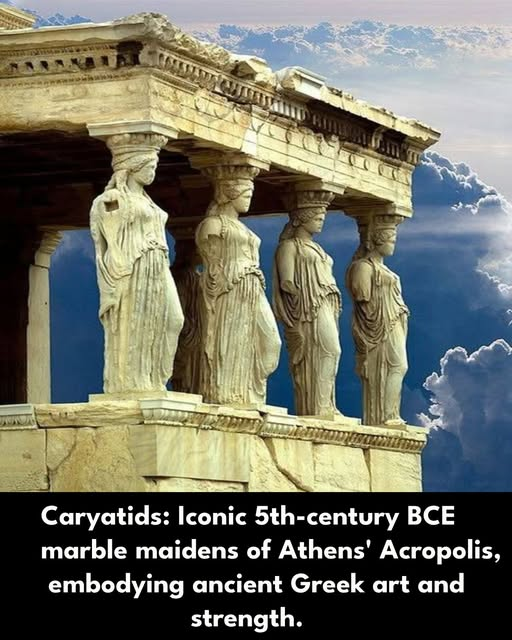

They stand not on a battlefield nor in a throne room, but beneath the sky, with their gaze fixed forever beyond the hills of Athens. They are not queens or goddesses, and yet they bear the weight of a temple roof upon their heads. They are the Caryatids — six marble maidens, frozen in graceful defiance, on the southern porch of the Erechtheion atop the Acropolis. And though their stone lips are sealed, their presence speaks across millennia — of beauty, burden, resistance, and remembrance.

To see them is to feel seen.

Built in the final decades of the 5th century BCE, the Caryatid Porch is perhaps one of the most hauntingly human architectural elements to survive from ancient Greece. Amid the Doric columns and stately ruins of Athens, these women are not anonymous supports; they are individuals — carved with care, draped in sculpted fabric that moves like wind through linen. They appear mid-thought, mid-step, as though interrupted by eternity. The subtle bend in a knee, the turn of a head — these are not just ornaments. They are symbols, anchors to a past where people lived, worshipped, and dreamed.

But who were they?

The name “Caryatid” stems from the women of Karyai, a village in Laconia. According to ancient accounts, the maidens of Karyai danced in honor of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. The mythos tells us that their elegance and discipline were so admired that architects chose to immortalize them in stone. But deeper layers suggest more sobering origins. One tale — perhaps Roman in embellishment — claims that after Karyai betrayed Greece to the Persians, its women were enslaved and forced to carry heavy burdens. Whether tribute or punishment, the truth has become buried beneath centuries of interpretation. What remains is the image: women made into pillars.

And yet — how different they are from mere columns.

Their hair is thick, intricately braided not just for beauty but for structural strength. Their robes, called peploi, fall in complex folds that mask their architectural function. Their faces are serene, detached from their labor. Each one is similar but subtly distinct, hinting that the sculptors — perhaps those under the direction of Phidias — imbued them with individuality. These are not copies, but characters. Sisters, perhaps, or priestesses, forever lifting what the world cannot see.

The Erechtheion, their temple, was no ordinary sanctuary. It was built to house sacred contradictions. Perched on uneven ground and split between levels, it was dedicated to both Athena and Poseidon, embodying the city’s most ancient myths. Here was the spot where Athena’s olive tree supposedly sprouted and where Poseidon’s trident struck the earth. It was also said to be the burial place of Erechtheus, an early king of Athens who was both man and myth. The temple had to accommodate mythic geography — and it did so with complexity and grace. The Caryatid porch, attached to the south side, offered not only visual balance but poetic counterweight to the structure’s sacred tension.

But history, like Athens itself, is no stranger to plunder.

In the early 19th century, during the age of imperial “collecting,” Lord Elgin — the British ambᴀssador to the Ottoman Empire — arranged for one of the Caryatids to be removed. She now stands, alone and out of place, in the British Museum. In her absence, a plaster copy fills the gap in Athens. For many Greeks, her removal is not just a matter of stolen art but of stolen idenтιтy. Imagine a family portrait where one face has been cut out. Her sisters wait still, gazing east, their lines softened by pollution, their souls bruised by longing.

But the Caryatids are not only artifacts — they are survivors.

They have weathered time, war, acid rain, earthquakes, and empires. In the late 20th century, conservationists took action. The remaining five originals were moved indoors to the Acropolis Museum, where they now stand under filtered light. Each bears the scars of centuries but also the fingerprints of their makers. With laser technology, restorers now clean them delicately, burnishing away the soot of the modern city to reveal the Pentelic marble’s original glow — a kind of luminous honey white, once painted, once alive with color.

And in their silence, they speak louder than ever.

Visitors to the museum often find themselves hushed in their presence. Children stare, women linger, and men grow quiet. There is something intimate about them — as if they are not just holding up a roof but holding onto something for us. Perhaps what they bear is not architectural weight, but cultural memory. The Caryatids remind us that beauty can be strength, and that dignity can exist even in burden. They also whisper the ancient truth: that civilization is a house built on the backs of many — often women — whose names we never learn.

They are not Aphrodite, goddess of love, nor Athena, goddess of war. They are something far more profound: anonymous excellence.

The power of the Caryatids lies in this ambiguity. They are not of myth, but of life. And yet they have become mythic. They are not royal, yet more revered than queens. They do not move, but they move us. The 19th-century Romantic poets saw in them the spirit of lost Greece. Feminist thinkers see in them the paradox of strength disguised as grace. Tourists see only statues — until they stand before them and feel something shift.

Even today, their image echoes across the world. From banks to balconies, from Paris to Washington, “caryatid” columns have become a motif, usually stripped of meaning. But the originals endure, far beyond ornament. They are a living metaphor — for resilience, for quiet power, for the way women have always upheld the weight of the world without complaint, without name.

And when the sun begins to fall over the Acropolis, casting long shadows across the marbled hill, their forms reanimate in gold and gray. For a fleeting moment, they are no longer sculpture, but memory made flesh. You can almost hear the murmur of prayers, the clink of oil lamps, the hush of sandaled feet. You can almost believe that the stone breathes.

In the end, the Caryatids are not just statues — they are a question: what do we choose to carry, and who carries it for us?