Archaeologists from Lund University have shed new light on the artillery of Gribshunden, the late medieval Danish-Norwegian King Hans’ flagship that sank in 1495 off Ronneby (Sweden). The ship, labeled the world’s best-preserved vessel from the cusp of the Age of Exploration, provides unique insight into the technological developments that facilitated European maritime dominance.

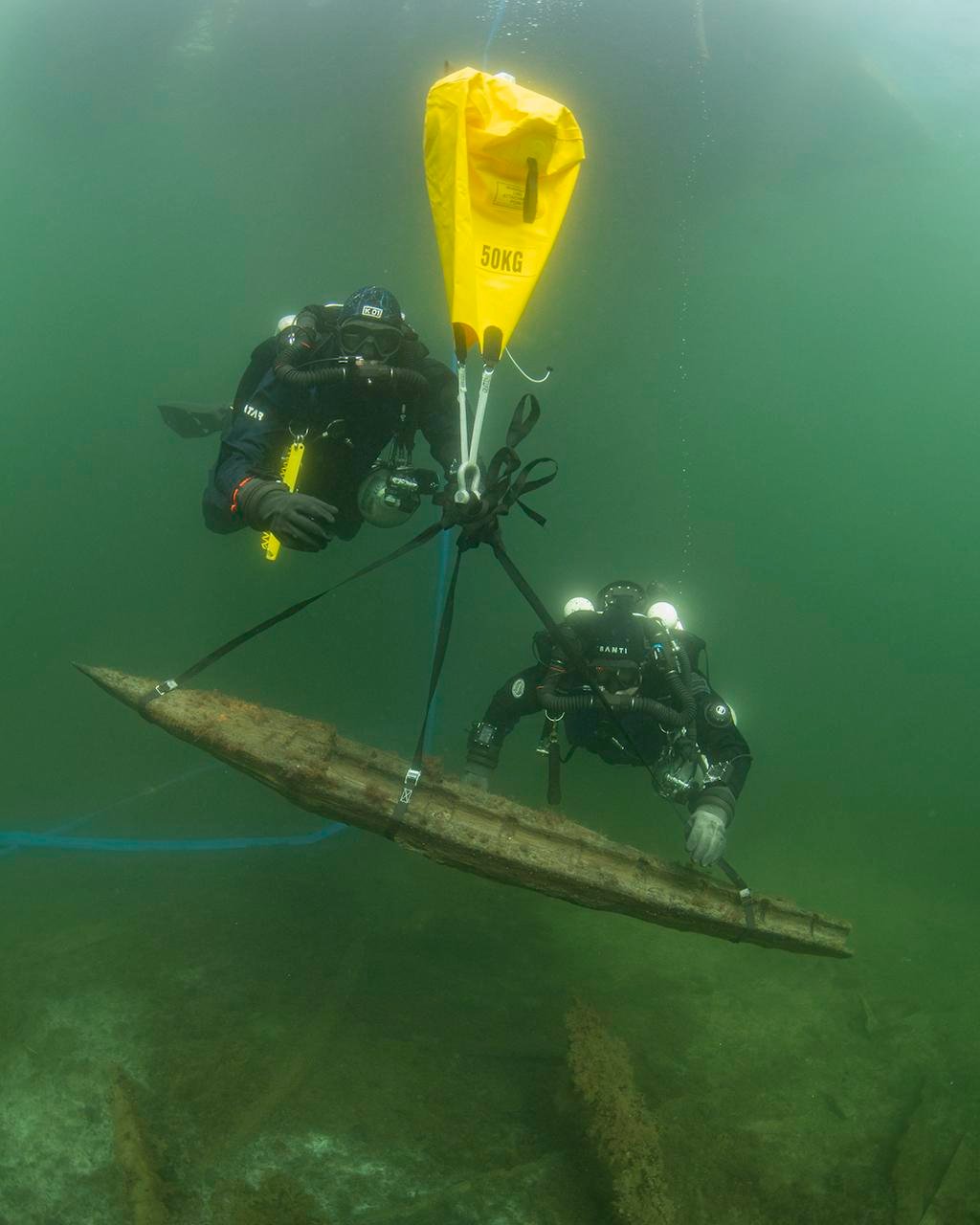

Recovery of the artillery gun bed in 2021 by Lund University and Blekinge Museum. Credit: Klas Malmberg

Recovery of the artillery gun bed in 2021 by Lund University and Blekinge Museum. Credit: Klas Malmberg

The research, published in the International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, examines the ship’s arsenal of more than 50 small-caliber guns designed to fire lead balls with iron cores. Unlike the heavier cannons that later became standard for smashing hulls, these were primarily anti-personnel weapons. Crews used them to unleash volleys at close range, disabling enemy sailors before boarding their vessels. Several of the 22 surviving projectiles are flattened—likely the result of the explosion and fire that sank the ship while it lay at anchor.

“Diving on this late medieval royal shipwreck is, of course, exciting,” said Brendan Foley, a marine archaeologist at Lund University and co-author of the paper. “However, the greatest satisfaction comes when we can piece the puzzle together, combining Martin’s expertise in castles with Kay’s deep knowledge of artillery.” Foley worked closely with archaeologist Martin Hansson and medieval artillery expert Kay Douglas Smith.

Built in 1483–1484 near Rotterdam, Gribshunden was the high point of ship design at the time. Its carvel construction—a method pioneered in Iberia—allowed for larger and more powerful vessels to carry heavy weaponry. King Hans acquired the vessel in 1486, and it cost as much as 8% of Denmark’s national budget. He used the ship more as a sea fortress than as an expedition ship, and he sailed it himself on royal travels around his realm.

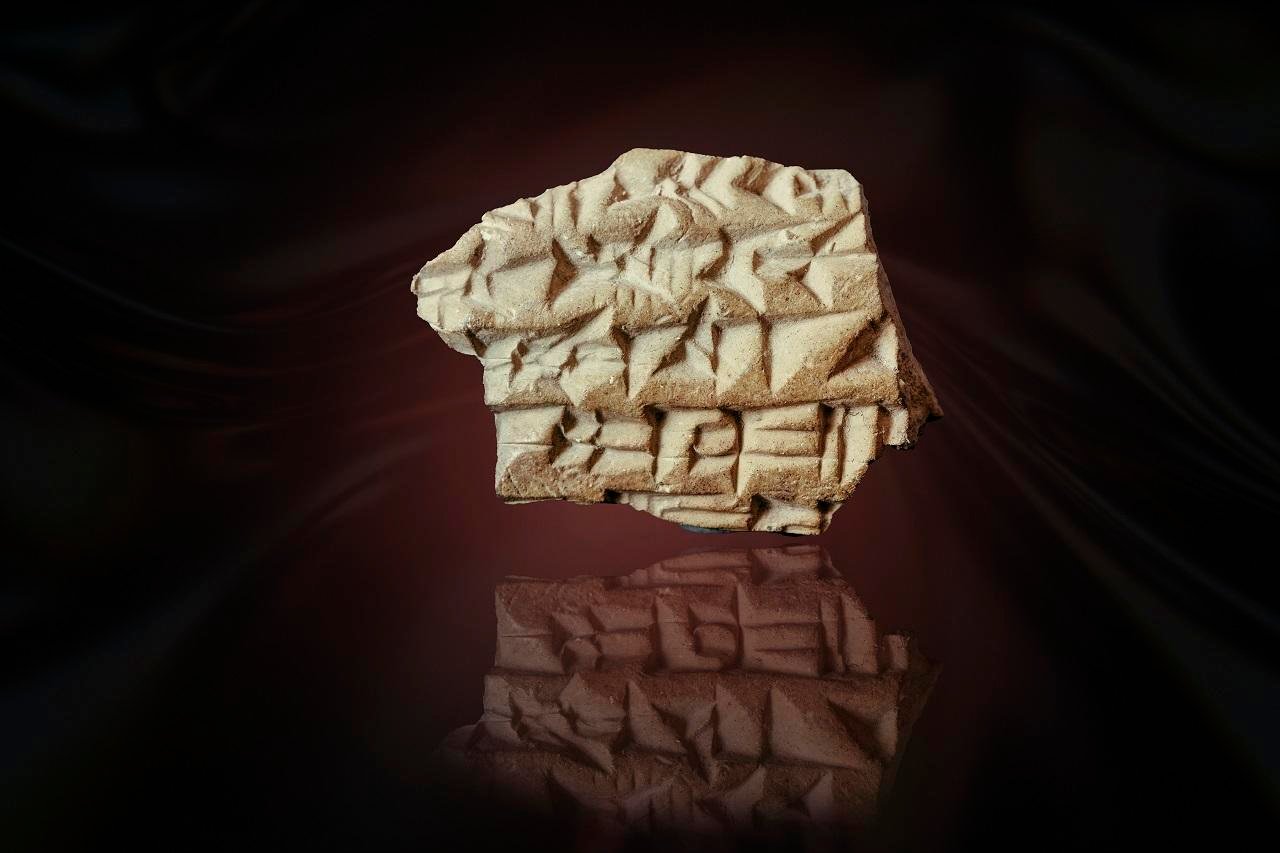

Gribshunden wooden artillery beds after conservation, curated at Blekinge Museum. Credit: Brendan Foley

Gribshunden wooden artillery beds after conservation, curated at Blekinge Museum. Credit: Brendan Foley

The ship served Hans for a decade before its disastrous end. History recounts how, when Hans was ashore in Ronneby at a summit to attempt to bring the Nordic kingdoms together under the Kalmar Union, his prized flagship was destroyed by fire and explosion.

The study not only pinpoints Gribshunden’s remarkable preservation but also situates it in wider European maritime history. Eleven of the original guns were reconstructed digitally by archaeologists led by Professor Nicolo Dell’Unto and his team at Lund University. The work reveals how, during the late 15th century, small-bore serpentines became the default naval armament—a period of transition before larger iron cannons transformed naval combat after 1500.

The research leader for the entire excavation, Brendan Foley, at the Gribshunden shipwreck. Credit: Brett Seymour

The research leader for the entire excavation, Brendan Foley, at the Gribshunden shipwreck. Credit: Brett Seymour

Even with Denmark and Norway’s rich seafaring tradition—dating to Viking settlements in Iceland, Greenland, and even North America—Hans did not compete with Spain and Portugal in overseas expansion. A number of reasons were behind this, such as his preoccupation with consolidating power in the Baltic and a papal bull from Pope Alexander VI in 1493. The decree granted exclusive rights to the Americas to Spain and the Indian Ocean to Portugal, threatening excommunication for any ruler who defied it.

As Foley explained, the Gribshunden is the best-preserved ship from the time of exploration and gives historians a model for the types of vessels used by Christopher Columbus and Vasco da Gama.

Shipwreck artifacts, including artillery pieces, are now housed at the Blekinge Museum and other insтιтutions. Plans are underway to establish a dedicated museum for Gribshunden at Ronneby to keep the finds in a permanent exhibition.

More information: Lund UniversityPublication: Foley, B., Smith, K. D., & Hansson, M. (2025). Late medieval shipboard artillery on a northern European Carvel: gribshunden (1495). International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 1–26. doi:10.1080/10572414.2025.2532166