Archaeologists excavating in southwestern Kenya have uncovered strong evidence that early hominins were transporting stones over long distances about 2.6 million years ago—hundreds of thousands of years earlier than previously believed. The evidence, recently published in Science Advances, indicates that Oldowan tradition toolmakers not only produced convenient tools but also deliberately transported raw materials from up to 13 kilometers (roughly eight miles) to processing locations.

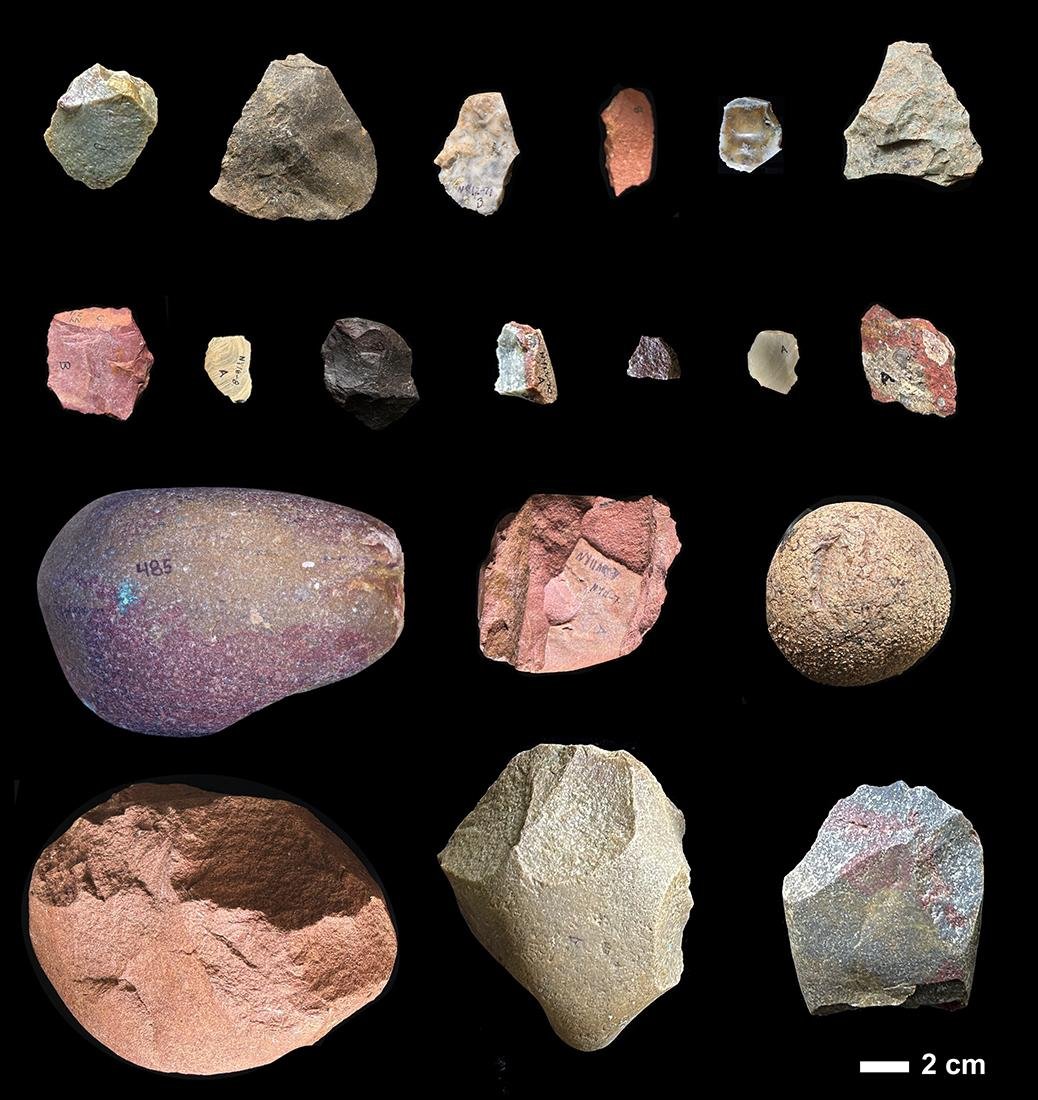

Oldowan stone tools made from a variety of raw materials sourced more than 6 miles away from where they were found in southwestern Kenya. Credit: E.M Finestone, J.S. Oliver, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project

Oldowan stone tools made from a variety of raw materials sourced more than 6 miles away from where they were found in southwestern Kenya. Credit: E.M Finestone, J.S. Oliver, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project

The discovery is from Nyayanga, a site on the Homa Peninsula that juts into Lake Victoria. Excavations there over the last decade have yielded hundreds of stone tools along with hippopotamus butchered remains. Scientists say the artifacts mark a cognitive leap in planning and use of landscapes by early hominins.

“People often focus on the tools themselves, but the real innovation of the Oldowan may actually be the transport of resources from one place to another,” said Rick Potts, the senior author of the study and director of the Smithsonian’s Human Origins Program, in a statement from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History. “The knowledge and intent to bring stone material to rich food sources were apparently an integral part of toolmaking behavior at the outset of the Oldowan.”

The Oldowan industry, the earliest sustained tool-making industry, allowed hominins to pound plants, cut meat, and scrape wood. They began striking stone cores with hammerstones around three million years ago to produce sharp flakes—tools that could be used in a number of ways. But Nyayanga’s materials were too soft to make effective tools, so toolmakers had to bring in volcanic and metamorphic stones such as rhyolite and quartzite from miles away.

Nyayanga excavation site in July 2025. Tan and reddish-brown sediments are more than 2.6-million-year-old deposits where fossils and Oldowan tools are found. Credit: T.W. Plummer, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project

Nyayanga excavation site in July 2025. Tan and reddish-brown sediments are more than 2.6-million-year-old deposits where fossils and Oldowan tools are found. Credit: T.W. Plummer, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project

The transportation of stone is evidence of a potential for forward planning, mental mapping, and delaying gratification—abilities that were once thought to have emerged later in human evolution. While some animals, including chimpanzees, move stones short distances for specific purposes, the Nyayanga ᴀssemblage represents the earliest archaeological evidence of systematic long-distance transport.

To date, the oldest confirmed instance of such activity came from Kanjera South, another Homa Peninsula site dating to two million years ago. The Nyayanga finds push this timeline back at least half a million years.

An Oldowan flake that was found alongside a hippopotamus shoulder bone at a hippo butchery site excavated in Nyayanga. Credit: T.W. Plummer, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project

An Oldowan flake that was found alongside a hippopotamus shoulder bone at a hippo butchery site excavated in Nyayanga. Credit: T.W. Plummer, Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project

The idenтιтy of the toolmakers is unknown. Two Paranthropus teeth were found in Nyayanga excavations, and perhaps these robust hominins—with their strong jaws specialized for grinding tough foods—might have been behind it. But the tools are also consistent with the documented behaviors of early members of the genus Homo. “Unless you find a hominin fossil actually holding a tool, you won’t be able to say definitively which species was making which stone tool ᴀssemblages,” said Emma Finestone, lead author of the study and ᴀssociate curator of human origins at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. “But I think that the research at Nyayanga suggests that there was a greater diversity of hominins making early stone tools than previously thought.”

Thomas Plummer, an anthropology professor at Queens College and co-director of the Homa Peninsula Paleoanthropology Project, emphasized the larger significance. “Hominins were using stone tools for a variety of pounding and cutting tasks, including processing plant and animal foods and working wood,” he said. “The diversity of activities that involved stone tools suggests that even at this early stage of cultural development, stone tools enhanced the adaptability of the hominins using them.”

The study underlines that innovation throughout human history has always depended on the relocation of resources to meet adaptive challenges. As Finestone put it: “Humans have always relied on tools to solve adaptive challenges. By understanding how this relationship began, we can better see our connection to it today—especially as we face new challenges in a world shaped by technology.”

More information: Finestone, E. M., Plummer, T. W., Ditchfield, P. W., Reeves, J. S., Braun, D. R., Bartilol, S. K., … Potts, R. (2025). Selective use of distant stone resources by the earliest Oldowan toolmakers. Science Advances, 11(33), eadu5838. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adu5838