Archaeologists have unearthed new evidence that Pompeii, the ancient Roman city that was buried when Mount Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE, was reoccupied for centuries following the disaster, though it never regained its former splendor.

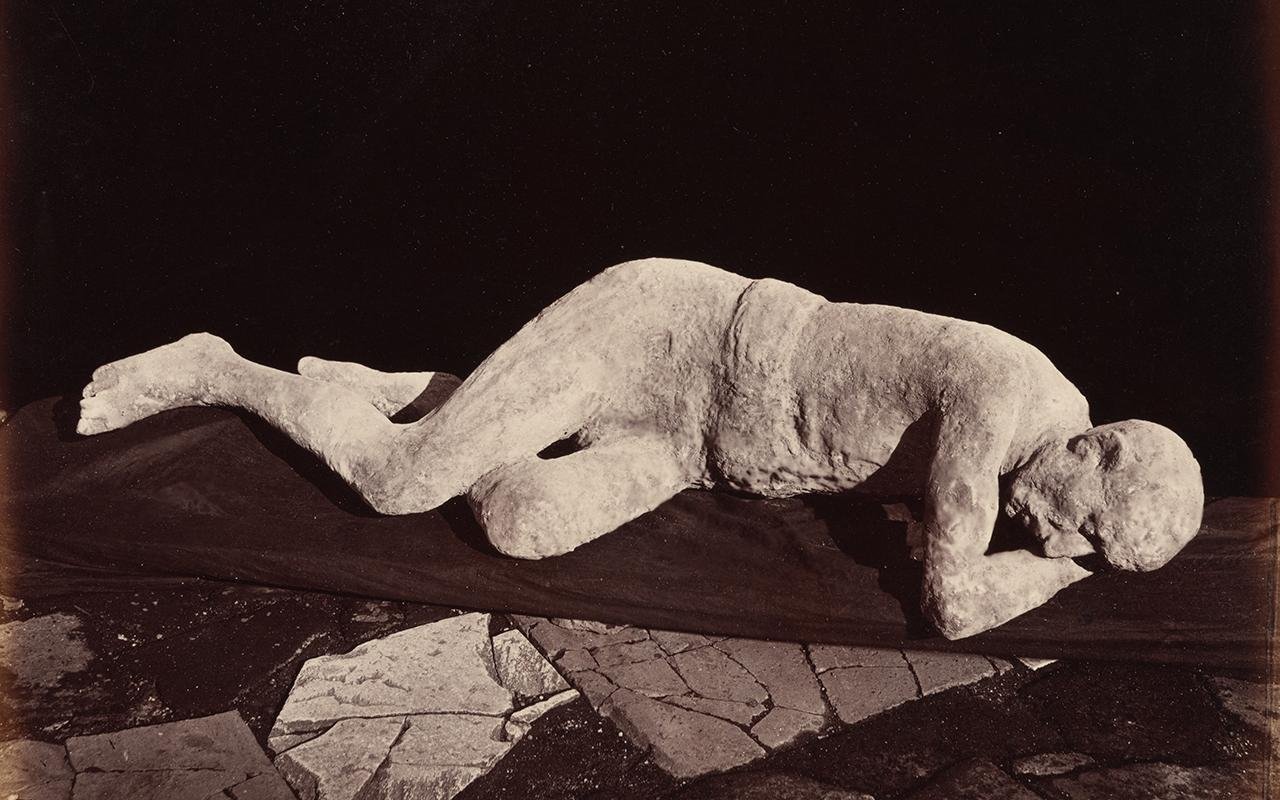

Human cast, Pompeii. A victim of the 79 CE Mount Vesuvius eruption, preserved in ash. Public domain

Human cast, Pompeii. A victim of the 79 CE Mount Vesuvius eruption, preserved in ash. Public domain

The finds are from recent excavations in the Insula Meridionalis, the southern quarter of the city, running from the Villa Imperiale to the Quadriportico dei Teatri. This area, partially excavated by the “Great Pompeii Project” (2012–2023), is now the location of a comprehensive program of safety, consolidation, and restoration. Concurrent with this, stratigraphic excavation has uncovered extensive evidence of life after 79 CE—features that earlier excavations often removed in the rush to expose the city as it was at the moment of destruction.

Prior to the eruption, Pompeii had a population of approximately 20,000. The number of deaths, though still the subject of some controversy, is estimated by archaeologists at 15–20% of the population, primarily due to thermal shock. Some of the survivors who could not start anew elsewhere returned to the destroyed city. They were later joined by newcomers—many of low social standing—lured by the opportunity to occupy abandoned villas or search for valuables buried under the ash.

Excavations suggest that people initially occupied the upper floors of buildings jutting out over the ash, with lower buried floors being repurposed to serve as cellars. The large vaulted spaces in the earlier horrea (warehouses) were subdivided into small rooms, ovens were built for bread baking, and staircases were constructed to access upper windows. Evidence of food production, including a millstone and another oven built inside a reused cistern in the House of the Geometric Mosaics, indicates a subsistence economy.

A beautifully crafted decorative relic uncovered in the recent excavations of the Insula Meridionalis. Courtesy of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii

A beautifully crafted decorative relic uncovered in the recent excavations of the Insula Meridionalis. Courtesy of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii

Archaeologists also recovered ceramics, coins from successive emperors, and even fifth-century oil lamps bearing the Chi-Rho monogram, indicating two main phases of resettlement: one from the late first to early third centuries CE, and another from the fourth to mid-fifth century. One poignant discovery was the burial of a newborn dated to between 100 and 200 CE.

They also found ceramics, coins of successive emperors, and even fifth-century oil lamps bearing the Chi-Rho monogram, testifying to two main phases of reoccupation: one in the late first to early third centuries CE, and the other in the fourth to mid-fifth century. Among the finds was the burial of a newborn dated to between 100 and 200 CE.

View of Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius. Credit: ElfQrin / CC BY-SA 4.0

View of Pompeii and Mount Vesuvius. Credit: ElfQrin / CC BY-SA 4.0

Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Pompeii Archaeological Park, clarified that earlier research often overlooked such remnants because the momentous episode of the city’s destruction in 79 CE has monopolised public memory. This neglect, he argued, created an “archaeological unconscious” where post-eruption Pompeii was largely invisible.

Ancient authors, including Suetonius and Cᴀssius Dio, confirm that two former consuls were commissioned by Emperor тιтus to oversee the city’s reconstruction with funds drawn from the estates of victims who died without heirs. Yet, despite imperial support, the settlement never regained the infrastructure, public architecture, or vitality of a true Roman city.

By the time of another eruption in 472 CE—just before the fall of the Western Roman Empire—Pompeii’s final residents abandoned the site. Today, a third of the 22-hectare UNESCO World Heritage site remains buried, but the new findings add a crucial chapter to its history: a story not only of catastrophic destruction, but also of resilience, adaptation, and survival among the ruins.

More information: E-Journal of the Excavations of Pompeii