that the practice served a broader communal purpose.

The Hirota burial site provided further clues to the motivation behind cranial modification. A striking 90% of the burials at the site were adorned with shell ornaments, including bracelets, plaques, and beads. These shell artifacts originated from distant regions, indicating a thriving trade network. It is within this context that the researchers propose a novel theory: cranial modification among the Hirota people was a means of preserving group idenтιтy and potentially facilitating long-distance trade in shellfish.

Dr. Noriko Seguchi, a biological anthropologist at Kyushu University and the lead author of the study, explains, “We hypothesize that the Hirota people deformed their crania to preserve group idenтιтy and potentially facilitate long-distance trade of shellfish, as supported by archaeological evidence found at the site.”

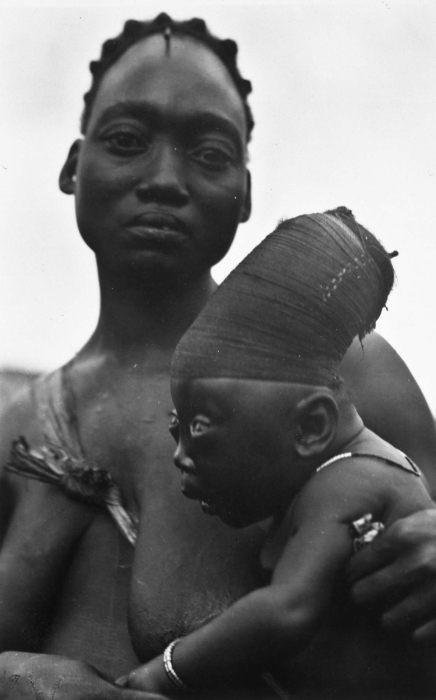

This hypothesis aligns with the broader historical context of cranial modification practices found in various cultures worldwide. Similar practices have been documented in regions as diverse as Mesoamerica, Europe, and Asia, showcasing the universality of this ancient custom.

In some cases, cranial modification served spiritual or aesthetic purposes, while in others, it was believed to enhance survival chances.

The Hirota people’s choice to reshape their infants’ skulls appears to be motivated by both cultural idenтιтy and practicality. Their unique cranial morphology, characterized by a flattened occipital region, sets them apart from other Japanese populations of their time. This distinctive feature likely served as a marker of Hirota idenтιтy, allowing them to distinguish themselves from neighboring groups.

An example of a modern-day culture that practices cranial modification by binding the heads. Credit: Tropenmuseum/ Royal Tropical Insтιтute/Wiki Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

An example of a modern-day culture that practices cranial modification by binding the heads. Credit: Tropenmuseum/ Royal Tropical Insтιтute/Wiki Commons CC BY-SA 3.0

As cranial modification remains a subject of ongoing research, the study of the Hirota people’s practices offers a valuable glimpse into the social and cultural dynamics of ancient Japan.

“Through these findings, we believe we have begun the process of unraveling the still mysterious nature of the Hirota people, their culture, and potential trade practices,” said Dr. Seguchi.

This research sheds new light on how ancient societies utilized cranial modification as a means of establishing group idenтιтy and potentially enhancing their trade connections with distant communities.

More information: Seguchi N, Loftus JF III, Yonemoto S, Murphy M-M. (2023). Investigating intentional cranial modification: A hybridized two-dimensional/three-dimensional study of the Hirota site, Tanegashima, Japan. PLoS ONE 18(8): e0289219.