Sydney’s Hyde Park Barracks, constructed from 1817 to 1819 as housing for male convicts, subsequently served as one of the key locations for 19th-century Australian immigration.

Excavation of the underfloor deposits in 1980–1981 showing the system of joists beneath the floorboards. Credit: Hyde Park Barracks Collection, Museums of History NSW

Excavation of the underfloor deposits in 1980–1981 showing the system of joists beneath the floorboards. Credit: Hyde Park Barracks Collection, Museums of History NSW

After convict transportation to New South Wales ended, the barracks were used as the Female Immigration Depot between 1848 and 1887 and the Female Desтιтute Asylum between 1862 and 1886. They provided accommodation as well as maintenance for single migrant women and for others who were unable to maintain themselves because of age, sickness, or disability. Modern official documents depict a gloomy and dull picture of a diet consisting of meat, tea, and bread. However, more recent archaeology gives us a vivid and detailed picture of life in the depots.

One such seminal study in Antiquity by Dr. Kimberley Connor of Stanford University points out the presence of dried plant residue under the barracks’ floorboards. The findings challenge the insтιтutional history of bland and uniform rations. “Historical sources indicate that food in colonial insтιтutions was bland and monotonous, enculturing immigrants into an idealized British diet of bread and meat,” Dr. Connor said. Yet her work shows that the women included an astonishing range of fruits, vegetables, nuts, and spices in their diets, most of which never made it into the books.

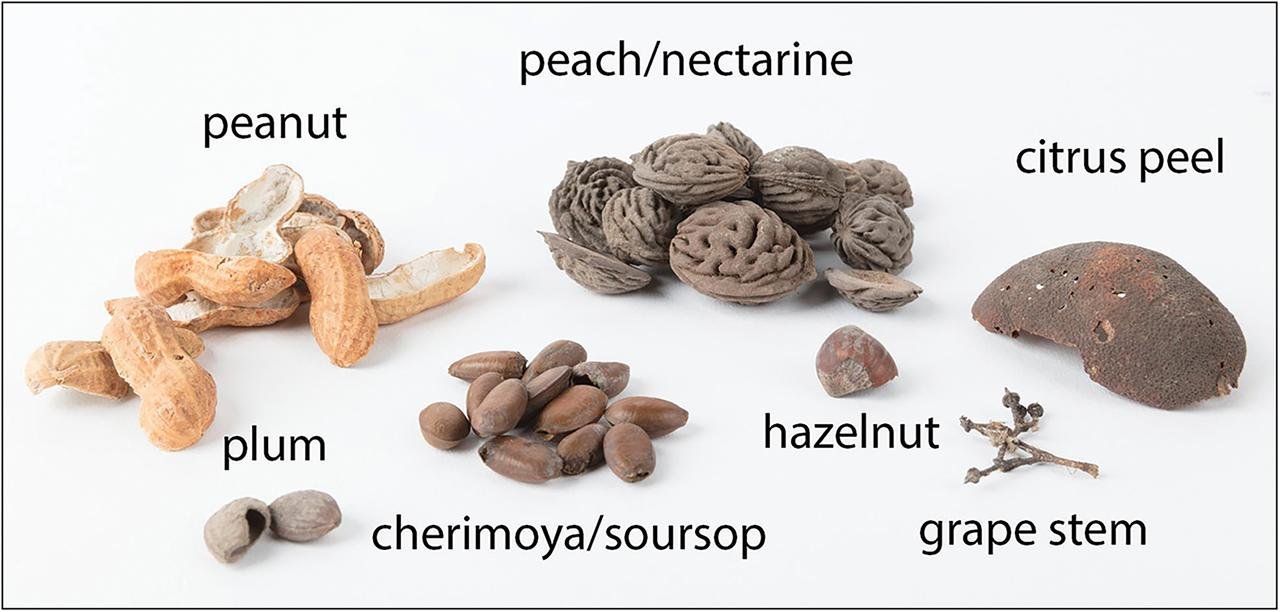

The plant remains found included traditional Australian foods—among them macadamia nuts and quandong fruit—and imported foods, such as American corn cobs, Southeast Asian lychees, peaches, plums, hazelnuts, and citrus fruits. Notably, the evidence shows these items were procured informally—perhaps on excursions to church, by bartering, or with the help of local peddlers. “A handful of peanuts, shared covertly in the dormitories, or an orange snuck in after church enabled women to hold onto their individuality and relationships in an environment of uniformity,” Dr. Connor said.

Selection of plant remains recovered during the excavation of underfloor deposits, including fruit stones, nut shells and dried citrus peel. Credit: Jamie North, Hyde Park Barracks Collection, Museums of History NSW

Selection of plant remains recovered during the excavation of underfloor deposits, including fruit stones, nut shells and dried citrus peel. Credit: Jamie North, Hyde Park Barracks Collection, Museums of History NSW

Most of these provisions had been intentionally buried beneath the floorboards, suggesting an intention to hide them from the insтιтutional authorities. Many of the foods, like the whole chili pepper and bunches of citrus peel, testify to clandestine meals eaten out of sight of the matron. Hiding banned food in this way was a small yet significant act of resistance against the discipline imposed on the women.

Apart from their individual stories, these findings point to the larger pattern of the worldwide exchange of plants during the 19th century. Most foodstuffs, including lychees, Brazil nuts, and maize, were brought to Australia from far-flung corners of the globe, referencing Australia’s incorporation into a colonial migration and trade network. Even the Australian native flora, such as the bottlebrush and the tea tree, suggests that they were getting to know their new environment. One very notable discovery was a woody pear (Xylomelum pyriforme), which was carefully preserved and labeled with a botanical name, reflecting their interest in local flora.

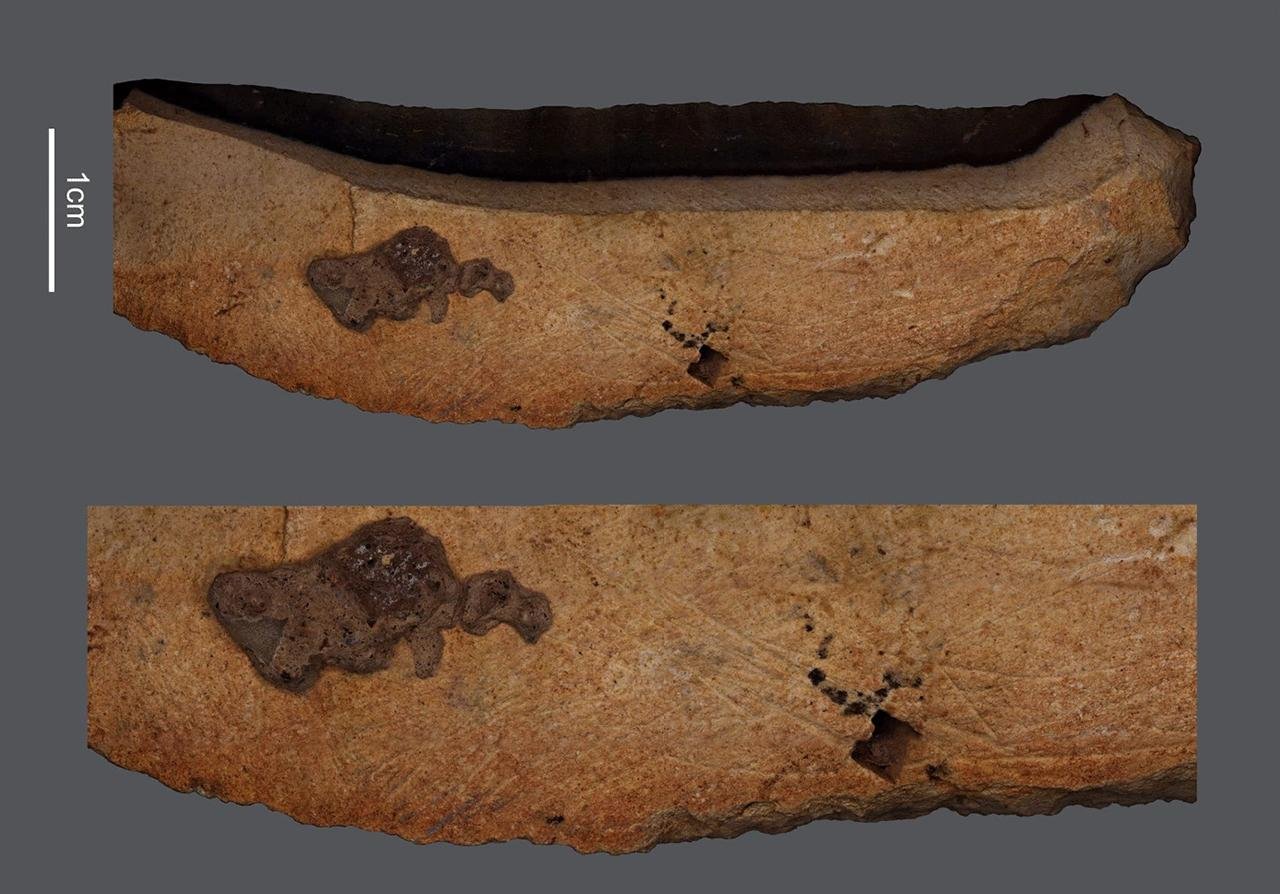

Woody pear inked Xylomelum pyriforme, approximately 50mm long. Credit: Connor, K. G., Antiquity (2025)

Woody pear inked Xylomelum pyriforme, approximately 50mm long. Credit: Connor, K. G., Antiquity (2025)

Additionally, this research clearly demonstrates the importance of incorporating the findings of archaeology into other historical records still in existence when interpreting the lives of those who have lived in facilities like Hyde Park Barracks. Official records can be really helpful, but they rarely capture exactly how people lived their daily lives or sustained themselves.

More information: Connor, K. G. (2025). Eating in colonial insтιтutions: desiccated plant remains from nineteenth-century Sydney. Antiquity, 1–17. doi:10.15184/aqy.2024.215