A new 3D digital analysis offers compelling evidence that the Turin Shroud—long believed by many to be the burial cloth of Jesus—was likely not created by contact with a real person’s body, but was actually crafted as a form of medieval religious art.

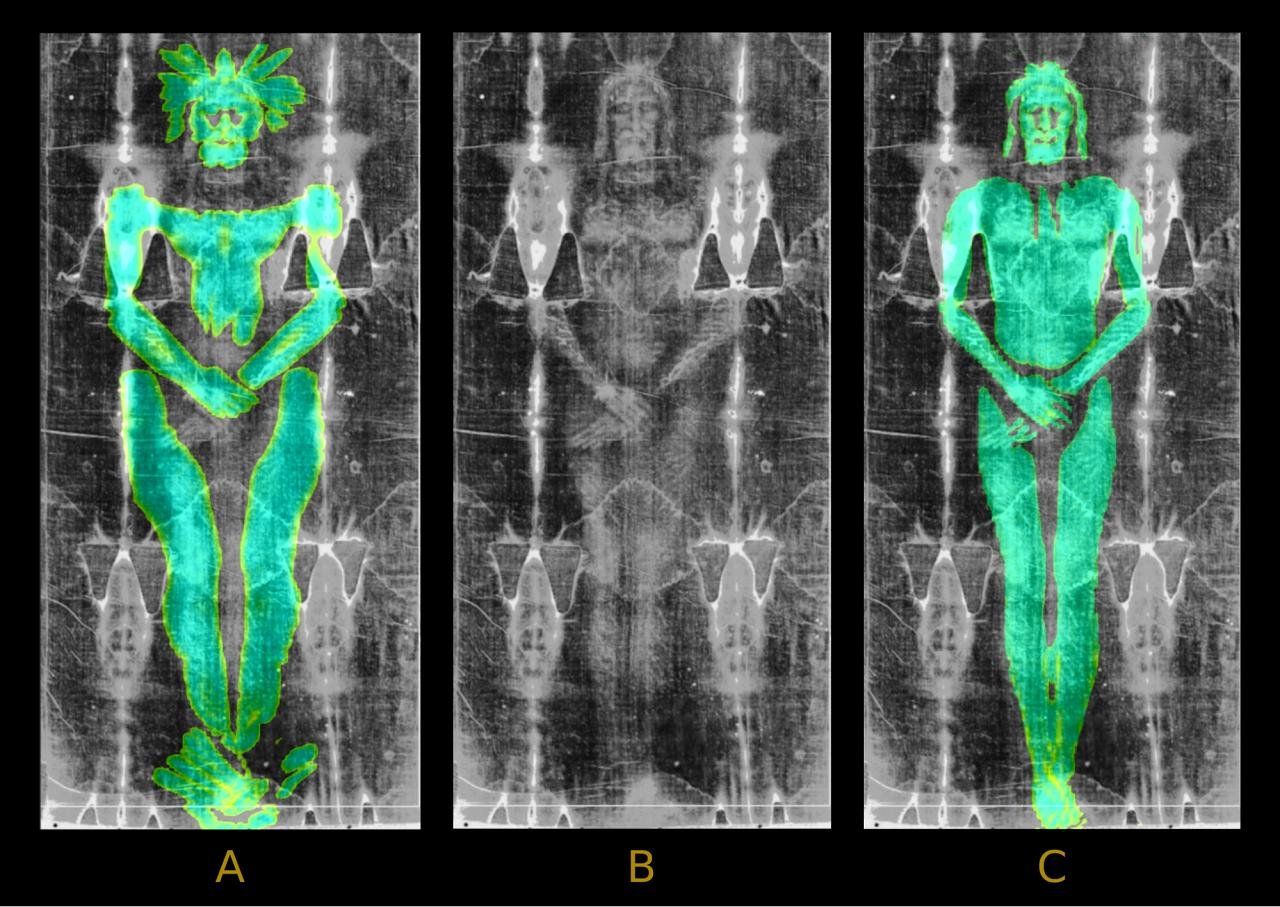

Touch texture in the three-dimensional model on the image of the shroud. B) Texture of the Shroud of Turin. C) Texture of the model in low relief over the image of the shroud. Image courtesy of Cicero Moraes. Used with permission

Touch texture in the three-dimensional model on the image of the shroud. B) Texture of the Shroud of Turin. C) Texture of the model in low relief over the image of the shroud. Image courtesy of Cicero Moraes. Used with permission

Published in the journal Archaeometry, the study was carried out by Brazilian digital graphics expert and 3D designer Cicero Moraes. Using free modeling software such as MakeHuman, Blender, and CloudCompare, Moraes modeled how clothing would move on two types of forms: a full three-dimensional human body and a low-relief sculpture—a flat surface with shallow, raised areas.

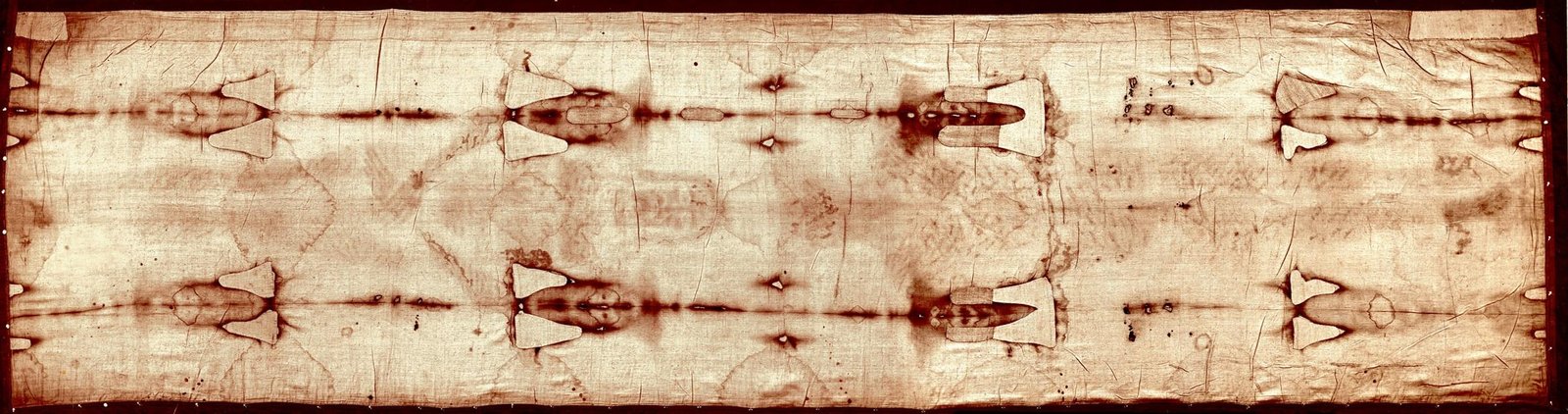

The Turin Shroud, measuring 14.5 feet by 3.7 feet, contains a faint image of a man with wounds that appear to be from crucifixion. It has been ᴀssumed for centuries that it wrapped the body of Jesus when he died over 2,000 years ago. Controversy, however, has surrounded its origins since the cloth first appeared in the 14th century. A 1989 radiocarbon dating test placed the origins of the shroud between 1260 and 1390 CE, in the medieval period. While later researchers disputed those findings, suggesting that the sample had possibly come from a repaired section of the cloth, the issue remains unresolved.

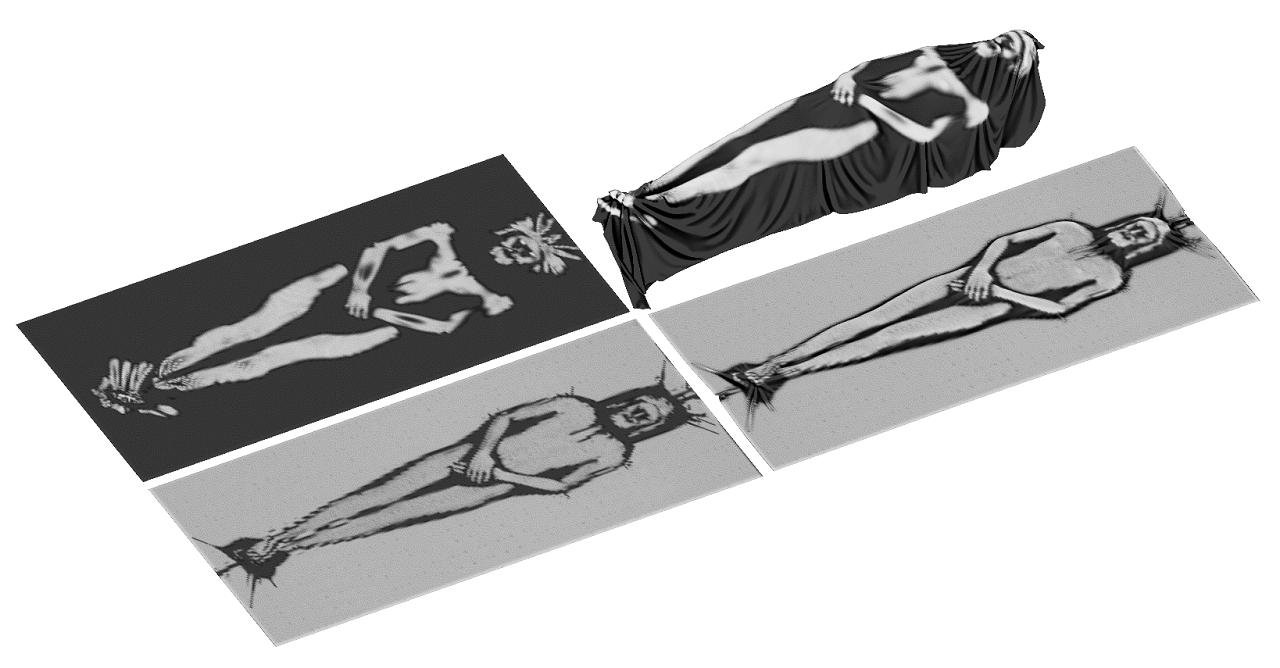

Comparison between the 3D model and low relief, lateral orthographic view. Image courtesy of Cicero Moraes. Used with permission

Comparison between the 3D model and low relief, lateral orthographic view. Image courtesy of Cicero Moraes. Used with permission

In Moraes’s recent digital test, the image that was produced when a cloth was virtually draped over a 3D human model appeared warped—wider and misshapen—due to the nature of fabric flowing over volume. That distortion is called the “Agamemnon Mask effect,” named after the wide gold funerary mask discovered at Mycenae, an ancient Greek archaeological site. On the other hand, the imprint from a low-relief sculpture closely matched the shape and dimensions of that on the Turin Shroud.

The Shroud of Turin: modern pH๏τo of the face (left) and digitally enhanced image (right), created using digital filters. Credit: Dianelos Georgoudis / CC BY-SA 3.0

The Shroud of Turin: modern pH๏τo of the face (left) and digitally enhanced image (right), created using digital filters. Credit: Dianelos Georgoudis / CC BY-SA 3.0

“The contact pattern generated by the low-relief model is more compatible with the Shroud’s image,” Moraes wrote in the study. “It shows less anatomical distortion and greater fidelity to the observed contours.”

He described how a shallow sculpture, maybe made of wood, stone, or metal, would be a strong candidate to serve as a mold. Heat or pigment may have been applied only to the embossed areas of the surface to create an imprint on the fabric. This way, Moraes contended, this method would explain the smooth, flat image one finds on the Shroud, unlike the distorted result one might find by wrapping fabric around a real human body.

Full-length image of the Turin Shroud before the 2002 restoration. Credit: Giuseppe Enrie, 1931

Full-length image of the Turin Shroud before the 2002 restoration. Credit: Giuseppe Enrie, 1931

Moraes highlighted that while it remains remotely possible that the image might have originated from a real body, the evidence supports the view that the Shroud was an artistic creation. He did not explore the actual material and process used, but concluded that the artifact must be interpreted as best being a funerary object and a “masterwork of Christian art.”

This artistic representation is in keeping with the time. During the medieval period, low-relief depictions of religious individuals—particularly on tombstones—were common in Europe. Shallow carvings would have been a familiar practice to artists during this time.

While Moraes’s study does not attempt to answer the mystery of the Shroud’s age, it does cast new light on the manner in which the image might have been formed.

His findings do not disprove a religious interpretation but offer a scientific view of one of the world’s most enigmatic religious relics. Regardless of whether a medieval forgery or sacred relic, the Shroud of Turin is a persistent symbol—and a mystery that modern technology continues to investigate.

More information: Moraes, C. (2025). Image formation on the holy Shroud—A digital 3D approach. Archaeometry. doi:10.1111/arcm.70030