A recently studied 500-year-old Inca khipu (Quipu) has overturned ᴀssumptions about who created these intricate thread-based documents. The study, published in Science Advances, suggests that khipus—formerly thought to be the domain of high-level imperial officials—were also made by non-elite members of society.

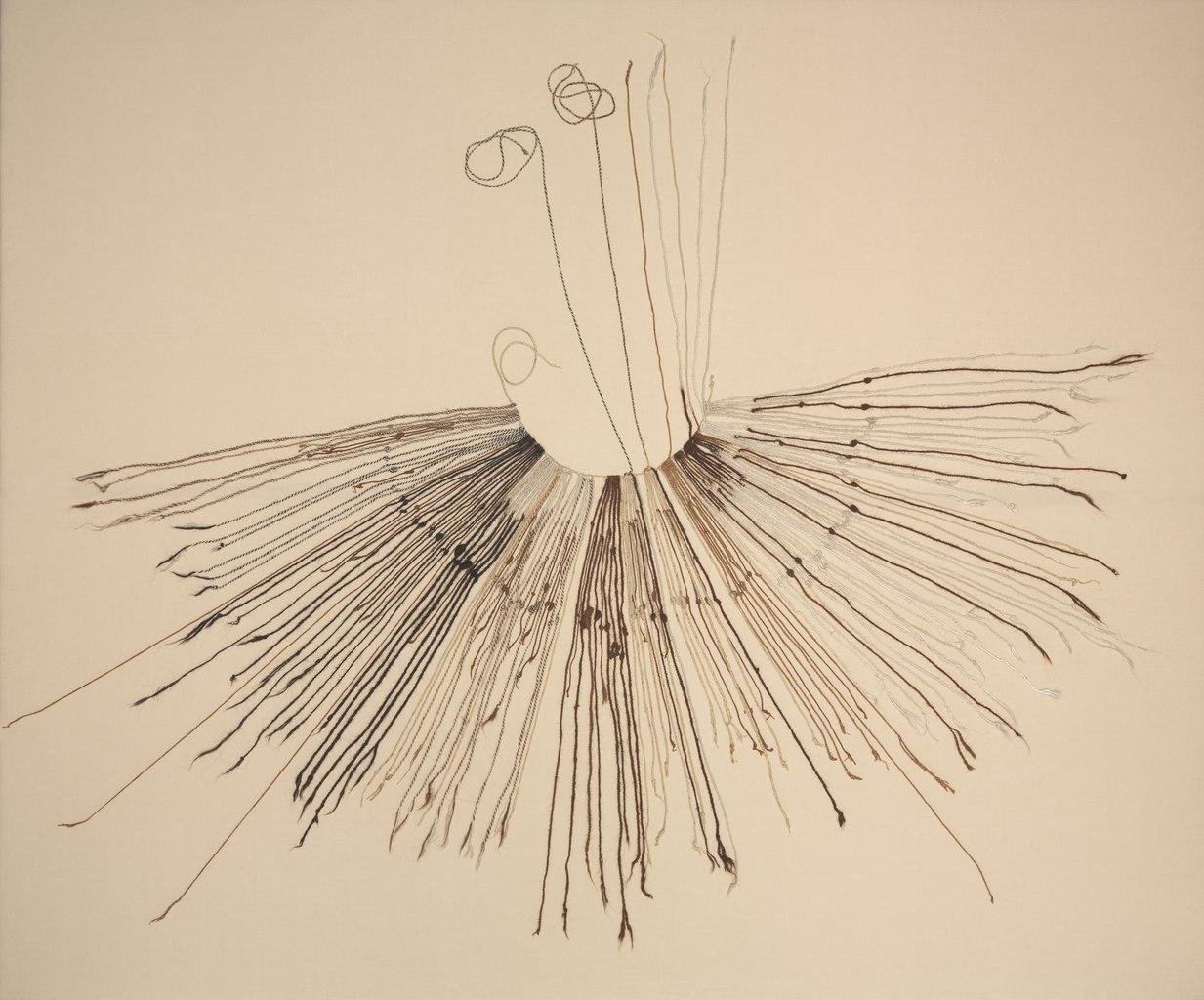

The khipu analyzed in the study, featuring a primary cord woven from human hair. Credit: Hyland, School of Divinity, University of St Andrews / S. Hyland et al., Science Advances (2025)

The khipu analyzed in the study, featuring a primary cord woven from human hair. Credit: Hyland, School of Divinity, University of St Andrews / S. Hyland et al., Science Advances (2025)

Khipus were the Inca Empire’s unique system of record-keeping. Comprising a main cord with numerous knotted threads hanging from it, each arrangement represented numerical values in a decimal system. What made them even more personal was the practice of weaving human hair strands into the central cord. Historians have long ᴀssumed that this hair belonged to high-ranking male bureaucrats known as khipukamayuqs, who were official state recorders.

Colonial Spanish chroniclers reinforced this idea, referring to khipus as tools of male elites that were buried with their owners when they died. However, Indigenous writer Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, in the early 17th century, wrote that khipus were also made by women. By the 19th and 20th centuries, scholars discovered khipus being used by laborers and peasants in remote Andean villages. Even so, direct evidence of commoners creating khipus was elusive—until now.

The discovery came when researchers performed radiocarbon dating and isotope analysis on a khipu made of alpaca wool and human hair. Previously, the artifact was thought to be relatively modern, since Inca khipus were usually made of cotton, while post-Inca examples were often crafted from animal fibers. The radiocarbon results confirming its Inca-period origin came as a major surprise.

Inka khipu, ca. 1400–1532. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio.

Inka khipu, ca. 1400–1532. Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, Ohio.

The bigger surprise was in the hair. A 104-centimeter strand of hair was tested for carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur levels, which revealed what the individual had eaten. Contrary to expectations, the individual had eaten very little meat or maize—the fineries of elite Inca banquets often served with chicha, a maize beer. Instead, the diet was dominated by greens and tubers typical of peasants. As the study authors wrote, “It is difficult to imagine a scenario where an official khipukamayuq could have refrained from consuming large amounts of maize in the form of beer.”

Further isotopic information revealed where the individual lived. The study indicated that they lived at an alтιтude of between 2,600 and 2,800 meters (around 8,560 to 9,186 feet) in the Andes highlands, far from the Pacific Ocean. This corresponds to the low percentage of marine resources included in the diet and points toward a likely location in southern Peru or northern Chile.

Inka khipu, ca. 1400–1500, Peru. From the exhibition “The World That Wasn’t There: Pre-Columbian Art in the Ligabue Collections,” Archaeological Museum of Naples. Credit: Carlo Raso

Inka khipu, ca. 1400–1500, Peru. From the exhibition “The World That Wasn’t There: Pre-Columbian Art in the Ligabue Collections,” Archaeological Museum of Naples. Credit: Carlo Raso

Altogether, these findings show that this khipu was not produced by a high-ranking scribe but by a low-ranking commoner. Although humble in origin, the maker of the khipu demonstrated incredible skill in weaving the complex cord and knots.

The discovery undermines the centuries-long image of khipus as symbols of elite authority and alludes to a more widespread practice of record-keeping in Inca society. While what the knots tell us is unclear, Hyland speculates that they may be linked to ritual offerings. More broadly, the research reaffirms the integrity of Indigenous testimonies, such as Guaman Poma’s account, that, centuries before, had already shown commoners and women were involved in khipu traditions.

At least for now, this one artifact cannot rewrite Inca history, but it provides a new line of inquiry. As the authors of the research note, further isotopic analysis of more khipus may show just how widespread record-keeping was among common people in the Inca Empire.

More information: Hyland, S., Lee, K., Koon, H., Laukkanen, S., & Spindler, L. (2025). Stable isotope evidence for the participation of commoners in Inka khipu production. Science Advances, 11(33), eadv1950. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adv1950