Stephen Spielberg’s Schindler’s List is rightly celebrated for its unflinching portrayal of the Holocaust, which is based on the true story of Oskar Schindler and his Jewish workforce. Schindler was a German factory owner who initially saw the ghettoization of Kraków’s Jewish population in 1939 as a business opportunity to exploit. His real-life transformation upon witnessing the crimes perpetrated by SS soldiers against this population inspired one of Hollywood’s most powerful attempts at coming to terms with the Holocaust.

More than 30 years after its release, Schindler’s List is still the highest-grossing film about the Holocaust ever made. It’s also commonly ranked among the best Holocaust movies, not least for its authentic yet accessible depiction of one of history’s most harrowing events. The film has undoubtedly raised awareness in society at large about the horrors inflicted on Jewish people by the Nazis. However, its historical accuracy has been questioned by both historians and Holocaust survivors. As with most historical movies, Schindler’s List uses dramatic license to tell its story. To determine how accurate the movie is, it’s important to separate the facts from the fiction.

10

Gets Right: The Girl In Red

She Was A Real Person

A key moment in Schindler’s List occurs during the destruction of the Kraków Ghetto, as Nazi SS soldiers round up and murder thousands of Jewish people in the streets. From the midst of the panicstricken crowds, a young girl appears, wearing a red coat. Apart from this singular detail, the entire movie is in black-and-white. Schindler’s List director Steven Spielberg meant for the girl’s red coat to symbolize the slaughter of Europe’s innocent Jewish population happening in plain sight of the world.

Yet the character isn’t just a metaphor. Author Thomas Keneally heard about an actual little girl who wore red from members of her family who survived the Ghetto. Keneally decided to incorporate this striking detail into his historical novel Schindler’s Ark, on which Spielberg’s movie is based. Spielberg then made the girl’s red clothing the focus of his film’s inciting incident.

Today, some sources claim that the girl’s real idenтιтy was Genya Gittel Chill, who was known to wear a red cap before she was killed during the liquidation of the Kraków Ghetto (via Find a Grave). Others claim she was Roma Ligocka, a woman who was still alive in her eighties as of 2018, who recognized herself as the red-coated girl when she watched Schindler’s List (via Porta Polonica). Either way, the girl was real, and not just a cinematic device.

9

Gets Wrong: Schindler Witnessing The Destruction Of Kraków’s Jewish Ghetto

There’s No Evidence Of Him Riding Up Lasota Hill That Day

Another aspect of the scene featuring the girl in red definitely didn’t happen, though. Oskar Schindler himself didn’t witness the destruction of the Kraków Ghetto from the top of Lasota Hill. In Schindler’s List, the factory owner takes a leisurely ride up the hill on horseback with his mistress, only to encounter a horrifying spectacle of ethnic cleansing in the neighborhood down below.

According to the historian David M. Crowe, Schindler had already been made aware of the Ghetto’s impending destruction before it happened. It didn’t come as a shock to him. What’s more, there’s no evidence to support the film’s depiction of Schindler at the top of Kraków’s most famous hill on March 13th or 14th 1943, the two days on which the full liquidation of Kraków Ghetto took place (via Forbes). This detail is an example of Spielberg and screenwriter Steven Zaillian using artistic license in Schindler’s List.

8

Gets Right: Schindler’s Sub-Camp On His Factory Site

It Improved The Living Conditions Of His Workers

On the other hand, Schindler’s List is entirely accurate in showing Oskar Schindler creating a camp for his Jewish workforce on the grounds of his factory. He did so under the pretense of increasing productivity, because the long journey that the workers had to make from Płaszów concentration camp and back again every day was a waste of time and energy.

As camp survivor Rena Finder puts it, “If I got sick in Plaszów they would have killed me. If you stayed in the clinic there for more than a day, they’d shoot the patient.”

In fact, Schindler’s own camp effectively saved the lives of many of its inmates. They received proper food, were allowed to stay with their families, and weren’t at the mercy of SS guards. As camp survivor Rena Finder puts it, “If I got sick in Plaszów they would have killed me. If you stayed in the clinic there for more than a day, they’d shoot the patient.” (via Time) But in Schindler’s camp, she stayed in the clinic with pneumonia for three days, and made it out alive.

7

Gets Wrong: Schindler’s Guilt About Not Saving More People

In Reality He Made A Speech Taking Credit For Saving His Workers

Nevertheless, most of Kraków’s Jewish population didn’t survive the Holocaust. An emotional scene at the end of Schindler’s List shows the тιтle character breaking down in tears at the thought that he could have saved more people. This scene never happened, and runs contrary to all the evidence about the real Oskar Schindler’s atтιтude to his own actions (via Forbes). For the rest of his life, he made a point of emphasizing the heroic role he played in saving so many of his workers, to the extent that he took credit for the actions of others.

This atтιтude is reflected in the actual speech Schindler gave to his workers before bidding them farewell, in which he cataloged his “innumerable personal interventions” to save his workforce from “deportation and liquidation” (via Yad Vashem). The real Schindler may have been a hero by many measures, but he doesn’t seem to have been too concerned about those he didn’t manage to save.

6

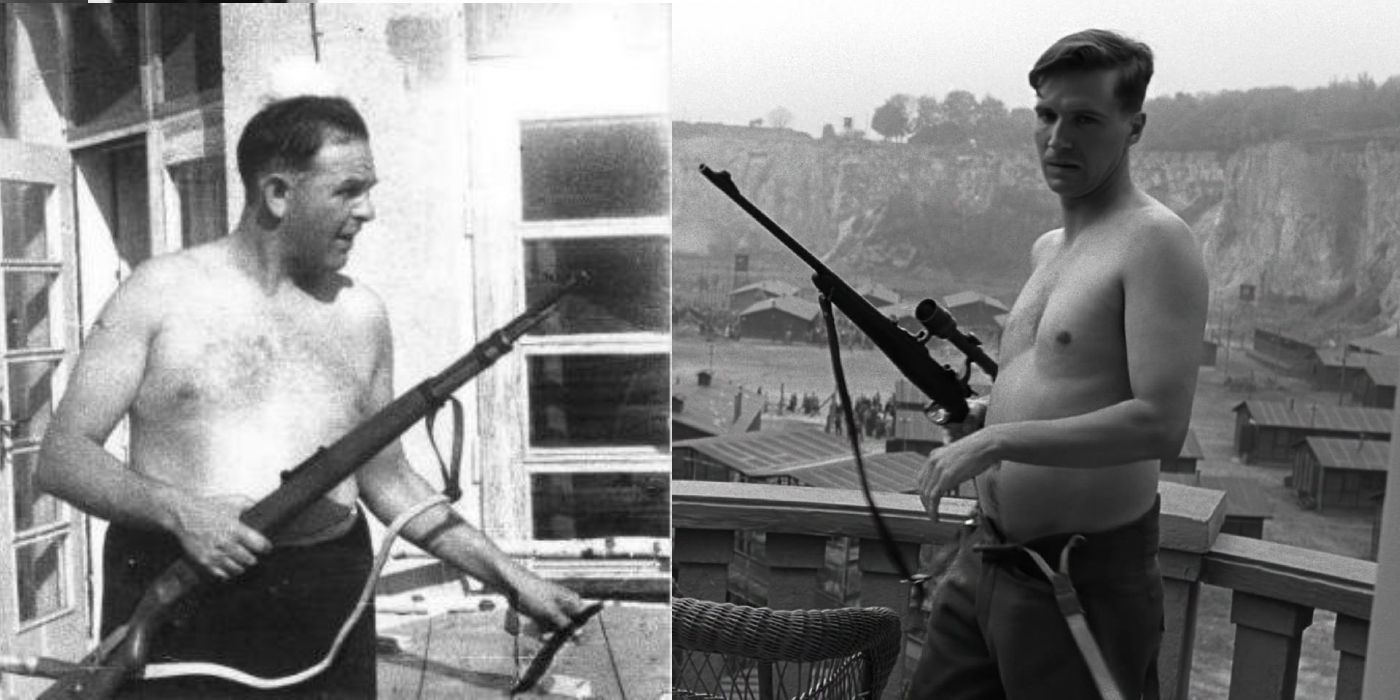

Gets Right: Amon Göth Shooting Prisoners From His Balcony

His Housemaid Recalled Him Enjoying It As a Pastime

Meanwhile, many of the appalling acts carried out by local SS officer Amon Göth, played by Ralph Fiennes in Schindler’s List, are drawn directly from reality. The real Göth was found guilty of mᴀss homicide and torture by Poland’s Supreme National Tribunal, and executed in 1946 for his actions. A scene in which he’s seen shooting Plaszów prisoners for sport from his balcony without a shirt on, is taken straight from a firsthand account by his Jewish housemaid Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig (via United States Holocaust Memorial Museum).

“You see those dumb heads?” Göth would tell Jonas-Rosenzweig. “I’m going to shoot [them].” He would shoot “like hell” according to her account, whistling a happy tune with a look of pure satisfaction spread across his face as his victims fell to the ground. If anything, Schindler’s List underplays the real Göth’s barbaric actions, as Spielberg and the movie’s producers felt that certain incidents would be too graphic to show to a mainstream audience.

5

Gets Wrong: Göth’s Attraction to His Jewish Maid

The SS Officer Was Too Anti-Semitic To Feel This Way

Still, the film does err on the side of fiction when it portrays Göth as physically attracted to another of his Jewish housemaids, Helen Hirsch. One scene shows him on the verge of Sєxually ᴀssaulting her in his basement, before he brutally beats her and crushes her with a shelf instead. While it is true that Göth kept Hirsch in his basement, together with Jonas-Rosenzweig, he never showed any attraction to either of them.

Helen Hirsch was the only one of Amon Göth’s Jewish housemaids to be depicted in Schindler’s List, with Helen Jonas-Rosenzweig not appearing as a character.

In her recollections of Göth, Jonas-Rosenzweig made it clear that she felt he was too anti-Semitic to have been attracted to a Jewish woman (via Palm Beach Post). His hatred ran so deep that she couldn’t fathom him ever desiring Hirsch on any level. Nor did she ever witness anything in his basement to suggest otherwise.

4

Gets Right: The Women On Schindler’s List Were Sent To Auschwitz-Birkenau

They Went There For “Inspection” By The SS

Once Oskar Schindler has secured the lives of part of his workforce by insisting they’re employed at his new factory in Brünnlitz, Schindler’s List shows the women on his list being diverted to Auschwitz-Birkenau instead. Auschwitz was famously the largest of the death camps built by the Nazis, and the movie suggests that these women are facing certain death, before Schindler again intervenes to save them.

It’s entirely true that the women on Schindler’s list were sent to Auschwitz-Birkenau before reaching the relative safety of his arms factory in Brünnlitz. However, they weren’t sent there to be killed. Rather, the SS insisted on “inspecting” them before letting them return to work for Schindler, to ensure they were physically capable of working (via Time). Those who were considered unfit for work could well have been murdered, but the majority seem to have pᴀssed the inspection without the need for further bribes from Schindler, unlike what the movie portrays.

3

Gets Wrong: The List Included 1,100 Names

Only 1,000 Names Were On The List Itself

A relatively minor inaccuracy of Schindler’s List confuses the number of workers Schindler himself was involved in saving the number of workers who ended up at his factory in Brünnlitz. In the film’s closing moment, Schindler’s Jewish accountant, Itzhak Stern, played by Ben Kingsley, tells him, “There are 1,100 people alive because of you.” In a sense, that number is correct, because 1098 Jewish workers were working for Schindler at the end of the war. But only 1,000 of them were saved via a list he had drawn up – 700 men and 300 women (via Time).

Oskar Schindler is now widely credited with saving a total of approximately 1,200 Jewish people from the Holocaust (via History.com).

The other 98 workers had escaped or been moved from other concentration camps, and so weren’t brought to Brünnlitz on Schindler’s initiative. By solely mentioning the number 1,100, the movie implies that there were 1,100 people on Schindler’s list. But that number is a slight overestimate.

2

Gets Right: Schindler’s Workers Wrote A Letter Recognizing His Efforts

They Hoped It Would Help Him “Establish A New Life”

The letter that the Jewish workers give their boss in Schindler’s List, “trying to explain things” to the Allied forces in case of Oskar Schindler’s capture, is a real historical document. It details the extraordinary efforts that Schindler undertook to protect and care for his workers, as well as other Jewish refugees who found their way to his factory in Brünnlitz during the final months of the war.

The last line of the letter “pleads” for Schindler to receive help in starting a new life, since he “sacrificed his entire fortune” to save his workers (via Auschwitz.dk). It’s not true, however, that every worker signed the letter, as the movie depicts. It was only signed by Stern, factory medic Dr. Hilfstein and former president of Kraków’s Zionist executive Chaim Salpeter.

1

Gets Wrong: Schindler Made The List Himself

A Jewish Overseer In Schindler’s Camp Drew Up Multiple Lists

As its тιтle suggests, Schindler’s List portrays Oskar Schindler himself drawing up a list of factory workers to be employed in his new factory in Brünnlitz, which is typed up by his accountant, Stern. In this way, he is shown as directly responsible for the fate of more than 1,000 Jewish people who survived the Holocaust because their names were on that list. This detail is arguably the most important historical inaccuracy in the movie.

Oskar Schindler didn’t draw up the list of those whose lives were saved through their continued employment at his factory. He couldn’t have done, because at the time he was in jail, being investigated for bribing a Nazi commander. Marcel Goldberg, a corrupt Jewish overseer in the camp at Schindler’s Plaszów factory, was the one responsible for choosing the inmates to include on a total of nine lists of names (via The Guardian). Amon Göth’s secretary, Mietek Pemper, who was also Jewish, then wrote the lists themselves (via The Telegraph).

Goldberg and Pemper’s roles in drawing up the lists are never clarified in Schindler’s List, as it didn’t make for the heroic climax befitting a Hollywood movie. The omission of this detail helped cement Oskar Schindler’s legacy as a savior of the Jewish people.

Sources: Find a Grave; Porta Polonica; Forbes; Time; Yad Vashem; United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Palm Beach Post; History.com; Auschwitz.dk; The Guardian; The Telegraph