New discoveries at Château des Milandes in Castelnaud-la-Chapelle, Dordogne, France, have revealed embalming practices in early modern Europe, historically ᴀssociated with cultures like ancient Egypt or South America. The Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW) has confirmed the embalming of seven adults, five children, and an elderly woman, all members of the aristocratic Caumont family, who lived during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Skull of the individually buried woman, which was sawn into pieces to remove the brain. Credit: M. Bessou/CNRS UMR

Skull of the individually buried woman, which was sawn into pieces to remove the brain. Credit: M. Bessou/CNRS UMR

The Caumont family, prominent figures of their time, practiced embalming as a deeply rooted tradition to emphasize their elevated social status. This technique appears to have been primarily for ceremonial purposes, allowing bodies to be displayed during elaborate funeral rituals rather than for long-term preservation. Caroline Partiot, a researcher at the Austrian Archaeological Insтιтute of ÖAW, explained, “The application of embalming to family members, regardless of age at death and gender, also reflects the acquisition of status through birth.”

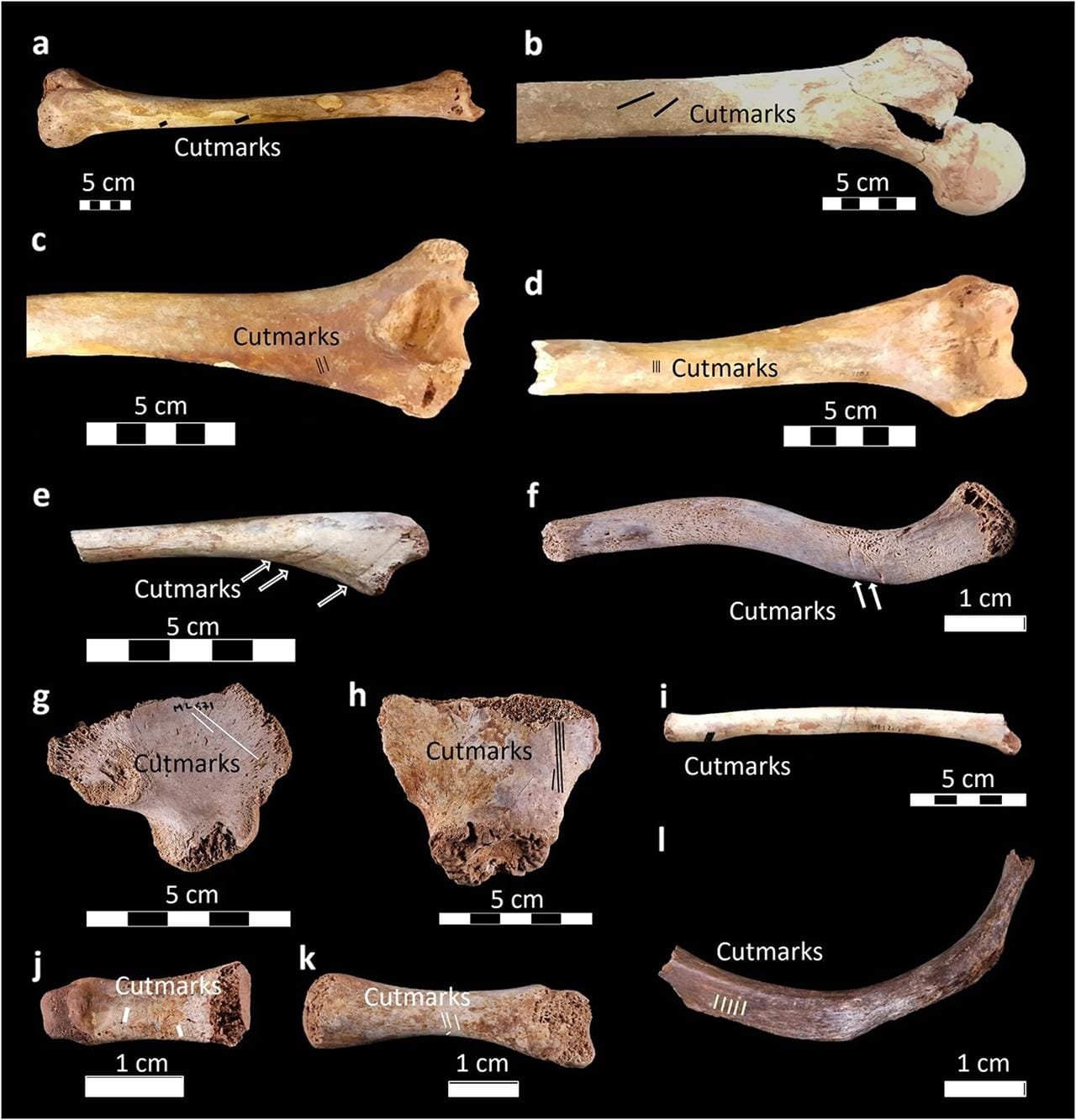

The findings included detailed examinations of the embalmed remains. Researchers reconstructed a nearly complete skeleton from scattered fragments and identified precise cut marks on bones, indicating a highly standardized process. Partiot noted, “Our examinations of a complete individual and nearly 2,000 fragments show careful and highly standardized technical treatment of the deceased, similar for both adults and children. This reflects knowledge that had been pᴀssed down over two centuries.”

The process involved complete skinning of the body, including limbs, fingertips, and toes. Internal organs, including the brain, were removed, and the cavities were filled with balsamic and aromatic substances to delay decomposition. These methods align closely with those described by Pierre Dionis, a leading French surgeon of the early 18th century, who documented such techniques during an autopsy in Marseille in 1708.

Individual burial ML2021 In situ. Credit: H. Gaillard / C. Partiot et al., Sci Rep (2024), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Individual burial ML2021 In situ. Credit: H. Gaillard / C. Partiot et al., Sci Rep (2024), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

The practice of embalming multiple members of the same family, including children, is uncommon in Europe’s archaeological record. Previously, only the Medici family in 15th-century Italy demonstrated similar traditions. The Caumont family crypt represents the first bioarchaeological evidence of embalming applied equally to adults and infants.

The Château des Milandes crypt, first uncovered in 2017, housed scattered skeletal remains of the family, while a subsequent 2021 excavation revealed the grave of an elderly woman buried separately. These discoveries highlight the longevity of the embalming tradition within the Caumont lineage, persisting for at least two centuries. Partiot emphasized, “It is remarkable that this tradition lasted for at least two centuries.”

A selection of embalming marks on adult and immature postcranial bones. Credit: C. Partiot et al., Sci Rep (2024), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

A selection of embalming marks on adult and immature postcranial bones. Credit: C. Partiot et al., Sci Rep (2024), CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

Published in Nature, the study underscores the ceremonial role of embalming in early modern France. Unlike the long-term preservation goals of Egyptian mummification, European embalming aimed to manage decomposition temporarily, facilitating transportation and public display of the deceased.

The Château des Milandes itself, constructed by François de Caumont in the late 15th century, later gained fame as the residence of Josephine Baker from 1947 to 1968. Today, it continues to captivate with its storied past and unique contributions to our understanding of European history.

ÖAW

More information: Partiot C, Bessou M, Kacki S, Penet M, Sachau-Carcel G, Castex D. (2024). First bioarchaeological evidence of the familial practice of embalming of infant and adult relatives in Early Modern France. Sci Rep.14;14(1):27075. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-78258-w