Beneath the turquoise waters of northern Israel’s Gan Ha-Shelosha National Park, archaeologists have uncovered the remarkable network of a medieval tunnel system that once powered sugar mills in the Mamluk period. Carved into soft tufa rock along Nahal ‘Amal, the tunnels reveal how 14th- to 15th-century engineers transformed brackish spring water into mechanical energy—turning a finite resource into the driving force of a thriving sugar industry.

One of the Mamluk-era tunnels discovered. Credit: Azriel Yechezkel / A. Frumkin et al., Water History (2025)

One of the Mamluk-era tunnels discovered. Credit: Azriel Yechezkel / A. Frumkin et al., Water History (2025)

The discovery, led by Prof. Amos Frumkin of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was revealed during modern infrastructure work that exposed five parallel tunnel openings. Their alignment and precision suggested an engineered hydraulic system rather than natural formations. Unlike the open aqueducts typical of Roman and Byzantine times, however, these channels were carved underground—an adjustment to both the valley’s geology and the saline nature of its springs.

Radiometric uranium–thorium dating of the stalacтιтes that formed inside the tunnels shortly after excavation placed their construction in the late Mamluk era, sometime between the 14th and 15th centuries CE. This was the height of sugar production across the eastern Mediterranean, when the fertile Bet She’an Valley was one of the major regions where sugarcane was cultivated and processed.

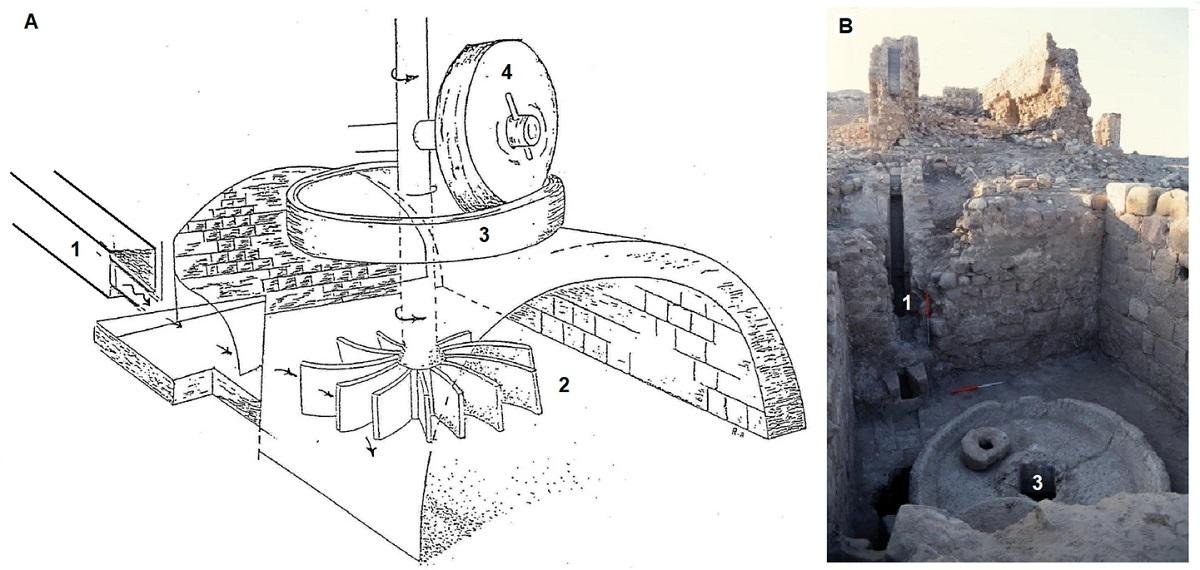

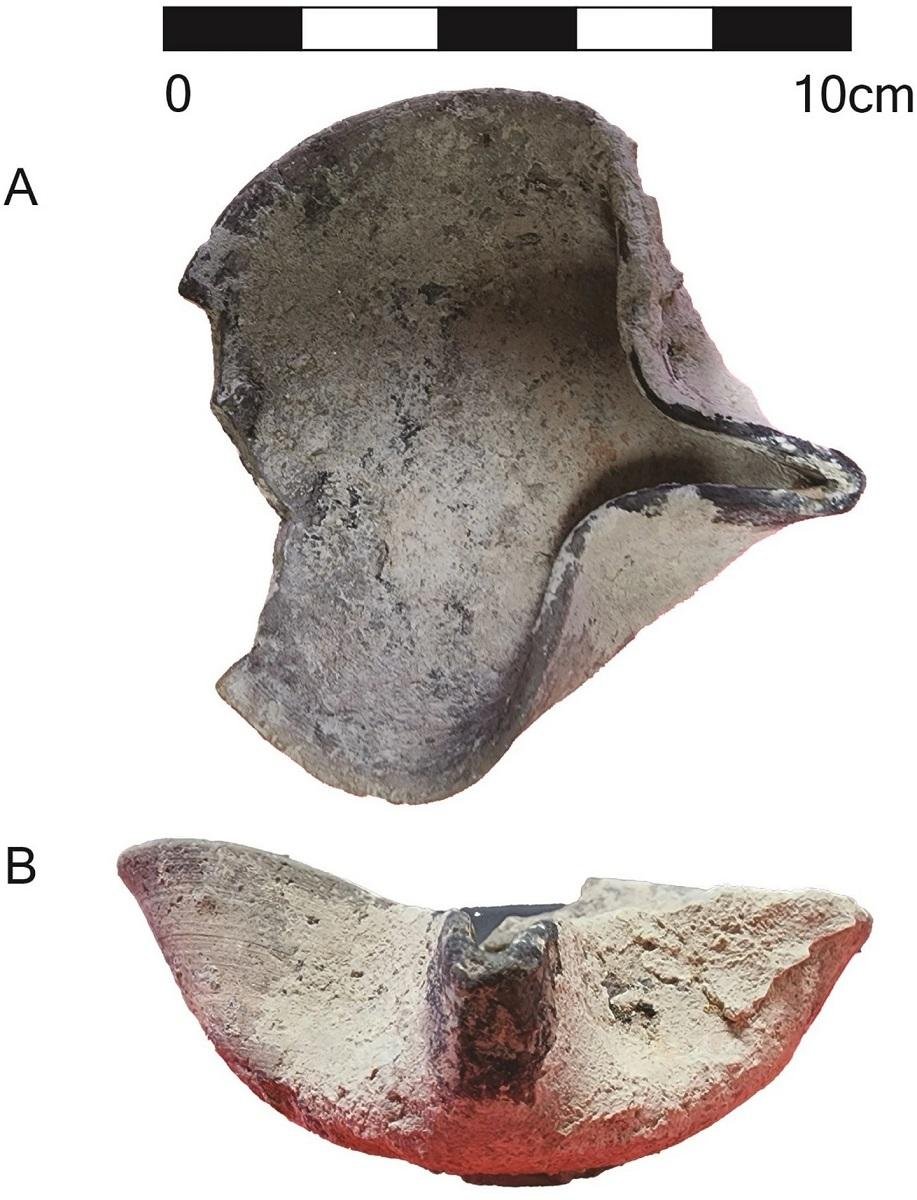

The gradient and flow marks within the tunnels indicate that they were designed to channel water under enough pressure to power paddle wheels driving downstream crushing mills. The mills extracted juice from harvested cane, which was then refined into sugar for export throughout the Mediterranean. A Mamluk oil lamp discovered at one of the mills provides archaeological evidence supporting this interpretation.

The working of a southern Levant sugar mill. A. Reconstruction of a sugar mill, modified after Stern (1999). B Excavated sugar mill at Masna’ as-sukkar, as-Safi. After Jones (2015). 1—chute; 2—water wheel; 3—lower (or fixed) millstone; 4—upper millstone (or runner). Credit: A. Frumkin et al., Water History (2025)

The working of a southern Levant sugar mill. A. Reconstruction of a sugar mill, modified after Stern (1999). B Excavated sugar mill at Masna’ as-sukkar, as-Safi. After Jones (2015). 1—chute; 2—water wheel; 3—lower (or fixed) millstone; 4—upper millstone (or runner). Credit: A. Frumkin et al., Water History (2025)

The system is a testament to Mamluk engineering ingenuity and their ability to adapt technology to local conditions. In a region where fresh water was scarce, they transformed brackish springs—of no use for drinking or irrigation—into a renewable source of energy. Carving tunnels directly into tufa rock also minimized evaporation and maintained water pressure, ensuring consistent mechanical power for the mills.

The discovery adds a new dimension to the history of the Mamluk Empire, which stretched from Egypt to Syria. Already famous for monumental public works such as aqueducts, baths, and mosques, the Mamluks are now shown to have had a sophisticated approach to industrial infrastructure as well. The Nahal ‘Amal tunnels show how they integrated geology, hydrology, and commerce to sustain one of their most valuable export industries.

A late Mamluk lamp (used until the sixteenth century CE) found at the eastern mill, downstream of the tunnels. A—top view; B—front view. Credit: A. Frumkin et al., Water History (2025)

A late Mamluk lamp (used until the sixteenth century CE) found at the eastern mill, downstream of the tunnels. A—top view; B—front view. Credit: A. Frumkin et al., Water History (2025)

Later, after sugar production declined, the same hydraulic system was reused in the Ottoman era to power flour mills, showing the continuity and adaptability of medieval water engineering.

The find challenges the perception of the medieval Levant as technologically stagnant. Instead, it portrays the Mamluks as pragmatic innovators who transformed environmental limitations into opportunities. By turning saline water into power, they created an industrial landscape that connected rural production with global trade.

More information: Frumkin, A., Yechezkel, A., Segal, D. et al. (2025). Water tunnels at Nahal ‘Amal (Israel): evidence of a water-based sugar industry in the Mamluk period?. Water History. doi:10.1007/s12685-025-00368-7