A new study has unveiled incredibly detailed tattoos on a 2,500-year-old mummy unearthed in Siberia’s Altai Mountains, yielding unusual insights into the artistry, technology, and cultural significance of tattooing by Iron Age nomads. Using high-resolution near-infrared imaging, archaeologists have digitally reconstructed these ancient tattoos with unprecedented precision.

PH๏τogrammetrically created 3D model of the female mummy from Pazyryk tomb 5, showing: A) texture derived from visible-spectrum pH๏τographs; and B) texture derived from near-infrared pH๏τography (figure by M. Vavulin). Credit: G. Caspari et al., Antiquity (2025)

PH๏τogrammetrically created 3D model of the female mummy from Pazyryk tomb 5, showing: A) texture derived from visible-spectrum pH๏τographs; and B) texture derived from near-infrared pH๏τography (figure by M. Vavulin). Credit: G. Caspari et al., Antiquity (2025)

The mummy, a 50-year-old woman at the time of death, was part of the Pazyryk culture, a sixth-to-second-century BCE Iron Age society that lived on the Eurasian steppe. The Pazyryk were renowned for constructing mᴀssive burial mounds, or kurgans. They buried their deceased in chambers carved into permafrost, which preserved organic material such as skin and body art.

The research, published in the journal Antiquity, was conducted by Dr. Gino Caspari of the Max Planck Insтιтute of Geoanthropology. His team used advanced near-infrared digital pH๏τography with submillimeter precision to reveal tattoos that had faded over time. While some tattoos were discovered on Pazyryk mummies in earlier decades, their condition and limitations of imaging technology left few designs properly documented, or made most visible only in schematic sketches.

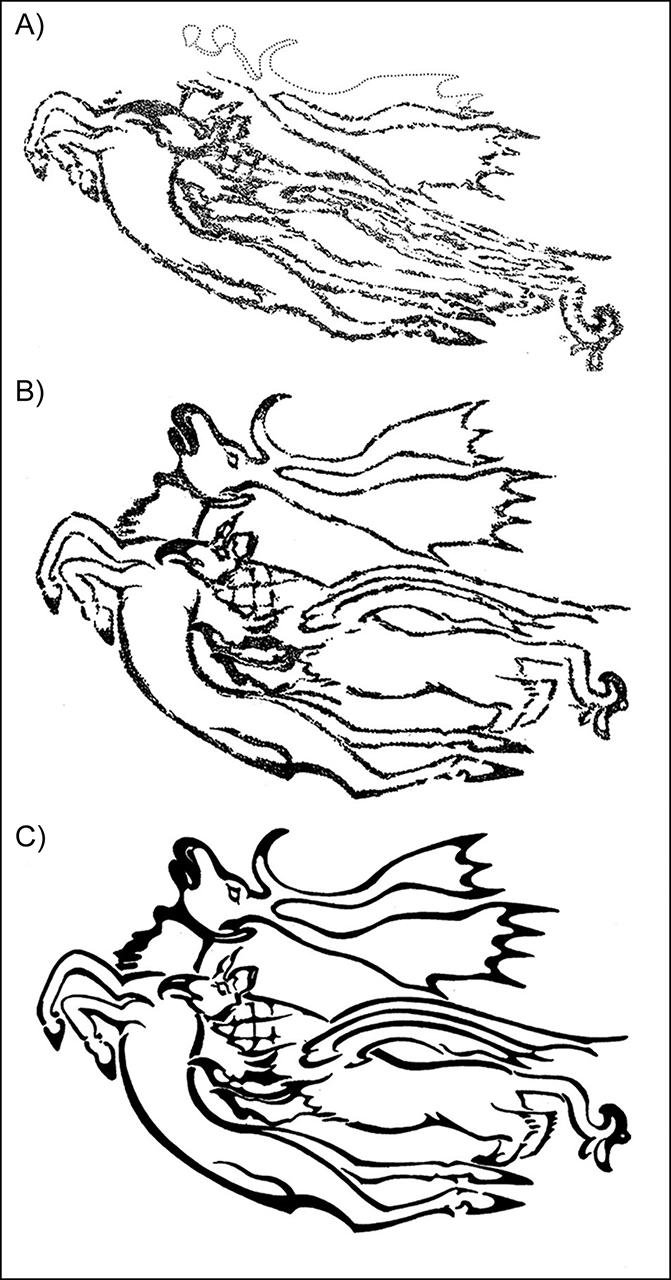

Now, sophisticated imaging has captured the entire extent of the tattoos. Among the images are a stag surrounded by leopards on the right forearm and a griffin beast battling a deer on the left arm. The designs are so fine that they have fascinated modern tattoo artists. According to Caspari, tattooing seems not only to have served as symbolic decoration but as a specialized art—one which demanded technique, aesthetic perception, and formal training.

Infrared light reveals an ancient tattoo and a postmortem suture, suggesting the art held no specific role in funerary rituals and may have lost its meaning after death (figure by G. Caspari & M. Vavulin). Credit: G. Caspari et al., Antiquity (2025)

Infrared light reveals an ancient tattoo and a postmortem suture, suggesting the art held no specific role in funerary rituals and may have lost its meaning after death (figure by G. Caspari & M. Vavulin). Credit: G. Caspari et al., Antiquity (2025)

The study uncovered striking contrasts between tattoos on each arm. The right arm features smooth lines and carefully placed motifs, suggesting they were completed in at least two separate sessions by an experienced artist. The left arm has less precise images, possibly the work of a novice or completed earlier in life.

To discover more about the techniques, the researchers collaborated with Daniel Riday, a tattoo artist who recreates ancient artwork using traditional tools. His examination indicated that the lines were created by single-point and multipoint hand-poking instruments. No tattooing tools have been found at Pazyryk burials, but the researchers believe they were made from organic materials like horn or bone. The pigment may have been soot or burnt plant matter. Riday further suggested the designs may have been stenciled on the body before being tattooed.

Right forearm tattoo: A) current state; B) deskewed, evening out skin folds and compensating for the desiccation process; C) idealised artistic rendering (illustrations by D. Riday). Credit: G. Caspari et al., Antiquity (2025)

Right forearm tattoo: A) current state; B) deskewed, evening out skin folds and compensating for the desiccation process; C) idealised artistic rendering (illustrations by D. Riday). Credit: G. Caspari et al., Antiquity (2025)

Despite the preservation, the majority of the tattoos had been cut during the embalming process. This led researchers to wonder whether, unlike some other ancient societies, the Pazyryk may not have held tattoos to be spiritually significant in the afterlife. Instead, body art likely existed to reflect status, personal idenтιтy, or membership in a group during life.

The new find allows archaeologists to look at ancient body modification practices not just as evidence but as the product of human hands, each of them with some level of skill, purpose, and intent.

The Altai Mountains’ frozen tombs, initially excavated in the 19th century and rediscovered by Soviet and international expeditions in the 20th century, remain among the best-preserved archaeological contexts for the study of ancient tattooing. However, scientists warn that the permafrost graves are deteriorating faster due to climate change; therefore, high-tech documentation is urgent.

Caspari’s team believes that by digitally preserving these tattoos and comparing them with experimental reconstructions, it may become possible to trace individual artists’ techniques and better understand the spread of tattoo traditions across ancient Eurasia.

More information: Caspari, G., Deter-Wolf, A., Riday, D., Vavulin, M., & Pankova, S. (2025). High-resolution near-infrared data reveal Pazyryk tattooing methods. Antiquity, 1–15. doi:10.15184/aqy.2025.10150