Maritime archaeologists from Bournemouth University have uncovered and studied a 13th-century shipwreck off the coast of Dorset in southern England, offering rare insights into the medieval trade networks that were crucial in constructing some of England’s most iconic religious monuments.

The three grave slabs observed on the wreck from the pH๏τogrammetry of the site (scales are 1m). Credit: Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

The three grave slabs observed on the wreck from the pH๏τogrammetry of the site (scales are 1m). Credit: Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

The ship, now known as the Mortar Wreck, was carrying a valuable cargo of Purbeck stone, a type of limestone quarried from the Isle of Purbeck, renowned for its ability to be polished to a marble-like finish.

The 13th century in England, a period marked by relative peace, economic stability, and burgeoning construction projects, saw the construction of grand religious structures like Salisbury Cathedral and Westminster Abbey.

These projects required vast amounts of building materials, and the transportation of these materials relied heavily on the extensive trade networks that connected quarries, workshops, and construction sites across the country. Despite the significance of these networks, much about them remains unknown due to the scarce archaeological evidence available from this period.

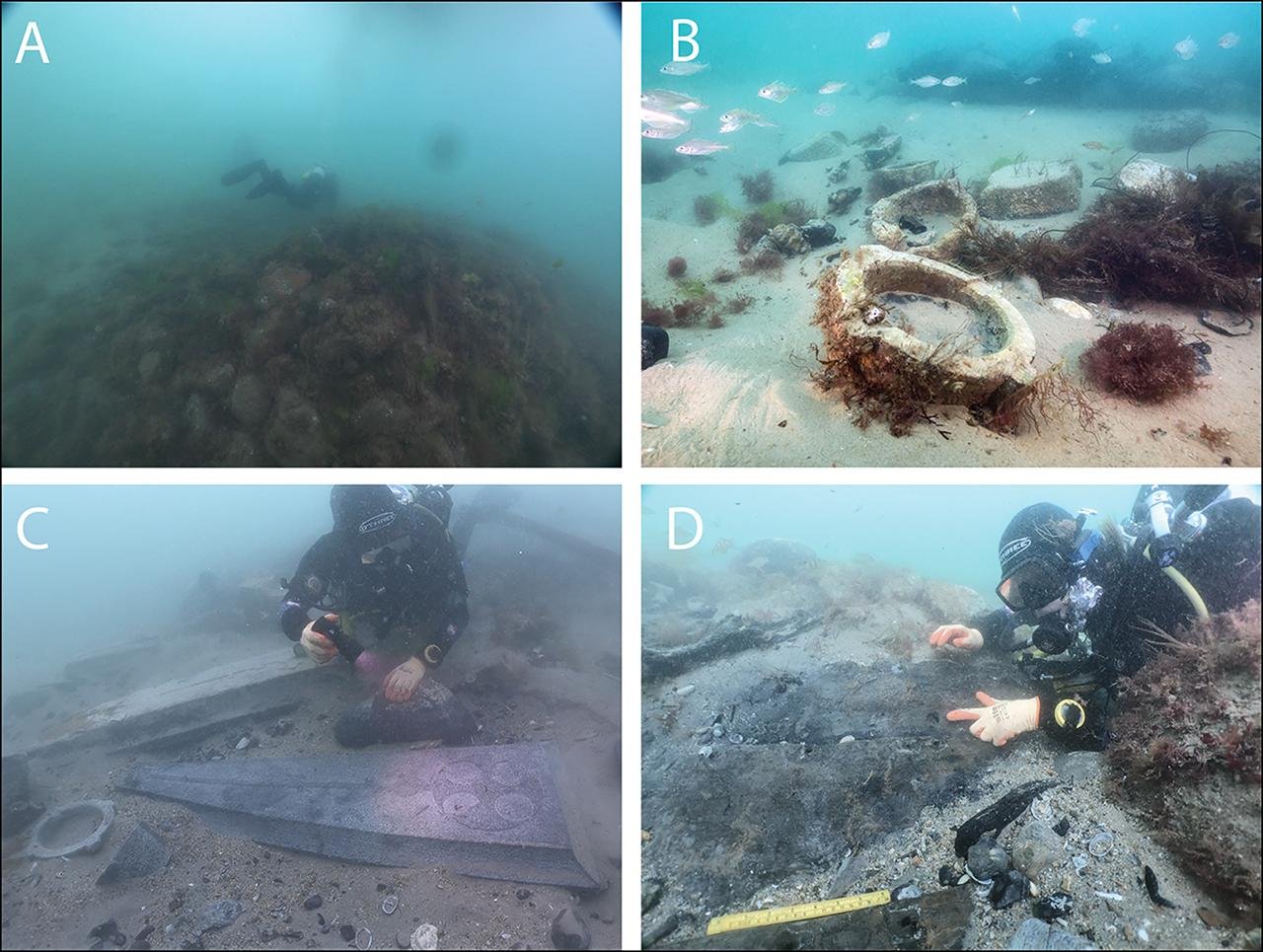

The wreck site on the seabed: A) the stone mound; B) mortars; C) grave slabs; D) articulated hull timbers. Credit: Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

The wreck site on the seabed: A) the stone mound; B) mortars; C) grave slabs; D) articulated hull timbers. Credit: Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

Tom Cousins, a researcher at Bournemouth University and lead author of the study published in the journal Antiquity, said: “Thousands of tons of cargo were shipped daily around the shores and rivers of England during this period,” he said. “Although wrecks and shipping losses were common, very little archaeological evidence of the ships and trade networks survives.”

The Mortar Wreck, identified as a significant historical find only in 2019 and designated as a historic wreck in 2022, is one of the few surviving pieces of evidence.

The ship, dating back to around 1250 CE, was carrying Purbeck marble, a prized material used extensively in the construction and decoration of ecclesiastical buildings throughout England and beyond. The marble, with its distinctive dark hue and polished finish, was in high demand for crafting ornamental objects such as grave slabs, architectural moldings, and flooring.

The cauldron (left), posnet (upper right) and brazier (lower right) recovered from the wreck. Credit: Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

The cauldron (left), posnet (upper right) and brazier (lower right) recovered from the wreck. Credit: Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

The discovery of unfinished grave slabs among the wreck’s cargo suggests that the ship was likely en route to a major construction site or a specialized workshop in London, where the final polishing would have taken place. This points to the existence of complex, multi-stage trading networks that were essential in the distribution and processing of such materials.

The ship’s journey from Poole Harbour, laden with high-status goods from local quarries, underscores the economic importance of maritime transport during this period. Water transport was a crucial component of the medieval economy, with ships carrying heavy goods like stone much more cheaply and efficiently than land transport. The stone trade, in particular, played a vital role in the economy, with the cost of transporting the stone often rivaling the price of the stone itself.

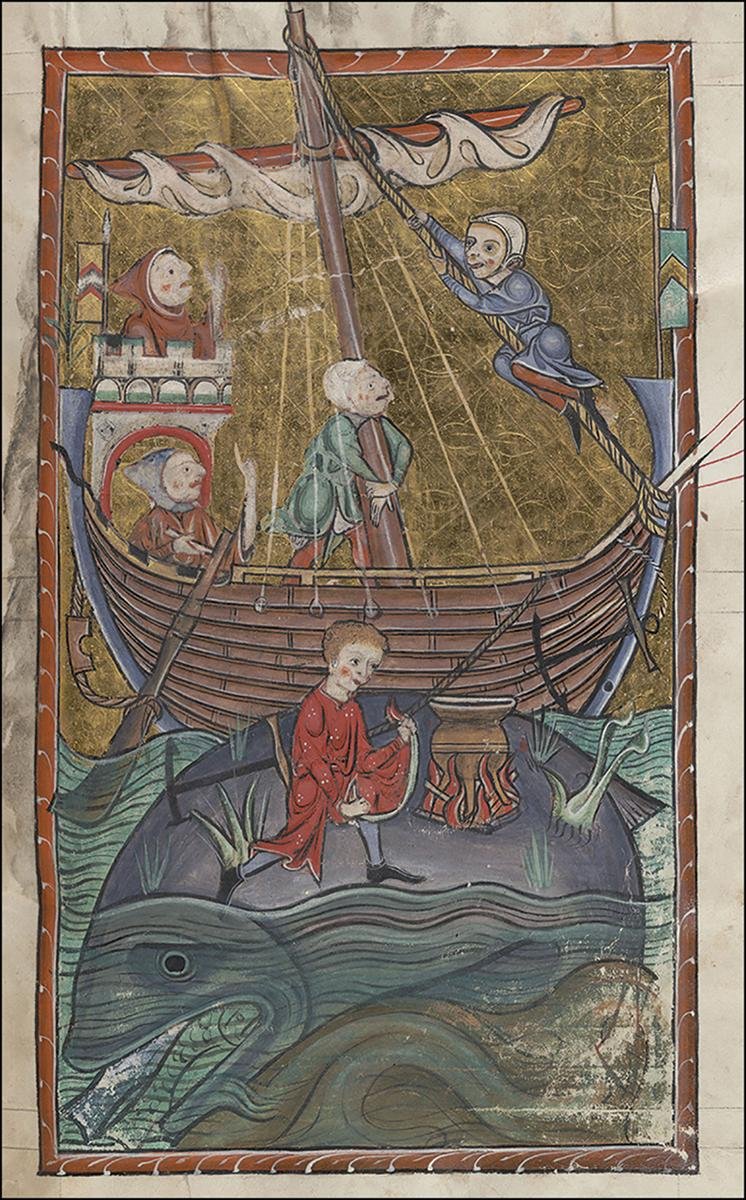

An illustration from a thirteenth-century bestiary depicting a typical merchant ship. Credit: Bodleian Library 2018 / Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

An illustration from a thirteenth-century bestiary depicting a typical merchant ship. Credit: Bodleian Library 2018 / Cousins T., Antiquity (2024)

The Mortar Wreck offers a unique archaeological site that encapsulates daily life, trade, and technology in the 13th century. It provides rare evidence of the logistics of medieval shipping, including the sourcing, transportation, and working of building materials that were critical to England’s architectural heritage.

Cousins noted that while the loss of the ship would have been devastating at the time, today it presents a valuable opportunity to explore a key period in European history. “By studying the remains of the Mortar Wreck, we can learn more about technology and trade in the thirteenth century, as well as the activities of sailors and traders, their lives and environment,” he concluded.

More information: Cousins T. (2024). The Mortar Wreck: a mid-thirteenth-century ship, wrecked off Studland Bay, Dorset, carrying a cargo of Purbeck stone. Antiquity: 1-15. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.82