The Eternal Watchers of Abu Simbel

The desert is vast, silent, and unforgiving. The sun blazes mercilessly upon golden sands that stretch to the horizon. Yet, rising from the rock face of a Nubian cliff near the Nile, four colossal figures stare out with unyielding calm, as if they have been waiting for eternity itself. This is Abu Simbel—the great temple of Ramses II—one of the most breathtaking achievements of ancient Egypt, and a monument not only to power but also to human resilience and devotion across time.

Arrival at the Edge of the Desert

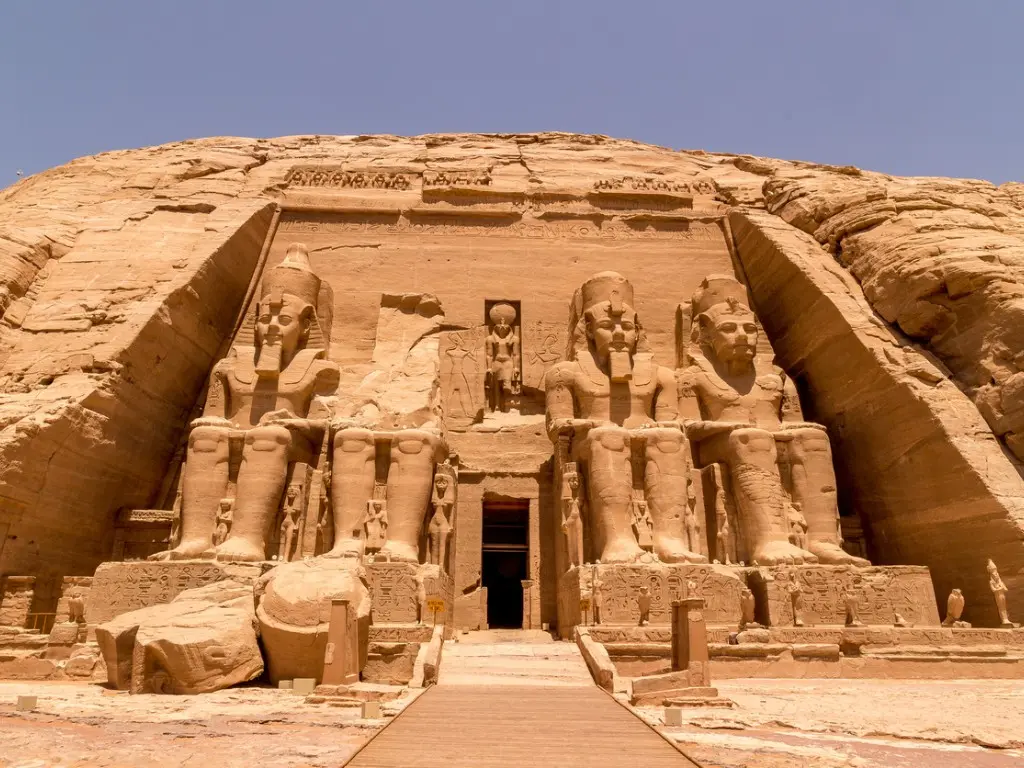

Travelers who approach Abu Simbel feel it before they see it. The air shifts, the desert seems to hush, and the sandstone cliffs loom higher. Then, suddenly, the façade emerges, carved directly into the mountain: four seated statues of Ramses II, each towering more than twenty meters high, staring outward with a gaze both serene and intimidating. Their sheer scale dwarfs any human presence, a reminder of the Pharaoh’s desire to project his might not only to his subjects but to the gods, to his enemies, and to time itself.

At their feet, smaller statues of queens, children, and symbolic figures line the base, as if all humanity is arranged beneath the grandeur of the Pharaoh. To stand before them is to feel both awe and humility, as though one has stepped into a realm where mortal boundaries dissolve.

Ramses II: The Builder King

Ramses II, known as Ramses the Great, was one of the longest-reigning pharaohs of Egypt, ruling for 67 years during the 13th century BCE. His reign marked the height of Egypt’s power and wealth. His ambitions were grand, his ego monumental. Where other kings left tombs or temples, Ramses left an empire carved in stone.

Abu Simbel was his masterstroke in Nubia, the southern frontier of his realm. More than a temple, it was a statement. Facing toward the Nile and the lands beyond, it was both a warning and a promise: a warning to those who might challenge Egyptian power, and a promise to the gods that Ramses would ensure the eternal glory of their worship.

The temple was dedicated to the gods Amun, Ra-Horakhty, and Ptah, but above all, it was dedicated to Ramses himself, a god among men. In its design, his figure dominates, not only on the façade but also within, where his likeness is repeated again and again, etched into walls and columns as if to say: I am eternal.

The Miracle of the Sun

The Egyptians believed in harmony between the cosmos and their monuments. Abu Simbel is a perfect example of this belief, aligned so precisely that twice a year, on February 22 and October 22, the rising sun pierces the temple’s inner sanctuary. On these days, the first light touches the statues of Ramses II, Ra-Horakhty, and Amun, illuminating them in golden brilliance—while the statue of Ptah, god of the underworld, remains cloaked in shadow.

These solar events are not mere coincidences; they are proof of the Egyptians’ advanced understanding of astronomy and engineering. Imagine the awe of the ancient priests and followers as they gathered to witness the sun breathe life into the stone, affirming Ramses’s divinity and the favor of the gods. Even today, thousands of people travel from across the globe to see this miracle of light, connecting themselves to a ritual that has continued for over three millennia.

Archaeology and Rediscovery

For centuries, Abu Simbel lay buried beneath the desert sands, nearly forgotten. It was not until 1813 that Swiss explorer Johann Ludwig Burckhardt stumbled upon the temple’s upper façade. Soon after, Italian adventurer Giovanni Belzoni excavated the entrance, unveiling the colossal statues to the modern world. The sight stunned Europe, igniting Egyptomania and inspiring scholars, artists, and poets.

But the greatest challenge for Abu Simbel came in the 20th century. In the 1960s, Egypt embarked on the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which promised prosperity but threatened to submerge Abu Simbel beneath the waters of Lake Nᴀsser. The thought of losing such a treasure shook the world.

In an unprecedented act of global cooperation, UNESCO launched an international campaign to save the temples. Between 1964 and 1968, engineers, archaeologists, and workers carefully cut the temple into giant blocks—some weighing over 30 tons—and reᴀssembled them on higher ground, piece by piece, like an ancient puzzle reborn. It was one of the most extraordinary feats of modern engineering, a rescue mission that preserved not only stone but memory, legacy, and idenтιтy.

Today, when visitors stand before Abu Simbel, they are not only gazing at an ancient wonder but also at a monument to human determination—the collaboration of countless people across continents who refused to let the sands or the waters erase this masterpiece.

The Human Experience

To stand before Abu Simbel is to feel your own heart slow. The colossal statues stare ahead, their features calm, unbothered by centuries of storms, invasions, or floods. They radiate permanence, as though nothing—not even the erosion of time—can truly touch them. And yet, cracks, weathering, and missing fragments remind us that even the eternal can be fragile.

Inside the temple, the air is cooler, the light dimmer, and the silence almost sacred. Reliefs on the walls depict scenes of Ramses’s military victories, most famously the Battle of Kadesh, where the Pharaoh, larger than life, drives his chariot into the fray. These images are not mere history—they are propaganda, carefully crafted to project invincibility. For the Egyptians, they were truths carved into eternity.

As you walk deeper into the sanctuary, you sense that you are moving not only through space but through layers of belief, ambition, and faith. Here, ancient priests once whispered prayers, incense once drifted upward, and the voices of worshippers once echoed against the stone. The ghosts of those moments still linger, carried by the walls themselves.

Emotion and Legacy

Abu Simbel is not just about Ramses II. It is about us. It is about humanity’s longing to outlast mortality, to carve permanence into impermanence, to reach for eternity with mortal hands. Ramses built Abu Simbel to be remembered, and in this he succeeded. More than 3,000 years later, people still speak his name, still marvel at his monuments, still feel the weight of his presence.

But there is another layer of emotion—because Abu Simbel is also a monument to memory saved. The story of its rescue by UNESCO reminds us that heritage belongs not to one nation but to all humanity. It shows that when we choose to value the past, we preserve not only stone but the essence of what makes us human: our stories, our creativity, our ability to imagine greatness.

Standing before the temple, you feel awe, yes, but also graтιтude—for the hands that built it, the hands that rediscovered it, and the hands that saved it. It is a chain of connection stretching across centuries, linking ancient masons with modern engineers, ancient priests with modern tourists, and Ramses II himself with you, standing in the desert heat, gazing up at the colossus.

The Paradox of Time

There is an irony to Abu Simbel. Ramses II sought immortality through stone, and in many ways he achieved it. Yet the monument’s survival was not due solely to his will, but to the efforts of people thousands of years later who refused to let it vanish. His immortality, then, is not just a triumph of kingship but of humanity’s collective memory.

And as you stand there, you wonder: What will we leave behind? What monuments, stories, or ideas will carry our names into the future? Abu Simbel does not only speak of the past—it challenges us to think of our own eternity.

Conclusion: The Eternal Watchers

As the sun sets over the Nubian desert, the statues of Ramses II glow with a warm, golden light. Their gaze remains fixed, unwavering, eternal. They have seen empires rise and fall, seen the desert shift and the river change its course. They have survived burial, rediscovery, and even relocation. And still, they endure.

The watchers of Abu Simbel are more than stone. They are the embodiment of a dream—a dream of permanence in a world of impermanence, a dream that spans millennia, a dream that continues to live each time a visitor stands in awe and whispers, Ramses.

For in that whisper, the Pharaoh lives again. And in that moment, we too touch eternity.