In Neolithic Europe, long before writing or metal tools, people relied on an incredible substance—birch bark tar. A new study, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, reveals that this black, sticky substance, found at lakeside settlements around the Alps, has retained an impressive molecular record of how early farmers lived, ate, and worked some 6,000 years ago.

Birch bark tar. Credit: Jorre; CC BY-SA 3.0

Birch bark tar. Credit: Jorre; CC BY-SA 3.0

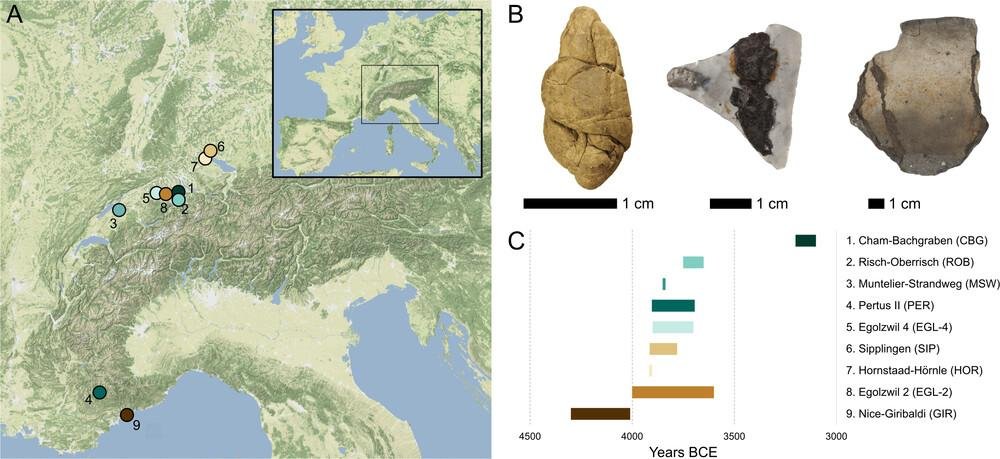

Archaeologists analyzed 30 birch tar pieces from nine Neolithic sites across the Alpine region. Some were found as loose lumps, while others were discovered as residue scraped from broken pottery or flint blades. With a combination of chemical analysis and ancient DNA sequencing, researchers confirmed that the samples were birch bark tar and uncovered human, plant, and microbial DNA trapped within.

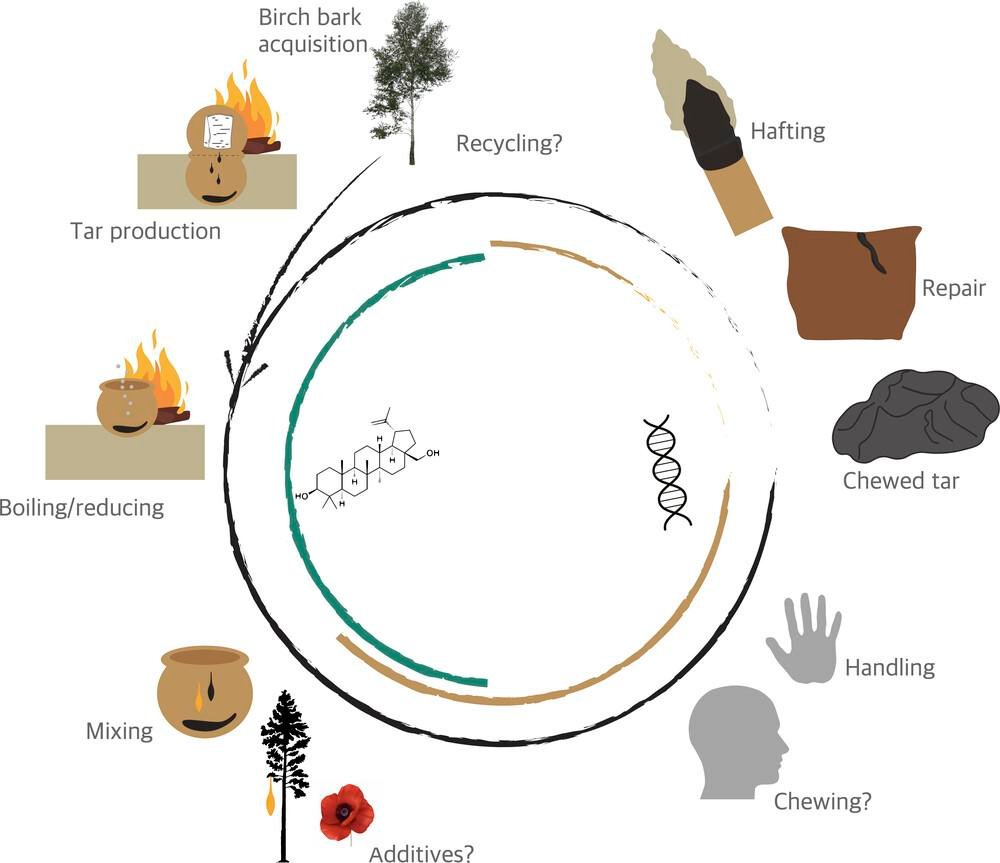

Birch tar, produced through the process of heating birch bark in conditions of low oxygen, was already recognized as one of humanity’s earliest synthetic substances, being primarily utilized as glue. However, the recent discoveries indicate that Neolithic individuals used it for much more. Several lumps had been chewed, containing human DNA from males and females, and traces of oral bacteria. These samples served as molecular “snapsH๏τs” of ancient humans quite effectively.

The presence of plant DNA—barley, wheat, peas, hazel, and beech—provides evidence that the chewers had recently eaten these foods, offering information on Neolithic diets. Conifer resin even appeared in a few tar lumps, likely added to change the material’s texture or adhesive strength. Scientists believe people chewed tar to soften it before use, or perhaps for hygiene or medicinal purposes.

Sites and samples studied in the research (PH๏τos by Theis Z. T. Jensen). Credit: A. White et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025).

Sites and samples studied in the research (PH๏τos by Theis Z. T. Jensen). Credit: A. White et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025).

Apart from chewing, the tar was also applied in everyday tasks. The presence of residue on pottery cracks shows that it was used to mend broken vessels. On flint blades, it was found where wood touched stone, confirming its role in hafting tools. In some pottery samples, the tar showed evidence of repeated heating, indicating reuse during cooking or food storage.

What is most amazing about these discoveries is that tar can act as a preservative for DNA in cases where human bones cannot. The waterlogged lake environments of these settlements would typically destroy skeletal material, but the waterproof, stable nature of the tar ensured that biomolecules were preserved over millennia. Each chewed lump or piece of resin became a tiny time capsule of personal and cultural information.

Making and using birch tar in Neolithic Europe. A possible chaîne opératoire from the initial production of birch tar to its final use, including potential recycling of tar, and the biochemical analyses used to investigate steps in this process. Credit: A. White et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025).

Making and using birch tar in Neolithic Europe. A possible chaîne opératoire from the initial production of birch tar to its final use, including potential recycling of tar, and the biochemical analyses used to investigate steps in this process. Credit: A. White et al., Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences (2025).

The study demonstrates how combining ancient DNA with organic residue analysis can reveal aspects of prehistoric life long thought lost—idenтιтy, diet, and technology—all through a tiny piece of resin. These tar samples show the practical ingenuity of Europe’s first farmers in transforming native materials into versatile tools and medicines.

More information: White, A. E., Koch, T. J., Jensen, T. Z. T., Niemann, J., Pedersen, M. W., Søtofte, M. B., … Schroeder, H. (2025). Ancient DNA and biomarkers from artefacts: insights into technology and cultural practices in Neolithic Europe. Proceedings. Biological Sciences, 292(2057). doi:10.1098/rspb.2025.0092