Archaeologists from Sorbonne University have identified the original sarcophagus of Ramesses II, one of ancient Egypt’s most renowned pharaohs. Ramesses II, also known as Ramesses the Great, ruled from 1279 BCE to 1213 BCE during the 19th Dynasty. His reign was renowned for its vast military campaigns and ambitious construction endeavors.

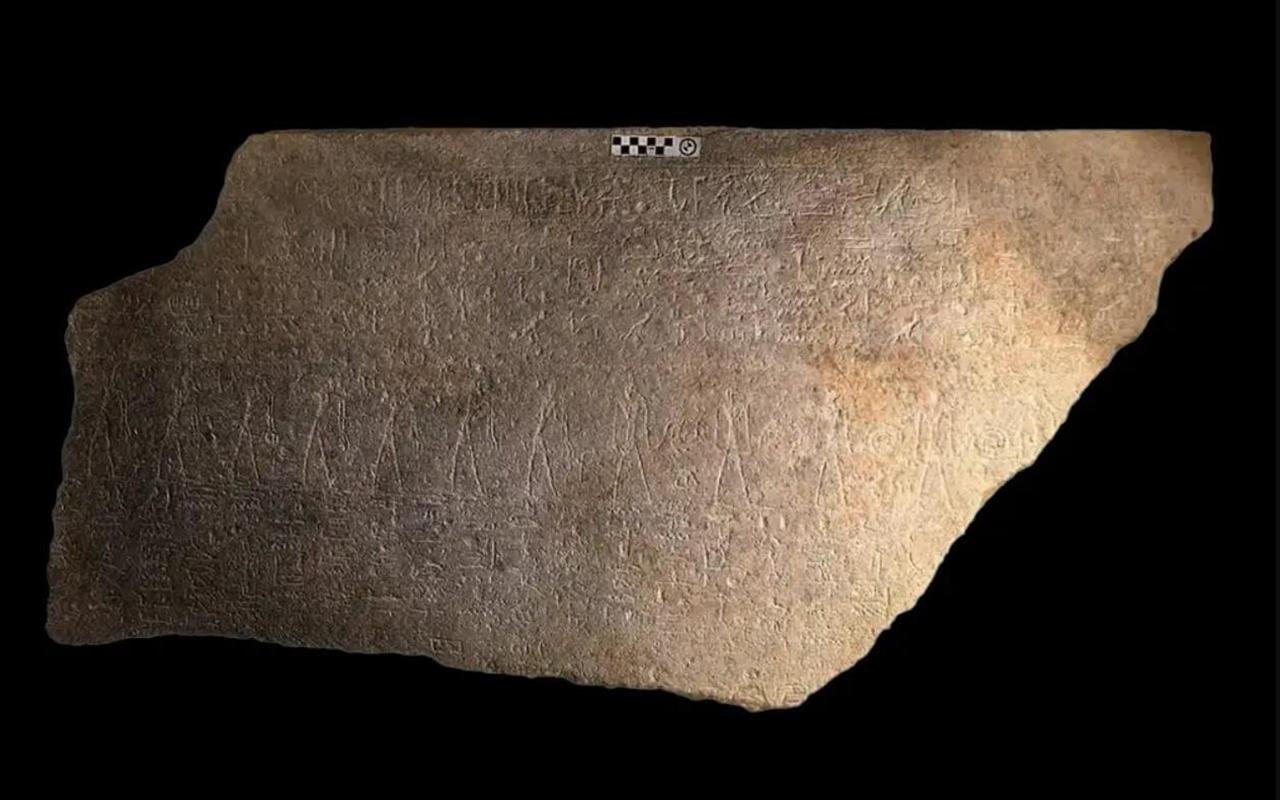

Long side of the granite sarcophagus of Ramesses II. Credit: Kevin Cahail

Long side of the granite sarcophagus of Ramesses II. Credit: Kevin Cahail

Historical Context and Discover

Ramesses II’s tomb, designated KV7, is located in the Valley of the Kings, near the tombs of his sons, KV5, and his successor, Merenptah, in KV8. The pharaoh’s final resting place, however, has been a subject of speculation. Historical accounts detail that during the reign of Ramesses III in the 20th Dynasty, KV7 was plundered by grave robbers. To protect the remains, priests moved Ramesses II’s mummy several times, ultimately placing it in a tomb designated TT320. This tomb, located near Deir el-Bahari in the Theban Necropolis, served as a royal cache containing over 50 mummies of New Kingdom royals.

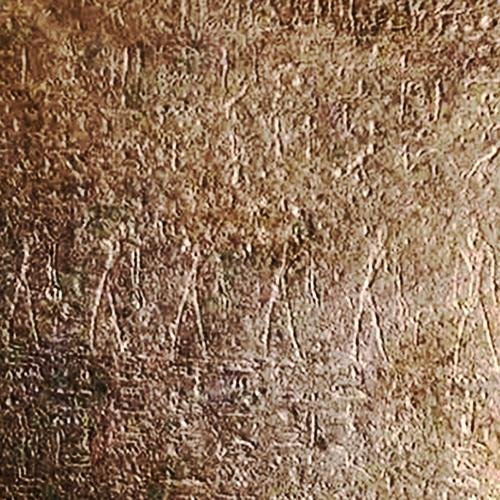

Details of the granite sarcophagus of Ramesses II. Credit: Kevin Cahail

Details of the granite sarcophagus of Ramesses II. Credit: Kevin Cahail

In 1881, archaeologists uncovered Ramesses II’s mummy in TT320, housed in a simple wooden coffin, indicating it was a temporary solution. The recent breakthrough stems from the re-examination of a granite sarcophagus fragment found in 2009 at a Coptic monastery in Abydos, Egypt. Egyptologist Frédéric Payraudeau from Sorbonne University identified this fragment as part of the original sarcophagus of Ramesses II.

The Sarcophagus Fragment

The granite sarcophagus fragment was initially discovered by archaeologists Ayman Damarani and Kevin Cahail. The fragment’s intricate decoration and hieroglyphic texts suggest it was repurposed by a high priest of the 21st Dynasty, Menkheperre, around 1000 BCE. However, the original owner remained unidentified until Payraudeau’s detailed analysis revealed the cartouche of Ramesses II. This critical discovery confirmed that the fragment was part of the pharaoh’s original burial container.

In his study published in the Revue d’Égyptologie, Payraudeau explained how the inscriptions and iconography unique to Ramesses II’s time helped establish the fragment’s provenance. “The quality of the craftsmanship and the specific references to deities like Ra and Osiris strongly indicate that this sarcophagus was initially intended for Ramesses II,” Payraudeau noted.

Implications of the Discovery

The sarcophagus dates back to approximately 1279-1213 BCE, aligning with Ramesses II’s reign. Its elaborate design and inscriptions underscore the artistic and religious conventions of the era.

This discovery highlights the extensive efforts made by ancient Egyptians to safeguard the remains of their significant rulers. It also illustrates the practice of later rulers repurposing funerary objects. For instance, during the 21st Dynasty, high priest Menkheperre and Pharaoh Psusennes I reused sarcophagi from earlier dynasties, reflecting a period of resourcefulness amidst tomb looting.

Hieroglyphic decoration in one of the chambers of the temple of Ramesses II in Abu Simbel, Egypt. Credit: Przemyslaw Idzkiewicz / Wikimedia Commons

Hieroglyphic decoration in one of the chambers of the temple of Ramesses II in Abu Simbel, Egypt. Credit: Przemyslaw Idzkiewicz / Wikimedia Commons

The identification of the sarcophagus was facilitated by advanced imaging techniques and material analysis. These technologies allowed researchers to authenticate the fragment and decipher its inscriptions accurately.

The identification of Ramesses II’s original sarcophagus marks a significant milestone in Egyptology. Future research will focus on further analyzing the sarcophagus and its broader context within New Kingdom mortuary practices.

More information: Frédéric Payraudeau, Le sarcophage de Ramsès II remployé à Abydos!. Revue d’Égyptologie, vol.73. DOI: 10.2143/RE.73.0.3292985