There is a place where the wind never forgets its name.

Perched on the southernmost edge of the Attic peninsula, where the land juts into the wine-dark Aegean, the Temple of Poseidon at Cape Sounion stands — or rather, endures. To arrive here is not just to visit a ruin, but to arrive at a threshold between earth and myth, between the mortal world and the vast, unknowable sea. The columns are bleached by sun and salt, weathered yet upright, like sentinels of memory. And though time has taken much, what remains is hauntingly beautiful.

But let us go back — far back, to when this temple was whole.

It was the 5th century BC, and Athens was awakening into its golden age. Philosophy, democracy, and the arts flourished. The scars of the Persian invasions were fresh, but pride was deeper still. The Athenians had emerged victorious, not only on land at Marathon but most gloriously at sea, at Salamis. And the sea, to the Greeks, was not just geography — it was destiny. It was trade, food, danger, and deliverance. It was also home to Poseidon, god of the deep, brother to Zeus, and wielder of the earth-shaking trident.

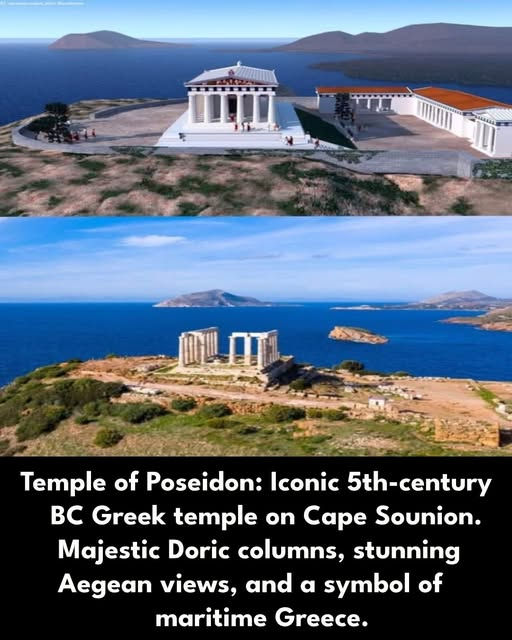

So, as an act of reverence — and perhaps appeasement — the Athenians raised a temple at the very edge of their world. At Cape Sounion, where ships departed and returned, where lovers wept farewells and kings watched for sails, they erected this shrine. Twenty-four Doric columns once held the structure high above the cliff, blinding white under Helios’ gaze, visible from great distances at sea. Sailors would spot it and know they were nearing home — or leaving it behind.

The temple itself was simple by design but powerful in symbolism. Doric columns, sturdy and no-nonsense, spoke of strength. Inside, a colossal bronze statue of Poseidon is said to have stood, commanding and unblinking, holding a trident in one hand and, perhaps, a dolphin in the other — an image both of wrath and mercy. Offerings were made here: wine, coins, the bones of bulls, and whispered prayers sent into the wind.

Archaeologists found the ruins in the 19th century and marveled not just at the remains, but at what the temple represented — a convergence of spiritual devotion and geopolitical importance. This was not an isolated monument; it was part of a defensive triangle with temples at Aegina and the Acropolis in Athens, forming a sacred network that also served a strategic eye on the sea.

But Cape Sounion’s stories are not built only from stone.

There is a legend tied to the temple, etched deep into the cultural psyche of Greece — the tale of Theseus and his father, King Aegeus. Theseus, young and proud, had sailed from Athens to Crete to slay the Minotaur. His father, standing watch at Sounion, had instructed him: if he returned alive, to change the sails from black to white. But Theseus, triumphant yet thoughtless, forgot. And so Aegeus, spotting black sails on the horizon, was overcome with grief. From this very cliff, he leapt into the sea — and that sea, ever since, has borne his name: the Aegean.

Stand at the cliff’s edge today and the wind still howls that tragedy.

Tourists come now, in buses and sandals, with selfie sticks and wide eyes. They lean on the roped barriers and look outward, perhaps without knowing what they’re feeling. It’s not just the view — though the view is staggering. It’s the sense of something larger. Of having arrived at a border between the human and the eternal.

You might meet a retired sailor from Piraeus, standing silently in the wind, cap in hand. Or a young bride taking her wedding pH๏τos in the golden light. Or a German poet scribbling verses in a notebook, overwhelmed by the silence. The Temple of Poseidon attracts many kinds — not just historians and archaeologists, but those seeking something they can’t name. Meaning. Awe. Peace. Closure.

And at sunset, oh, the sunset.

The light becomes honeyed, the sky washes in gradients of crimson and lavender, and the columns catch fire with gold. It is said that even Lord Byron, the Romantic poet, fell under its spell. He carved his name into one of the stones — a small act of vandalism, yes, but also an eternal gesture of reverence. He wrote later of “Greece and her ruins,” and nowhere do those words land heavier than here.

Today, the temple is protected, stabilized, and studied. Drones buzz above it, and virtual reconstructions — like the one you’ve seen — try to restore what time has dismantled. Digital archaeologists, armed not with trowels but algorithms, have given us a glimpse of what once was: the vivid red-and-white paint of the friezes, the clean lines of the columns, the geometry of belief turned into architecture. And yet, somehow, the ruin speaks louder than any reconstruction.

The erosion, the missing blocks, the ghostly presence of what was — these remind us that even greatness fades. But in that fading, something strange happens. The temple becomes more human. Not a monument to power, but to perseverance. To the urge, deep in the ancient soul, to build something that might outlast storms and sorrow.

You walk the site slowly, reverently, brushing your fingers against sun-warmed marble, conscious that a thousand hands before yours have done the same. You imagine the priests in linen robes, the sounds of lyres and sea gulls, the incense rising as a ship departed. You imagine a mother placing a wreath on the altar, whispering the name of a son sailing to war.

And then you look out, across the sea — and suddenly you’re not in the present at all.

You’re in a timeless moment, standing where fear and hope once met. The ancient Greeks built temples not just to house gods, but to confront them. To say: We are here. We know our place. But we will still build, still worship, still sail.

And so, the Temple of Poseidon, battered though it may be, becomes not just a relic, but a reflection. Of the human spirit. Of beauty forged in harsh places. Of our need to stand at the edge of the world and say: Remember us.