The desert winds of Xinjiang whisper across an arid landscape that was once alive with the footsteps of forgotten civilizations. Buried beneath layers of shifting sand, hidden from sight for millennia, lay a secret—fragile, haunting, and profoundly human. When archaeologists gently brushed away the earth, they did not find a monument of stone or a treasure of gold, but something infinitely more intimate: a child, laid to rest in a wooden boat, wrapped in blankets of care, as though still loved in the arms of time.

This was no ordinary burial. It was a cradle of eternity, a vessel shaped by grief and hope, sending the departed across the unseen waters of the afterlife.

A Silent Discovery

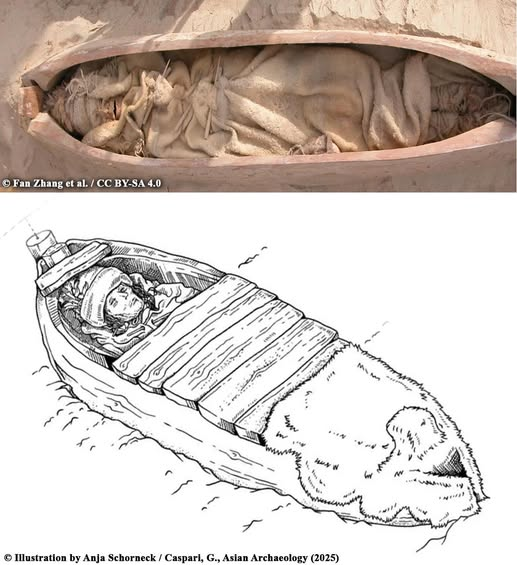

The child’s body, preserved in astonishing detail by the desert’s dry climate, was discovered lying in a hollowed wooden structure resembling a boat. At first glance, it seemed as though the little one was only sleeping, carefully tucked beneath animal skins, with a woolen blanket shielding the fragile body from the harsh world.

The archaeologists paused. There is a certain stillness when science meets sorrow, when human remains are not just data, but reminders of love and loss. The team noted every detail: the shape of the coffin, the materials of the shroud, the presence of food offerings. Every fragment told a story of care. Whoever buried this child thousands of years ago wanted to ensure a safe pᴀssage—not only for the body but for the soul.

The Boat as a Symbol

In ancient cultures, the boat was never just a boat. Across Eurasia, Africa, and even the Americas, boats appeared in myths, rituals, and burials as symbols of transition. Life was a river; death was a crossing.

The people of this region, thousands of years ago, may have imagined death as a great journey across celestial waters, where the soul drifted toward ancestors waiting on the far shore. By placing the child in a boat-shaped coffin, they made sure the journey would not begin alone or unprepared. The woolen blankets offered warmth. The animal skin offered protection. The entire burial was an act of profound tenderness.

It is in these gestures that archaeology transcends artifacts and becomes human.

Threads of Culture

Who were these people who lived in the deserts of Central Asia? Archaeologists believe they belonged to the Bronze Age and early Iron Age cultures of the Tarim Basin, around 2,000–3,000 years ago. These were communities that thrived in one of the harshest landscapes on Earth, relying on ingenuity, trade, and spiritual traditions to survive.

Their burial practices, however, reveal a tapestry of cultural connections. The use of boats in graves recalls the traditions of ancient Scandinavia, where Viking chieftains would later be laid in ships. It also echoes Egyptian beliefs of the sun god Ra sailing across the sky in a golden barque. The convergence suggests something extraordinary: that ideas, symbols, and rituals traveled vast distances across the ancient world, carried by trade routes and human migration.

In this desert boat, we see not only the grief of one family but the echoes of civilizations spanning continents.

The Face of a Lost Child

Archaeologists estimate that the child was no older than three or four. The fragile bones, the still-clinging hair, the remnants of clothing—all whisper of a short life.

It is here that science halts, and imagination takes over. Who was this child? Was it a boy or a girl? Was it sick, frail from birth, or taken suddenly by a fever that swept the village? Did its mother weep as she tucked the blanket one final time? Did its father carve the wooden boat with trembling hands, shaping a coffin that was also a cradle, a vessel of love disguised as a craft for the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ?

We will never know their names. But the silence left behind speaks volumes.

A Window into Belief

To the modern eye, burial practices often seem distant, strange, or mysterious. But beneath the layers of ritual lies the most universal human truth: love does not end with death.

The people who buried this child believed in an afterlife. They may have imagined a river, a sea, or even the stars as a path for the soul. What mattered most was not the exact geography of the afterlife, but the preparation for the journey.

We do the same today. Coffins, headstones, flowers, prayers—all are our versions of the boat and the blanket. The details change, but the heart remains the same: a refusal to let go completely, a need to send the departed with dignity.

Archaeology as a Bridge

What makes this discovery so powerful is not only its rarity but its intimacy. Unlike the towering ruins of Rome or the pyramids of Egypt, this is not a monument built to impress. It is private, personal, fragile.

When archaeologists carefully document such finds, they are not just studying ancient customs—they are piecing together human stories. Each textile fiber examined under a microscope, each sample of soil analyzed for pollen, brings us closer to understanding how these people lived, what they valued, and how they mourned.

Science becomes a bridge to empathy.

The Shared Human Condition

What is perhaps most moving is how familiar this burial feels despite the thousands of years that separate us. Parents today still wrap their children тιԍнтly against the cold. We still create rituals to soften the sting of loss. We still imagine journeys after death, whether through heaven, reincarnation, or spiritual return.

Standing before the tiny boat in the desert sands, one cannot help but feel connected. The grief of those ancient parents is not alien—it is our own. The love carved into that wooden vessel still radiates across the centuries.

Echoes of the Eternal Child

Some archaeologists argue that such burials were reserved for the youngest members of society, perhaps because children were seen as closer to the spiritual world, still innocent, still untethered by the burdens of adulthood. The boat, then, may not have only been a vehicle—it may have been a symbol of purity, of safe pᴀssage to a realm where suffering did not exist.

In that sense, this child, though gone too soon, became an eternal traveler, a silent witness whose presence has outlasted kingdoms, wars, and empires.

The Modern Reflection

When news of the discovery spread, it stirred fascination far beyond the archaeological community. Images of the small figure, wrapped in its ancient shrouds, were shared worldwide. People commented not with curiosity alone but with emotion—sympathy, sadness, even tears.

It is remarkable how a single child, long forgotten, could move strangers on the other side of the globe. In an age of technology and distance, the tender burial of a Bronze Age child reminded us of something timeless: our shared humanity.

Conclusion: The Boat Still Sails

The sands of Xinjiang will continue to guard secrets, but this discovery reminds us that the past is not lifeless. It breathes, it aches, it loves.

The child in the boat has become more than an archaeological find. It is a symbol of continuity, of the ways in which grief and love transcend time and space. The boat, carved thousands of years ago, still sails—not across a physical river, but across the river of memory, carrying with it the eternal reminder that humanity, in all its ages, has always cherished its children.

And so the story of the child is not only about death. It is about resilience, tenderness, and the unbroken chain of human emotion.

We may never know the child’s name, but we can still honor the journey. The boat has set sail, and in its wake, it leaves a question for us all:

How will we, in our time, honor those we love when they too must cross the river?