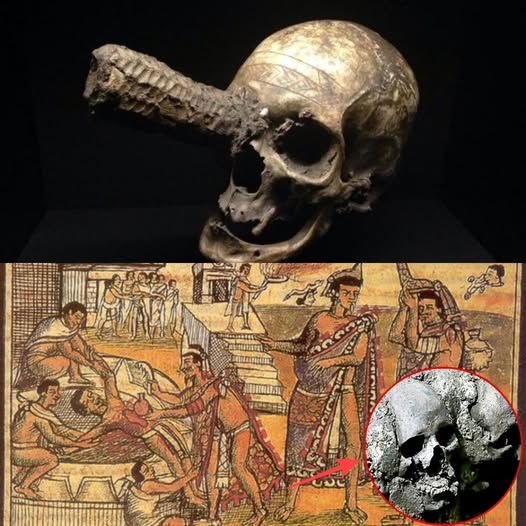

In the year 1999, in a dusty museum basement in Veracruz, Mexico, archaeologist Dr. Lucia Morelos wiped the fog from her glᴀsses and stared in disbelief. Resting atop a weathered storage crate, partially hidden under brittle linen, was an object that defied logic and rewrote boundaries between myth and reality. It was a human skull — unmistakably ancient, yet pierced through the cranium by what appeared to be a horn, or possibly a serrated stone appendage embedded deep into the bone.

The horn was not ornamental, nor surgically placed in modern times. CT scans and carbon dating would later confirm what her instinct already told her: this person, likely male and in his early 30s, had lived—and died—with this object driven cleanly through his skull, the bone healed partially around it. It wasn’t an execution; it was survival… followed by sacrifice.

Dr. Morelos had uncovered something far older than the Aztecs. The skull, along with accompanying artifacts, was estimated to be nearly 2,700 years old. The site it came from, buried under layers of colonial construction, was once a ceremonial precinct of a lesser-known pre-Maya culture called the Otomac. Until now, they had been little more than a footnote in Mesoamerican anthropology — seen as a nomadic, fragmented people with no written language, absorbed and erased by larger empires. But this skull — and the codex fragments found near it — told a different story.

Beneath the skull’s resting place were murals — or what remained of them — depicting men in elaborate robes holding curved obsidian knives, leading captives up stone steps. Blood was not just spilled; it was collected, channeled, and offered to towering effigies with open mouths. One figure in particular appeared again and again — a deity with spiral horns and an elongated skull, painted in crimson and ochre, always demanding blood. Some local historians whispered the name in Nahuatl: Tezcatlhuatl, the “Horned Mirror of Sacrifice.”

The most haunting image was carved in limestone: a figure kneeling, head tilted to the heavens, while a jagged spike was driven into his skull from above. His mouth was open, not in agony, but ecstasy. Around him, priests bowed in reverence, as if witnessing not a death, but a transformation.

Lucia remembered that night clearly — the air heavy with incense, the museum’s power temporarily lost due to a storm outside. Only her flashlight illuminated the horned skull. She felt not fear, but awe, as if the skull itself pulsed with dormant memory. What kind of world had this man lived in? What beliefs compelled him to endure such a brutal rite?

According to the few surviving Otomac glyphs, this was not an execution method, but a form of transcendence — a rare and honored path where warriors, chosen through dreams and hallucinogenic visions, allowed themselves to be “opened” to the gods. The horn, carved from fossilized coral and sharpened over decades, symbolized the World Spine — the link between the underworld, the earth, and the stars.

Skulls like this were not discarded. They were preserved in obsidian altars, pᴀssed from priest to priest like holy relics. The fact that this one had survived — intact, buried alongside ceremonial jade and etched bone — suggested it belonged to someone of immense spiritual importance.

And yet, what haunted Lucia most wasn’t the physical artifact, but the emotion it stirred. A sense of reverence. Not dread, but devotion. Could she, in her rational, scientific mind, accept that these people believed — truly believed — that pain opened portals?

The second discovery came three months later, when Dr. Morelos was granted access to a restricted section of a Spanish colonial crypt. There, hidden behind a false wall, lay another mural. This one was Christianized, with angels and flames and devils. But in the center stood a man, arms raised, and from his skull emerged a horn of fire — or light — stretching toward the heavens. Below him, ancient symbols not of Christianity, but of pre-Columbian design, wove between Latin inscriptions like veins through flesh.

A fusion. A forgotten syncretism. Perhaps even a survival.

The implications were immense. It meant that despite conquest, genocide, and forced conversion, the blood rites of the Otomac — or at least the memory of them — had bled into the colonial subconscious. Perhaps the “demonic” drawings condemned by the Inquisition were echoes of these earlier initiations.

That night, Lucia did not sleep. She stared out the window at the moonless sky, imagining the silent chants of forgotten priests, the flicker of torchlight on obsidian altars, and the unwavering eyes of the horned skull staring back through centuries. What did it mean to believe so deeply in transformation that you offered your skull to the gods?

She wondered, too, about the line between history and myth. About how many other “legends” were dismissed because they did not fit modern frameworks. Did the Otomac truly believe that the horn, when inserted during sacred ceremony, allowed visions of other realms? That the one who bore it would become not just a priest, but a living conduit for the divine?

Modern neuroscience might scoff — but Lucia recalled recent studies suggesting altered consciousness during extreme trauma or sensory overload. Were the Otomac practicing early neurosurgery… or something else entirely?

In the years that followed, Dr. Morelos published her findings, but not all of them. Some details she kept for herself — not out of fear, but respect. She had become a quiet guardian of the artifact, visiting it often, speaking softly in both Spanish and Nahuatl. Not praying, not exactly. But listening.

Visitors to the museum walk by the horned skull behind its glᴀss case every day, many never realizing what they’re seeing. Children gawk, tourists take pH๏τos, some joke nervously. But now and then, someone stops. They lean in. Their brow furrows. They stare — as if the ancient eyes, long turned to bone, still hold secrets worth remembering.

Lucia always notices those few. And she wonders… are they remembering something too?

We like to believe that our past is neat, categorized in museum labels and academic journals. But sometimes, it reaches out through time, messy and visceral, asking not to be understood, but felt.

This skull — with its cruel beauty and impossible story — is one of those echoes. And it asks a question not of science, but of the soul: