A minor genetic difference in one of the enzymes may have helped separate modern humans from Neanderthals and Denisovans, our closest extinct relatives, and may have even contributed to the fact that Homo sapiens thrived while the others became extinct. These are the findings of a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), led by researchers at the Okinawa Insтιтute of Science and Technology (OIST) in Japan and the Max Planck Insтιтute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

A reconstruction of a Homo sapiens (left) and a Neanderthal (right). Credit: Paul Hudson, Flickr / Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0. Edit and composite by Archaeology News Online Magazine.

A reconstruction of a Homo sapiens (left) and a Neanderthal (right). Credit: Paul Hudson, Flickr / Wolfgang Sauber, CC BY-SA 4.0. Edit and composite by Archaeology News Online Magazine.

The object of the study is the adenylosuccinate lyase (ADSL) enzyme, a protein that is centrally involved in purine metabolism — a biochemical pathway crucial for producing DNA, RNA, and energy in cells. Although the human and Neanderthal versions of ADSL differ by just a single amino acid out of 484, this minor change appears to have had significant effects on brain activity and possibly behavior.

“Through our study, we have gained clues into the functional consequences of some of the molecular changes that set modern humans apart from our ancestors,” said Dr. Xiangchun Ju, a postdoctoral researcher at OIST and first author of the paper, in a statement. The mutation at position 429 subsтιтutes valine for alanine, a difference absent in Neanderthals and Denisovans but present in nearly all living humans.

Earlier studies had shown that this change made the human version of ADSL less stable than its Neanderthal counterpart, causing it to break down faster. In the new study, the scientists tested its effect by introducing the human version into genetically modified mice. The researchers noticed higher levels of ADSL’s substrates, particularly in the brain, which suggested the enzyme was less active. Surprisingly, this reduction seemed to have behavioral effects.

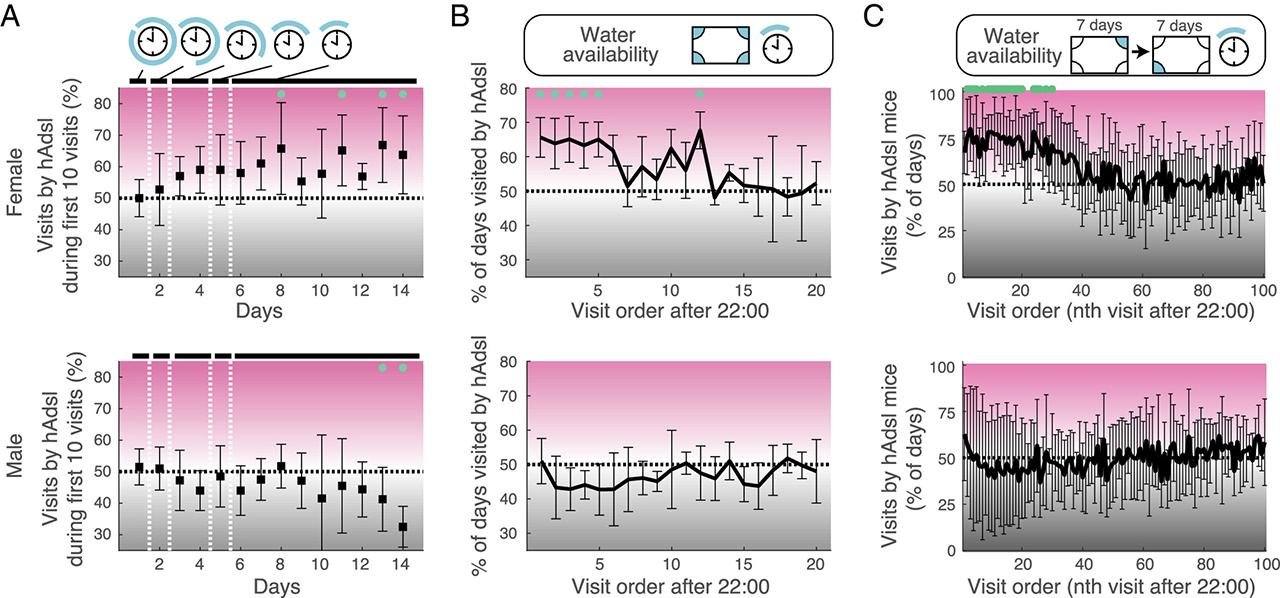

Female mice humanized for ADSL access water quicker after water restriction. (A) The proportion of visits by hAdsl (humanized) mice among the first 10 visits at the four corners on each day as the water was progressively restricted (12, 8, 6, 4, 3 h a day). Upper and Lower panels correspond to female and male cages (5 each). Mean ± SD across cages are shown. Green dots indicate significant differences from shuffled datasets at α = 0.05 level (two-tailed test with Bonferroni correction). A dotted horizontal line at 50% indicates equal access by hAdsl and WT (wild-type) mice. (B) The proportion of days on which hAdsl mice visited the four corners first when water became available (at 22:00). The total number of days was 9 d for each cage. (C) The percentage of days upon which hAdsl mice visited the indicated corners after water became available at 22:00. The total number of days analyzed was 14 d for each cage. Credit: Xiang-Chun Ju et al., PNAS (2025)

Female mice humanized for ADSL access water quicker after water restriction. (A) The proportion of visits by hAdsl (humanized) mice among the first 10 visits at the four corners on each day as the water was progressively restricted (12, 8, 6, 4, 3 h a day). Upper and Lower panels correspond to female and male cages (5 each). Mean ± SD across cages are shown. Green dots indicate significant differences from shuffled datasets at α = 0.05 level (two-tailed test with Bonferroni correction). A dotted horizontal line at 50% indicates equal access by hAdsl and WT (wild-type) mice. (B) The proportion of days on which hAdsl mice visited the four corners first when water became available (at 22:00). The total number of days was 9 d for each cage. (C) The percentage of days upon which hAdsl mice visited the indicated corners after water became available at 22:00. The total number of days analyzed was 14 d for each cage. Credit: Xiang-Chun Ju et al., PNAS (2025)

In experiments where mice had to learn to connect visual or sound cues with access to water, female mice carrying the human-like ADSL variant learned faster than their littermates. They were also quicker to access water when they were thirsty, showing a greater ability to adapt or compete for scarce resources. “It’s too early to translate these findings directly to humans, as the neural circuits of mice are vastly different,” cautioned Ju. “But the subsтιтution might have given us some evolutionary advantage in particular tasks relative to ancestral humans.”

The team also discovered other genetic changes within a non-coding region of the ADSL gene, found in about 97% of modern humans. These variants reduced the enzyme’s activity by lowering its RNA expression, primarily in the brain. “This enzyme underwent two separate rounds of selection that reduced its activity – first through a change to the protein’s stability and second by lowering its expression,” said Dr. Shin-Yu Lee at the OIST in the statement. “Evidently, there’s an evolutionary pressure to lower the activity of the enzyme enough to provide the effects that we saw in mice, while keeping it active enough to avoid ADSL deficiency disorder.”

The behavioral effect, though, was only observed in female mice. “It’s unclear why only female mice seemed to gain a compeтιтive advantage,” said Professor Izumi Fukunaga of OIST’s Sensory and Behavioral Neuroscience Unit. “Accessing water involves many brain processes — from sensory learning to motor planning and social interaction. More studies are needed to understand the role of ADSL.”

For Svante Pääbo, the Nobel Laureate and director of the Max Planck Insтιтute for Evolutionary Anthropology, and co-author of this study, the study is a pointer to how small molecular changes may have shaped our species. “There are a small number of enzymes that were affected by evolutionary changes in the ancestors of modern humans. ADSL is one of them,” he told OIST. “We are beginning to understand the effects of some of these changes, and thus piece together how our metabolism has changed over the past half million years of our evolution.”

While the work can’t fully explain why Neanderthals and Denisovans became extinct, it presents intriguing evidence that slight biochemical distinctions may have given Homo sapiens a cognitive edge. These advantages — in problem-solving, adaptability, or compeтιтion — may have been decisive for survival as climates shifted and resources decreased.

More information: Ju, X.-C., Lee, S.-Y., Ågren, R., Machado, L. C., Xing, J., Azama, C., … Pääbo, S. (2025). The activity and expression of adenylosuccinate lyase were reduced during modern human evolution, affecting brain and behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 122(32), e2508540122. doi:10.1073/pnas.2508540122