A new study published in Current Anthropology may have solved one of the largest mysteries of ancient Mesoamerica—the language spoken in Teotihuacan, the vast metropolis that dominated central Mexico nearly two thousand years ago.

The Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan in Mexico. Credit: Christophe Helmke, University of Copenhagen

The Mesoamerican city of Teotihuacan in Mexico. Credit: Christophe Helmke, University of Copenhagen

Teotihuacan, founded around 100 BCE and abandoned by 600 CE, was one of the largest cities of the ancient world, home to more than 100,000 people at its zenith. It was a cultural and political hub whose influence spread across Mesoamerica, with monumental pyramids, wide avenues, and intricate painted murals. Yet despite decades of excavation, a question has remained for years: what language its inhabitants spoke → what language did its inhabitants speak?

Researchers Christophe Helmke and Magnus Pharao Hansen of the University of Copenhagen now propose that Teotihuacan’s murals and artifacts preserve an early Uto-Aztecan language, the ancestor of later languages such as Cora, Huichol, and Nahuatl—the language of the Aztecs. Their study provides evidence for a direct link between the people of Teotihuacan and later Nahuatl-speaking populations, implying the Aztecs may be descendants of this earlier urban civilization.

The researchers’ conclusions derive from years of detailed examination of signs found on Teotihuacan’s murals and pottery. Scholars have wondered for a long time whether the images were merely decorative or represented a writing system. Helmke and Hansen think they do both: some signs are logograms, pictorial representations of entire words—a coyote for the word “coyote,” for instance—while others form phonetic compounds, or rebuses, that represent sounds, not meanings. This dual use of signs marks the system as a true writing system.

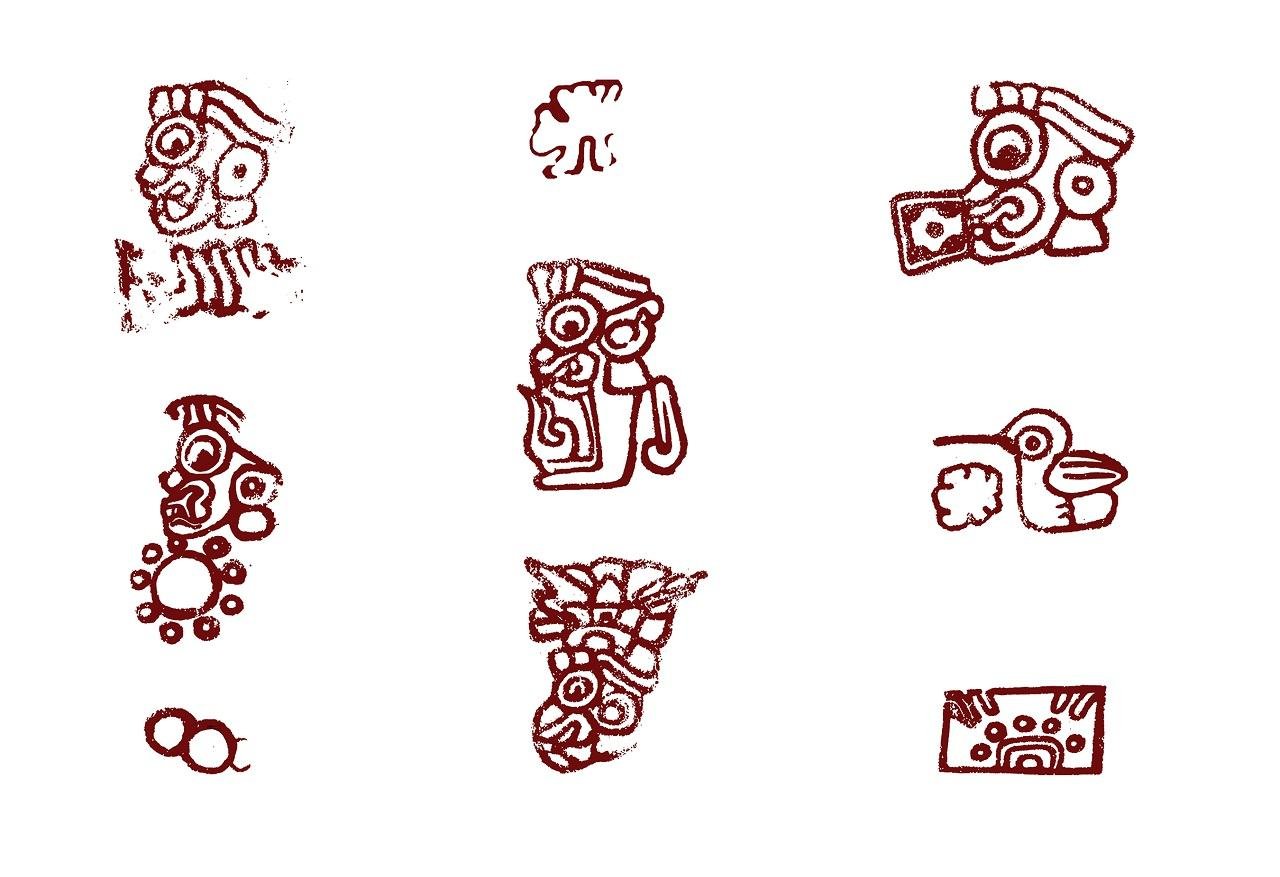

Examples of glyphic signs in the Teotihuacan writing system. Credit: Christophe Helmke, University of Copenhagen

Examples of glyphic signs in the Teotihuacan writing system. Credit: Christophe Helmke, University of Copenhagen

Deciphering it is no simple process, however. Because the Uto-Aztecan family changed so much over time, Pharao Hansen first had to reconstruct what the language would have sounded like more than 1,500 years ago. Only then could they determine whether the mural signs fit the linguistic pattern of that early stage.

So far, the texts available to study are limited, found mainly on wall paintings and decorated ceramics. However, the researchers have identified recurring signs and grammatical clues that support their interpretation. They hope that new discoveries will confirm their theory and enable a more comprehensive translation of the inscriptions in the city.

Teōtīhuacān, known as the “birthplace of the gods” by the Aztecs, flourished between 100 BCE and 600 CE, during which it grew into a bustling metropolis characterized by monumental structures such as the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. Credit: Jorge Acre

Teōtīhuacān, known as the “birthplace of the gods” by the Aztecs, flourished between 100 BCE and 600 CE, during which it grew into a bustling metropolis characterized by monumental structures such as the Pyramid of the Sun, the Pyramid of the Moon, and the Temple of the Feathered Serpent. Credit: Jorge Acre

If correct, the find would dramatically rewrite the history of central Mexico. Archaeologists have long believed that speakers of Nahuatl moved into the region only after Teotihuacan’s collapse. The new evidence instead implies a continuous linguistic and cultural tradition from Teotihuacan to the later Aztec Empire nearly a millennium later.

Helmke and Hansen emphasize that their work is only the beginning. They are now inviting colleagues worldwide to join collaborative workshops aimed at testing and expanding their decoding method. Beyond revealing a long-lost language, their study offers a new way to approach the earliest writing systems of Mesoamerica.

“If we’re right,” Helmke noted, “it is not only remarkable that we have deciphered a writing system. It could have implications for our entire understanding of Mesoamerican cultures and, of course, point to a solution to the mystery surrounding the inhabitants of Teotihuacan.”

More information: University of CopenhagenReference: Pharao Hansen, M., & Helmke, C. (2025). The language of Teotihuacan writing. Current Anthropology, 66(5), 705–739. doi:10.1086/737863