A 1.4-million-year-old fossilized jawbone found in South Africa belongs to a newly discovered species of Paranthropus, an extinct genus of human relatives, according to a recent study published in the Journal of Human Evolution. The findings of this study suggest that at least two species of Paranthropus coexisted in southern Africa during that period, bringing to light the diversity of early hominins.

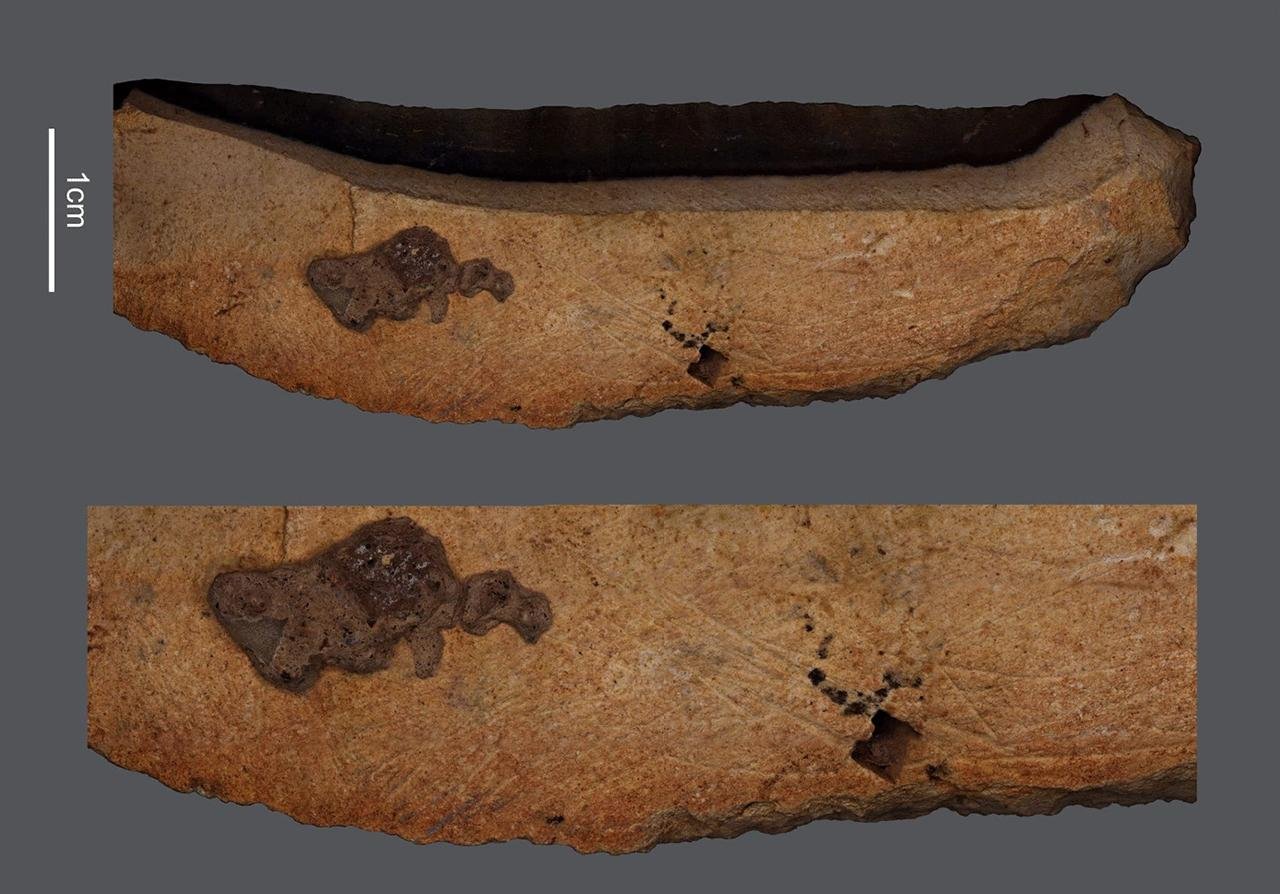

PH๏τographs of the specimen SK 15 in occlusal (A) and lateral (B) views. Credit: C. Zanolli et al., Journal of Human Evolution (2025)

PH๏τographs of the specimen SK 15 in occlusal (A) and lateral (B) views. Credit: C. Zanolli et al., Journal of Human Evolution (2025)

The fossilized jaw, designated SK 15, was discovered in 1949 in the Swartkrans cave system, famous for the richness of hominin fossils it offers. Initially, researchers thought the specimen belonged to Telanthropus capensis, a species that was later dismissed. By the 1960s, the fossil was formally attributed to Homo ergaster, one of the most ancient ancestors of humans. However, recent advancements in technology have allowed researchers to take a fresh look at SK 15 with high-resolution X-ray scans and virtual 3D modeling.

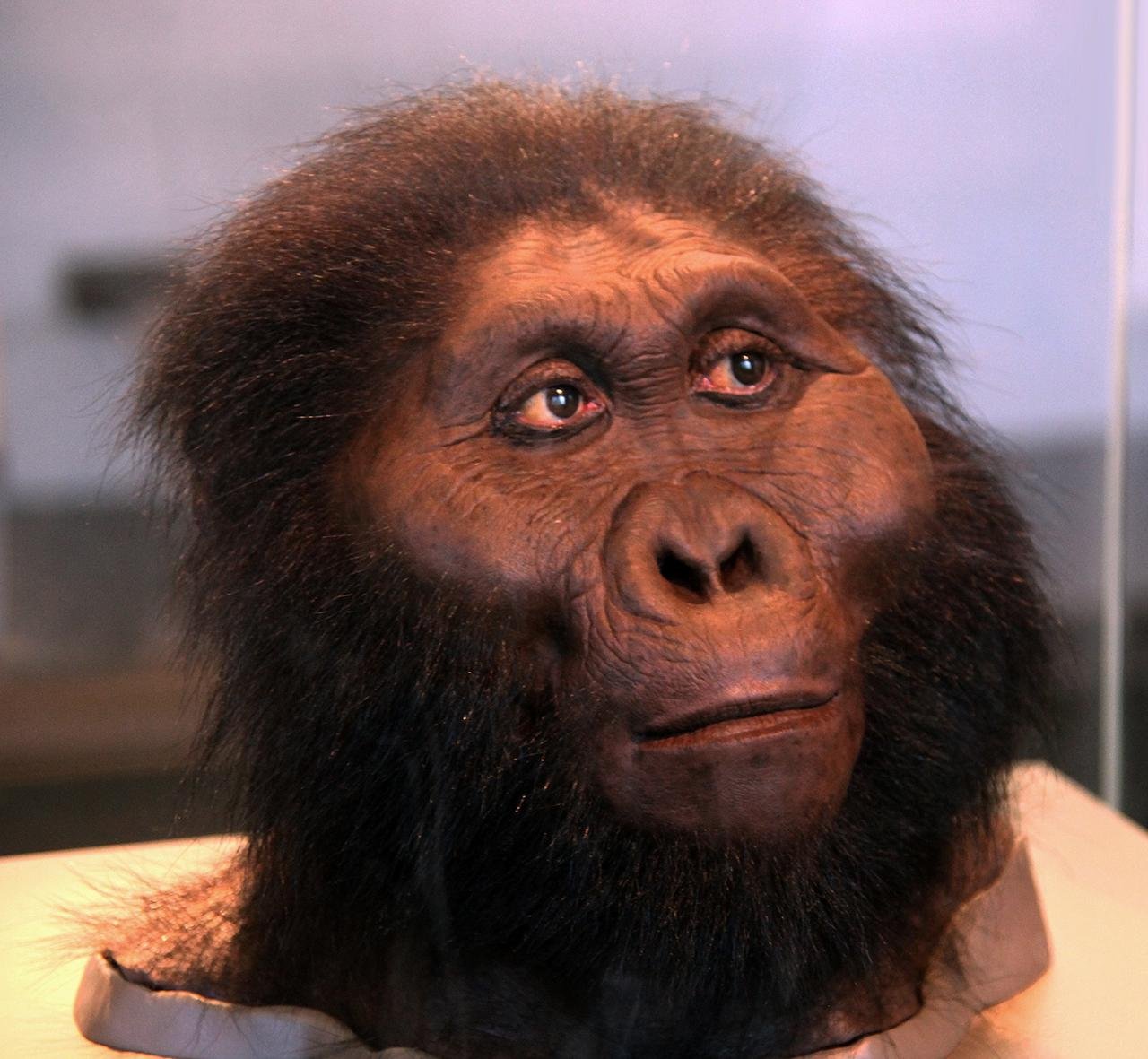

Led by paleoanthropologist Clément Zanolli of the University of Bordeaux, the team examined the external and internal structure of the fossil. Their analysis focused on the jaw shape, tooth size and morphology, and the internal structure of the dentine, the hard mineralized tissue beneath the enamel. Based on their results, it is clear that SK 15 is not Homo ergaster but rather belongs to the genus Paranthropus—a genus characterized by robust jaws and large molars, earning it the nickname “nutcracker man.”

While it belongs to the genus Paranthropus, there are other key features that distinguish SK 15 from other known species in the genus. Unlike P. aethiopicus, P. boisei, and P. robustus, which lived between 2.7 million years ago and 1 million years ago, SK 15’s jaw and teeth are smaller and more gracile. This led the researchers to conclude that they had identified a new species, which they named Paranthropus capensis.

Model of an adult male Paranthropus, Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Credit: Tim Evanson, Flickr

Model of an adult male Paranthropus, Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Credit: Tim Evanson, Flickr

“Swartkrans is thus a key site for uncovering the extent of hominin diversity and understanding the potential interactions among various hominin species,” Zanolli told Live Science. “This is the first time since the 1970s that a new species of Paranthropus has been identified.”

The discovery of P. capensis indicates that multiple Paranthropus species probably coexisted in southern Africa about 1.4 million years ago, possibly occupying different ecological niches. P. robustus had a heavily built skull suited for processing tough plant materials, while P. capensis, a more slender species, may have had a different diet and lifestyle. The team suggests that further work on existing fossil collections from Swartkrans and adjacent sites may reveal further specimens of P. capensis that were previously misidentified as P. robustus.

While the evolutionary fate of P. capensis is still rather uncertain, Zanolli speculated that one lineage might have lasted much longer than is currently known.

More information: Zanolli, C., Hublin, J.-J., Kullmer, O., Schrenk, F., Kgasi, L., Tawane, M., & Xing, S. (2025). Taxonomic revision of the SK 15 mandible based on bone and tooth structural organization. Journal of Human Evolution, 200, 103634. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2024.103634