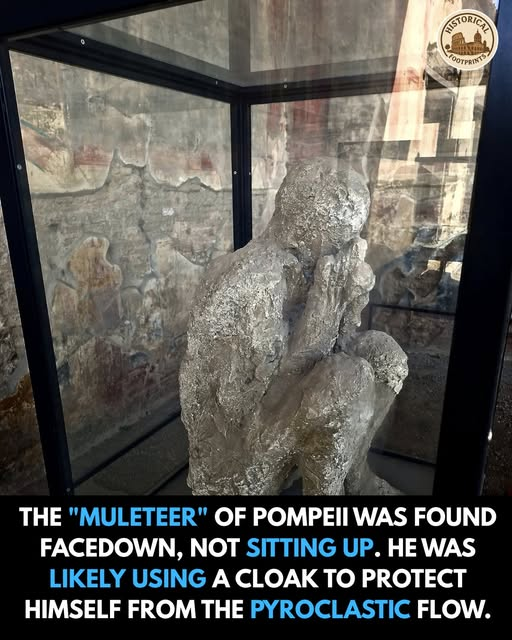

The room was quiet, save for the muffled hum of tourists wandering nearby and the faint tap of rain on the museum’s glᴀss ceiling. Inside the black-framed display stood a figure, curled in eternal stillness—arms raised to shield his face, body hunched in a silent act of desperation. He was not standing, not reclining in peace, but folded inward like a soul bracing for the sky to fall.

They called him the Muleteer.

And though his name, his face, and his life were lost to time, his death—the posture of his final moment—was immortalized in ash.

It happened on a morning that began like any other. The year was 79 CE, and life in Pompeii was vibrant. Streets bustled with chatter, fountains trickled over marble, and bakers prepared fresh loaves in ancient ovens still warm from the night before. The city, nestled beneath the shadow of Mount Vesuvius, had thrived in ignorance of the danger above. Rumblings had occurred, yes—but the volcano had slept for so long that few remembered it could wake.

The Muleteer—no one knows his real name—was likely a laborer, perhaps guiding pack animals through the cobbled roads, delivering goods between villas and vineyards. Some say he might’ve been a merchant’s ᴀssistant. Others believe he was a simple traveler, pᴀssing through. But what’s certain is this: when Vesuvius erupted, he had nowhere left to go.

The eruption was sudden and cataclysmic.

Vesuvius tore itself open, launching a column of ash twenty miles into the sky. By the afternoon, darkness fell over Pompeii like a shroud. Buildings collapsed under the weight of falling debris. Roofs caved in. People choked on the ash, their screams muffled by clouds of death. But the worst was yet to come.

Just after dawn the next day, a pyroclastic surge—a roaring wall of superheated gas and volcanic rock—swept through the city at hurricane speeds. It moved fast enough to turn bone to dust. Flesh burned in an instant. And yet, in that frozen second, the Muleteer tried to live. Or at least, tried not to die.

Archaeologists found his remains centuries later, not sitting calmly, as early plaster casts suggested, but lying facedown. His arms, lifted as if pulling a cloak over his head, told a story of frantic instinct. A man protecting himself from fire. From heat. From a sky turned into a weapon.

Plaster casts like his were the invention of 19th-century archaeologist Giuseppe Fiorelli. When excavators noticed hollow spaces in the ash—imprints of vanished bodies—they poured liquid plaster into them. What emerged were haunting statues of the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ: men, women, children, and even animals, forever locked in their final poses. The Muleteer was one of them.

But his form was different.

More intimate.

More human.

To stand before his cast today is to feel time collapse.

You don’t see a statue.

You see a man—a real man—caught in a storm of fire, clinging to the most human instinct of all: to live, even when life is already gone.

He wasn’t a soldier. He wasn’t a king. He left no scrolls, no names carved into stone. His only monument is his death, shaped by fear, frozen by fate. And yet, somehow, it says more about the fragility of existence than any emperor’s tomb.

Historians debate his role, his age, even his clothing. Was that shape around his shoulders really a cloak? Some believe it was a pack, others a woolen wrap he pulled тιԍнт against the searing air. Perhaps he carried goods—tools, food, letters—that were meant for someone waiting at the edge of town, now also lost in ash. Or maybe he was just trying to return home.

What makes the Muleteer so heartbreaking is not just that he died.

It’s that he fought death in that final instant.

Even as the surge came roaring down the mountain—H๏τter than any fire, faster than any wind—he chose not to kneel, not to surrender. He raised his arms. He curled inward. And in that small gesture, his story remained.

The preservation of Pompeii is a miracle born of tragedy. The city was entombed so swiftly that entire rooms remained intact—bottles on shelves, murals on walls, coins in pockets. But while its architecture survived, it is the people—those ash-filled silhouettes—that resonate most deeply.

Each figure tells a story: the lovers entwined in the Garden of Fugitives, the mother clutching her child, the dog twisted in agony, chained beside a doorway. But the Muleteer’s pose is uniquely haunting. He did not fall to the ground limply. He didn’t try to flee. He prepared for impact. He resisted, if only for a second.

Visitors often ask: was he in pain?

Scientists believe the heat was so intense—up to 300°C (572°F)—that death came instantly. Muscles tensed in a final spasm. Blood boiled. Bones fractured from thermal shock. But in that split second, the brain might still have been aware. Might still have known fear. Might still have hoped, irrationally, that covering his face could keep the flames away.

It is that hope—illogical, instinctual, painfully human—that lingers.

In many ways, the Muleteer represents all of us.

We go about our days, unaware of the invisible catastrophes waiting beyond the horizon. We believe we have time. We believe we have control. And when the unthinkable comes, we react not with grand gestures, but with small, human ones.

A hand raised.

A breath held.

A prayer whispered into heat and silence.

Over the years, the Muleteer has drawn artists, poets, scholars, and schoolchildren. They press their hands to the glᴀss. They lean in close. And whether they realize it or not, they’re not looking at death.

They’re looking at the last act of life.

A man trying to protect himself—not knowing it was futile, not knowing he would become a symbol, not knowing his story would echo for two thousand years.

And now, as the world spins faster, as disasters shift from fire to flood, from war to disease, his form feels more relevant than ever. He is not a relic. He is a reflection.

Of all of us.

Of what it means to face the unknown with nothing but instinct.

Of what it means to be human, even when humanity seems powerless.

So if you ever find yourself in Pompeii, walking those ancient roads, past the cracked mosaics and quiet ruins, visit the Muleteer. Stand before his glᴀss case. Take a breath. And remember:

He did not die silently.

He screamed through ash.

He hoped through fire.

And through that final act, he reached out across time, not with words, but with form.

To remind us that in the face of destruction, there is always a flicker of defiance.

Always a hand raised.

Always a heart beating one last time.

The Muleteer did not survive.

But his story did.

And in that story, we remember not just how people died in Pompeii—

But how, in their last moments, they lived.