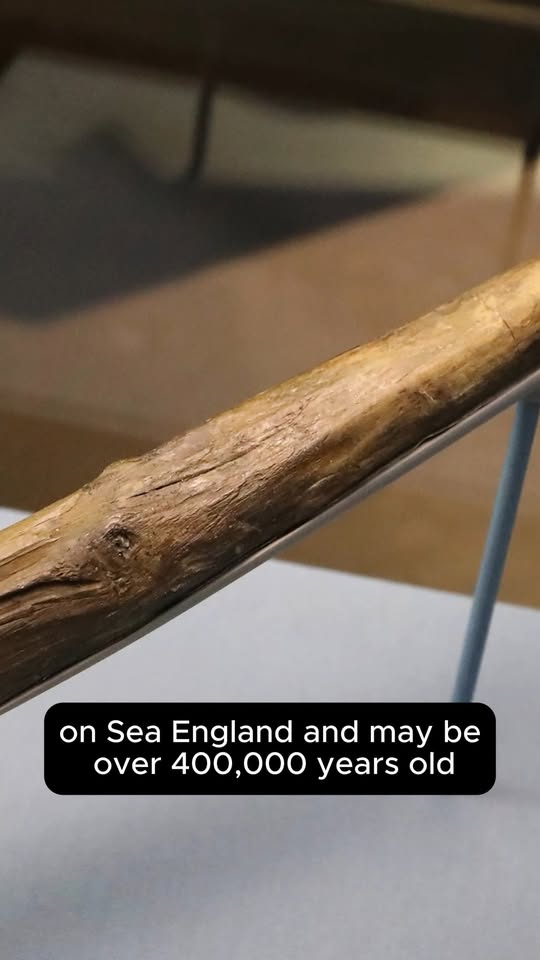

In a quiet display case in the Natural History Museum of London lies a relic so humble, so unᴀssuming, that many pᴀss it by without notice. A small piece of ancient yew wood, roughly shaped into a point, no longer than a forearm. Yet this fragile object — darkened by age and water, its grain etched with the touch of a forgotten craftsman — carries within it one of the oldest stories ever told by human hands.

It is the Clacton Spear, the earliest known wooden implement fashioned by early humans, dated to around 400,000 years ago. Found on the shores of Clacton-on-Sea, England, it stands as both an archaeological marvel and a profound symbol of the birth of human intelligence.

The Discovery

The spear was discovered in 1911 by a local man named Samuel Warren, during an excavation of gravel beds near Clacton-on-Sea in EsSєx. The area, long known for its ancient deposits, was part of what archaeologists call the Clactonian industry — a culture ᴀssociated with Homo heidelbergensis, the predecessor to both Neanderthals and modern humans.

At first glance, Warren could not have known what he held. To the untrained eye, it might have appeared as driftwood or a weathered branch. But scientists quickly realized that the object had been deliberately shaped — carefully carved and scraped to form a tapering point.

Radiocarbon dating was impossible for an object so old, but its age was established through stratigraphic analysis — the geological layers in which it was found. The spear emerged from sediments rich in fossils of elephants, rhinoceroses, and other Ice Age creatures, placing it firmly in the Lower Paleolithic period — nearly half a million years before written history.

A Spear of Yew and Vision

The Clacton Spear was made from yew wood, a choice that reveals both practical knowledge and skill. Yew is dense, strong, and flexible — ideal for tools and weapons. Its fibers resist splintering, and its natural oils make it resistant to decay. For early humans, who lived in a world of survival and scarcity, such understanding of materials marked a cognitive leap — a bridge between instinct and intellect.

The spear measures about 38.7 centimeters in length and 3.9 centimeters in diameter, with one end finely whittled into a point. Microscopic analysis reveals cut marks consistent with stone tools — suggesting deliberate shaping, not accidental wear. It was likely used as a thrusting spear, perhaps to hunt large prey or defend against predators.

Though simple in appearance, it represents something extraordinary: planning, intention, and foresight — the mental capacity to imagine a tool before it exists, and then bring it into being.

The Hands That Made It

To imagine the person who made the Clacton Spear is to glimpse a being both alien and familiar. Homo heidelbergensis stood tall, with a powerful frame and a large brain — roughly 90% the size of our own. They lived in a harsh, unpredictable landscape, amid glaciers and grᴀsslands, herds of mammoths and great cats.

Their lives were short and brutal, yet within them stirred the first sparks of creativity. The maker of the Clacton Spear would have sat beside a fire or stream, holding a length of green yew, turning it slowly in hand. Using sharp flakes of flint, they scraped, carved, and smoothed — testing the balance, the feel of the wood. They would have known, through experience pᴀssed down by generations, how to harden the tip in fire, how to keep it straight, how to wield it in the hunt.

This was not mere survival. It was craftsmanship — the transformation of nature through thought.

A World Before History

Four hundred thousand years ago, England was not the island we know today. It was part of a vast land bridge connecting Britain to continental Europe — a landscape of forests, rivers, and open plains roamed by early humans and Ice Age fauna.

The climate shifted dramatically between warm interglacial periods and freezing epochs. These early people followed the migrations of animals — elephants, red deer, hippos — building temporary camps near rivers, crafting tools from flint and bone, and scavenging what the wilderness provided.

Their technology was primitive but effective. The Clactonian culture produced crude stone flakes and cores, lacking the refined hand-axes of later Acheulean technology. Yet the spear shows that even at this early stage, they possessed a deep practical intelligence — an understanding of leverage, balance, and purpose.

The Symbolism of a Spear

In many ways, the Clacton Spear marks the birth of the human imagination. It represents not only a tool, but an idea — the recognition that the environment could be reshaped, that survival could be enhanced through innovation.

It is a symbol of transition: from prey to hunter, from instinct to intention, from nature’s child to its challenger.

The spear was more than wood; it was an extension of the self — a projection of power, distance, and control. For the first time, a being could strike beyond the reach of its own body. That realization may have changed everything.

Weapons such as this were the ancestors of all later tools — from ploughs to pens, from bows to telescopes. In carving wood into a point, early humans began carving their destiny.

The Fire Within

Perhaps most remarkable is the evidence that the makers of this spear may have used fire — not merely as warmth or light, but as a tool. Experiments by modern archaeologists have shown that gently charring the tip of a wooden spear before sharpening it hardens the fibers, giving it greater durability.

If this was indeed done by Homo heidelbergensis, then they were already manipulating the elements to serve their needs — a feat once thought exclusive to much later humans.

To hold fire and shape wood is to hold both destruction and creation in one’s hands — the dual nature of humanity itself.

The Fragility of Memory

For centuries, wooden tools like this were believed to be impossible to preserve — perishable artifacts that would vanish long before stone survived. The Clacton Spear survived only because it was buried in waterlogged sediments, sealed away from oxygen. It is a miracle of preservation, a time capsule from before language, before myth, before civilization.

When scientists examine it today, they see not just the marks of ancient tools but the fingerprints of thought — grooves and scratches that speak of decision and repeтιтion, trial and error. The spear is both artifact and autobiography: a record of the human mind awakening.

A Relic of the Dawn

To stand before the Clacton Spear is to confront time itself. It forces us to ask — what does it mean to be human? Where did understanding begin?

Long before art, before music, before writing, there was the will to create something that did not exist before — a will to survive, to shape, to dream. In that sense, this small piece of wood is the oldest evidence of our shared story.

It is the first whisper of invention — the dawn of technology, of craft, of meaning. From this wooden point grew the arrow, the bow, the plough, the pen, the ship, and finally, the world we know.

The Continuum of Creation

Every tool, from the simplest to the most complex, carries the legacy of that first act of creation. The Clacton Spear reminds us that ingenuity is not new — it is ancient, embedded in our bones. The same spark that drove its maker to shape wood into a weapon now drives us to shape silicon into circuits, to explore the stars, to preserve our past.

Human history, in its essence, is the story of transformation — of turning the raw into the refined, the ordinary into the extraordinary.

And yet, the Clacton Spear also teaches humility. For all our progress, we remain bound to the same instincts: the need to survive, to adapt, to understand. We are not separate from our ancestors; we are their continuation.

The Echo of Hands

Imagine the moment — a hand, roughened by labor, grasping a piece of yew wood, pressing against it, feeling its weight. That hand, now dust, once held purpose. That purpose shaped a tool. That tool shaped a future.

Across 400,000 years, that gesture reaches us still.

The Clacton Spear, preserved in silence and shadow, is not merely a museum piece. It is a message — that intelligence did not arrive suddenly with us, but grew slowly, like a tree from the soil of instinct. It is a reminder that creativity is as old as our species — and perhaps older still.

Epilogue

In the polished glᴀss of the museum case, the spear lies motionless, yet its presence vibrates with unseen life. It is the ghost of a forgotten forest, the echo of ancient footsteps along the edge of a vanished sea.

Before pyramids, before writing, before words, someone knelt in the dust and made this.

A tool. A weapon. A thought.

And from that moment — that single spark of imagination — humanity began.