The Alexander Mosaic, a remarkable find from Pompeii’s ruins, continues to captivate historians, art lovers, and scholars. Archaeologists discovered it in 1831 in the luxurious House of the Faun.

The Alexander Mosaic (detail), From House of the Faun, Pompeii. Public domain

The Alexander Mosaic (detail), From House of the Faun, Pompeii. Public domain

This Roman masterpiece depicts the key Battle of Issus (333 BCE), where Alexander the Great led his Macedonian army to defeat the Persian ruler Darius III. Measuring approximately 12 x 17 feet (5.82 x 3.13 meters) and composed of nearly 2 million tesserae, the mosaic is now housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (MANN).

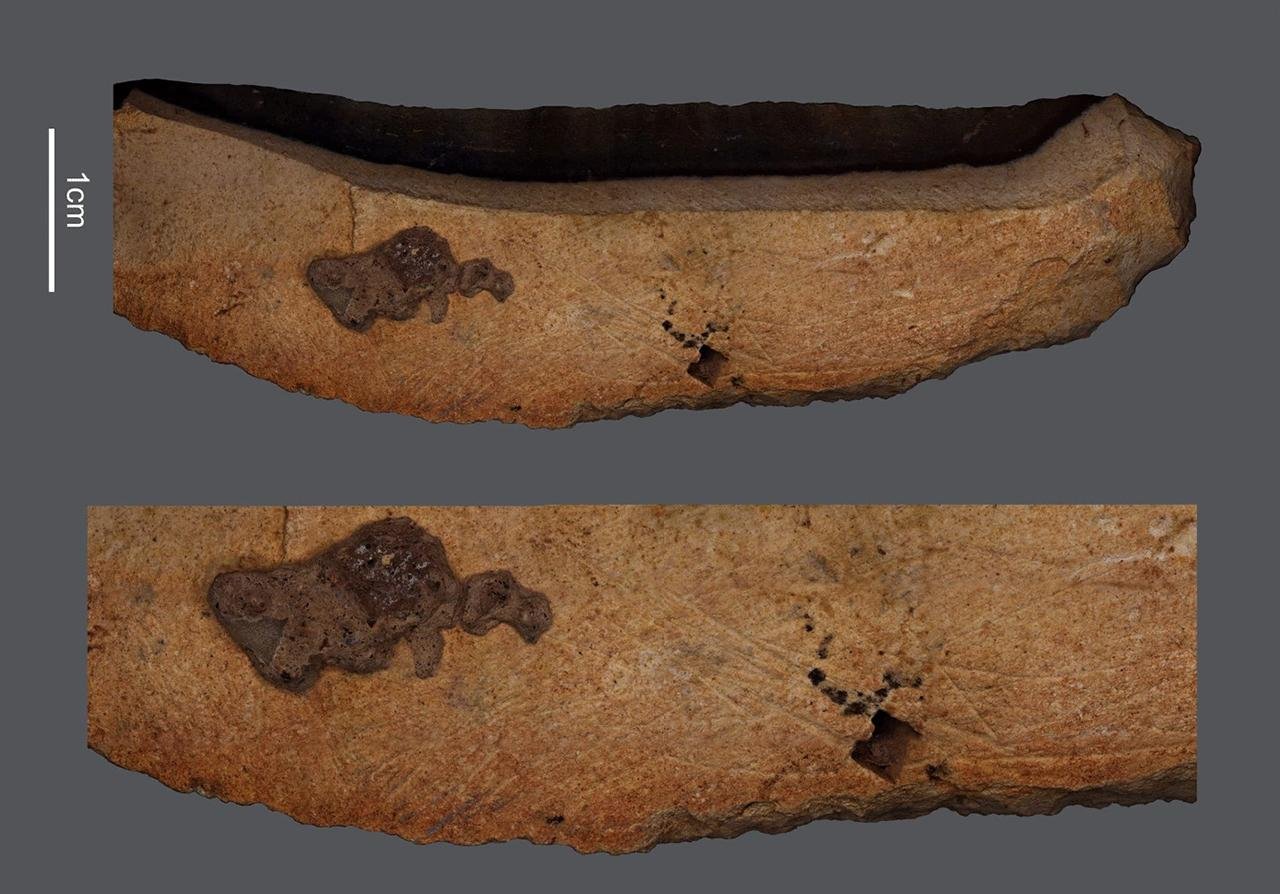

The Battle of Issus was a defining moment in Alexander’s campaign that showcased his strategic genius against a much larger Persian force. Scholars believe this mosaic is a Roman copy of the lost Hellenistic painting created by Philoxenus of Eretria, dating to about 315 BCE. Its minute details in opus vermiculatum feature tiny tesserae, less than 4 millimeters wide each, which create a dynamic and vivid portrayal of war. The artwork captures Alexander’s piercing gaze as he charges forward, spear in hand, while Darius III’s charioteer attempts a hasty retreat.

Recent research in PLOS ONE investigated the mosaic’s composition and revealed its diverse origins. The research group analyzed the tesserae using non-invasive techniques, including portable X-ray fluorescence (pXRF), Raman spectroscopy, and infrared thermography. These analyses identified ten different colors, composed of materials sourced from across the Roman Empire, including Italy (Carrara marble), Greece (serpentinites), and the Iberian Peninsula (basalt). Some tesserae were traced even to quarries in Tunisia, testifying to the immense effort invested in this monumental work.

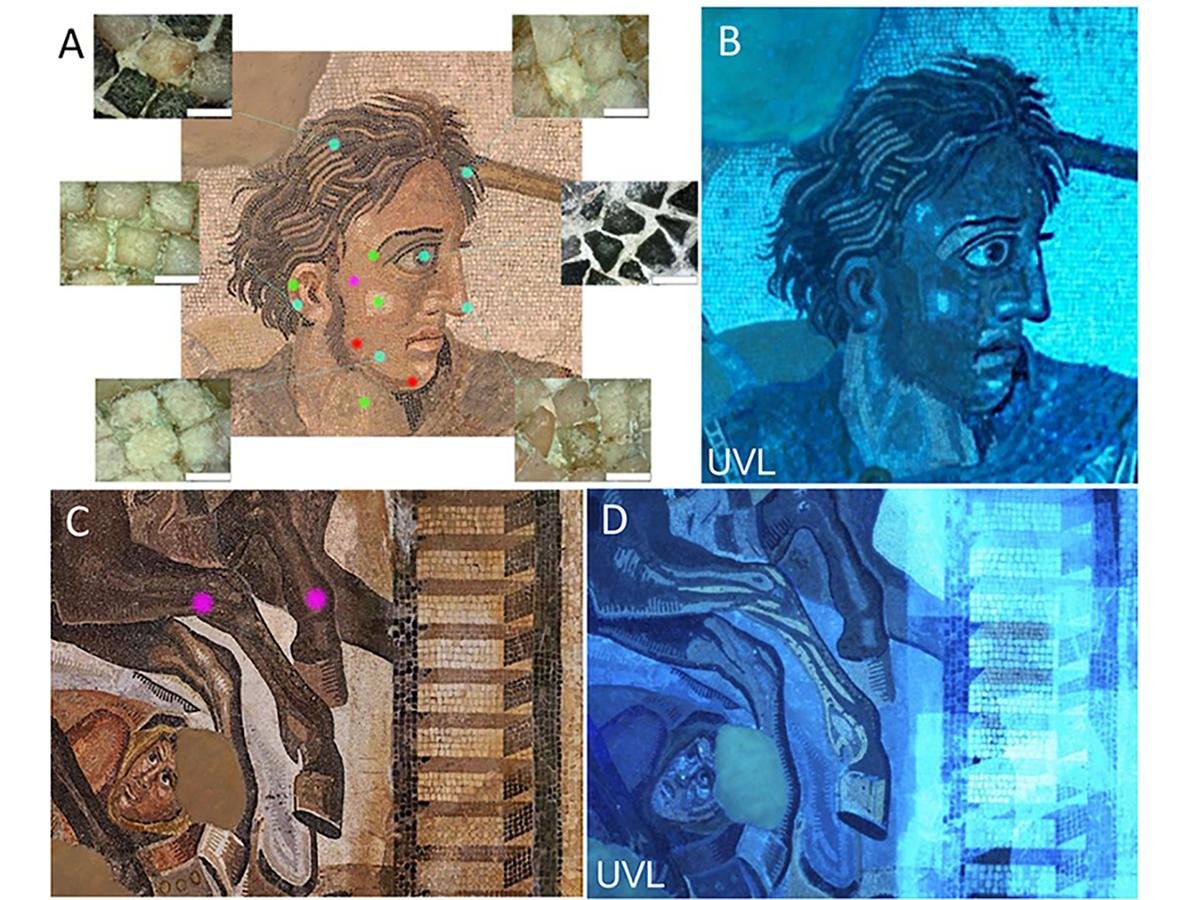

Estimation of external treatments placement by multispectral imaging, with examples of interpolation of multi-technique study. Credit: G. Balᴀssone et al., PLoS ONE (2025)

Estimation of external treatments placement by multispectral imaging, with examples of interpolation of multi-technique study. Credit: G. Balᴀssone et al., PLoS ONE (2025)

Since the discovery of the Alexander Mosaic, it has faced challenges related to its preservation and past restoration efforts. Gypsum and wax layers were applied to consolidate the structure during its movement to MANN in 1843. These repairs, although offering temporary protection, have contributed to surface degradation through various chemical and environmental processes. Multispectral imaging and endoscopic investigations of the mosaic’s underside document voids and adhesive residues from early reattachment attempts, highlighting zones of structural weakness. Thermal imaging has also revealed further deformations and instability in the mortars, raising serious concerns for ongoing conservation.

The mosaic’s artists were true masters of detail, especially in rendering Alexander’s face. Variations in luminescence within certain pink tesserae are doubtless due to differences in chemical composition. These subtleties enhance the lifelike quality of the work, making it one of the most memorable renderings of Alexander in ancient art.

The Alexander Mosaic in the Archaeological Museum of Naples. Credit: ho visto nina volare / Wikimedia Commons

The Alexander Mosaic in the Archaeological Museum of Naples. Credit: ho visto nina volare / Wikimedia Commons

The Alexander Mosaic remains one of the most important connections to Roman craftsmanship and the legacy of Alexander the Great. Current restoration projects led by MANN in cooperation with the University of Naples Federico II not only protect the integrity of the mosaic but also expand our knowledge of the time of its creation and historical background.

More information: Balᴀssone G, Cappelletti P, De Bonis A, De Simone A, Di Martire D, Graziano SF, et al. (2025) From tiny to immense: Geological spotlight on the Alexander Mosaic (National Archaeological Museum of Naples, Italy) using non-invasive in situ analyses. PLoS ONE 20(1): e0315188. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0315188