Researchers in northeastern Ethiopia have made a thrilling discovery of fossilized teeth that may belong to a new branch of humanity, shedding more light on a critical period in human evolution. The remains are between 2.8 and 2.6 million years old and were found at the Ledi-Geraru archaeological site in the Afar Region—a region already famous for earlier finds, like the oldest known human jawbone and some of the earliest stone tools.

A male Australopithecus afarensis model (left) at the Natural History Museum, Vienna — credit: Wolfgang Sauber / CC BY-SA 4.0 — and a reconstruction of an adult female Homo erectus (right) at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History — credit: Tim Evanson / CC BY-SA 2.0. Edit and composite by Archaeology News Online Magazine.

A male Australopithecus afarensis model (left) at the Natural History Museum, Vienna — credit: Wolfgang Sauber / CC BY-SA 4.0 — and a reconstruction of an adult female Homo erectus (right) at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History — credit: Tim Evanson / CC BY-SA 2.0. Edit and composite by Archaeology News Online Magazine.

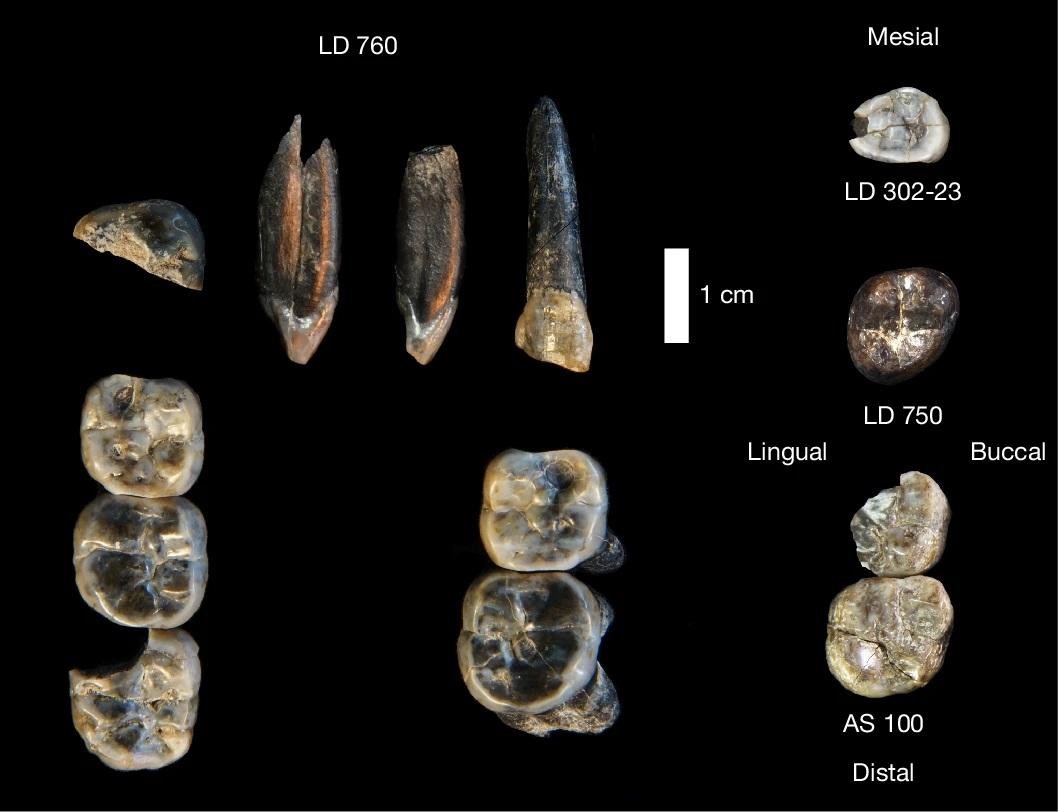

The 13 newly analyzed teeth belong to at least two early hominin lineages: one belonging to the genus Australopithecus—the same lineage as the renowned “Lucy” (A. afarensis)—and another belonging to the genus Homo, including modern humans (Homo sapiens). According to a study published in Nature, the Australopithecus fossils are of a different type from both A. afarensis and A. garhi, which suggests that there was a new, as-yet-unnamed species. “These specimens suggest that Australopithecus and early Homo existed as two non-robust lineages in the Afar Region before 2.5 million years ago,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers dated the fossils by analyzing volcanic ash layers above and below them. Ten Australopithecus teeth are about 2.63 million years old, two of Homo’s teeth are about 2.59 million years old, and another is about 2.78 million years old. The Homo teeth may belong to the same species as a 2.8 million-year-old jawbone already found at the site, but this is not yet confirmed, said co-author Kaye Reed.

The find paints a very diverse human family tree. Between three million and 2.5 million years ago, at least four different hominin lineages inhabited eastern Africa: early Homo, A. garhi, the newly identified Australopithecus found in Ledi-Geraru, and Paranthropus. Elsewhere, A. africanus occupied South Africa, and Paranthropus species lived in regions that are now Kenya, Tanzania, and southern Ethiopia.

Teeth from ancient hominins were unearthed at Ethiopia’s Ledi-Geraru archaeological site. Credit: B. Villmoare et al., Nature (2025) – (This image is used under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND license for non-commercial, educational, and informational purposes. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns regarding its use, please contact us for prompt removal.)

Teeth from ancient hominins were unearthed at Ethiopia’s Ledi-Geraru archaeological site. Credit: B. Villmoare et al., Nature (2025) – (This image is used under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND license for non-commercial, educational, and informational purposes. If you are the copyright holder and have any concerns regarding its use, please contact us for prompt removal.)

This contradicts the old narrative of human evolution as a linear, simple progression from ape-like ancestors to increasingly human-like forms. Instead, as paleoanthropologists emphasize, our evolutionary history is more like a bush with numerous branches—many of which ended in extinction.

The richness of the Ledi-Geraru site’s fossil record may be due to environmental factors such as volcanic activity that buried remains in ash. From animal fossils within the same layers, scientists deduce that the area was an open, arid grᴀssland. Geological data, however, suggest a more complex landscape 2.6–2.8 million years ago with rivers, vegetation, and shallow lakes that expanded and contracted over time.

Ledi-Geraru archaeological site. Credit: Ji-Elle / CC BY-SA 3.0

Ledi-Geraru archaeological site. Credit: Ji-Elle / CC BY-SA 3.0

The remaining question is how the early humans and their relatives lived together in the same range. Modern great apes, like chimpanzees and gorillas, tend to live in separate ranges rather than together. The researchers plan to study the chemistry of the enamel of the teeth to see what each species was eating, and this could reveal whether they were competing for the same resources or living in separate ecological niches.

Although the new Australopithecus fossils remain unnamed, their distinctive dental morphology strongly suggests a unique species. Even so, as paleoanthropologists say, more complete fossil evidence is required to give a new species a name.

For now, the find gives us a glimpse into a pivotal time in human evolution—an era in which multiple human-like species inhabited the African landscape simultaneously, adapting to changing environments and leaving behind evocative records of our shared heritage.

More information: Villmoare, B., Delezene, L.K., Rector, A.L. et al. (2025). New discoveries of Australopithecus and Homo from Ledi-Geraru, Ethiopia. Nature. doi:10.1038/s41586-025-09390-4