A new interpretation of 3,800-year-old inscriptions discovered in an Egyptian turquoise mine has reopened one of archaeology’s most controversial debates: Did Moses, the biblical leader of the Exodus, ever exist?

Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law (1659) by Rembrandt. Public domain

Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law (1659) by Rembrandt. Public domain

Independent researcher Michael S. Bar-Ron believes the answer lies in the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions carved into rock walls at Serabit el-Khadim, an Egyptian Sinai Peninsula mine site. After eight years of study using high-resolution pH๏τos and 3D scans provided by Harvard’s Semitic Museum, Bar-Ron says he has discovered two inscriptions reading “zot mi’Moshe” — Hebrew for “This is from Moses” — and “ne’um Moshe”, which means “A saying of Moses.”

If verified, these would be the oldest extra-biblical inscriptional references to Moses, a figure long documented in religious tradition but never confirmed by archaeology. The inscriptions are part of a group of over two dozen Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions first unearthed by Sir William Flinders Petrie early in the 20th century. These writings, which were likely created by Semitic-speaking laborers during the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III (c. 1800 BC), represent some of the earliest alphabetic texts known, even predating Phoenician.

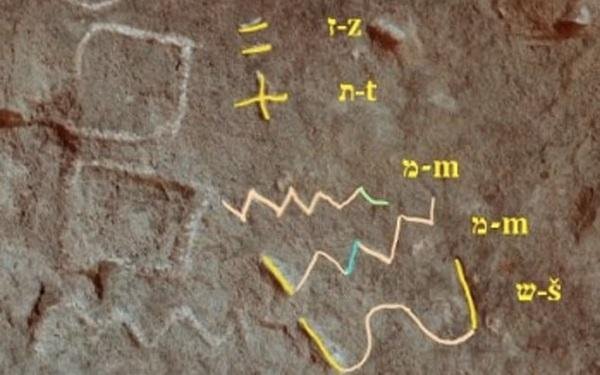

A controversial Proto-Sinaitic inscription from Serabit el-Khadim, believed by some to reference Moses. Credit: Michael S. Bar-Ron / Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

A controversial Proto-Sinaitic inscription from Serabit el-Khadim, believed by some to reference Moses. Credit: Michael S. Bar-Ron / Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz

Bar-Ron’s theory is not, however, without debate. In his proto-thesis (or early thesis), he suggests that these inscriptions are the voice of a single scribe who had knowledge of Egyptian hieroglyphs and used Proto-Sinaitic script to encode religious and personal messages. He believes the personal tone and poetic form of the scribe support a single authorship.

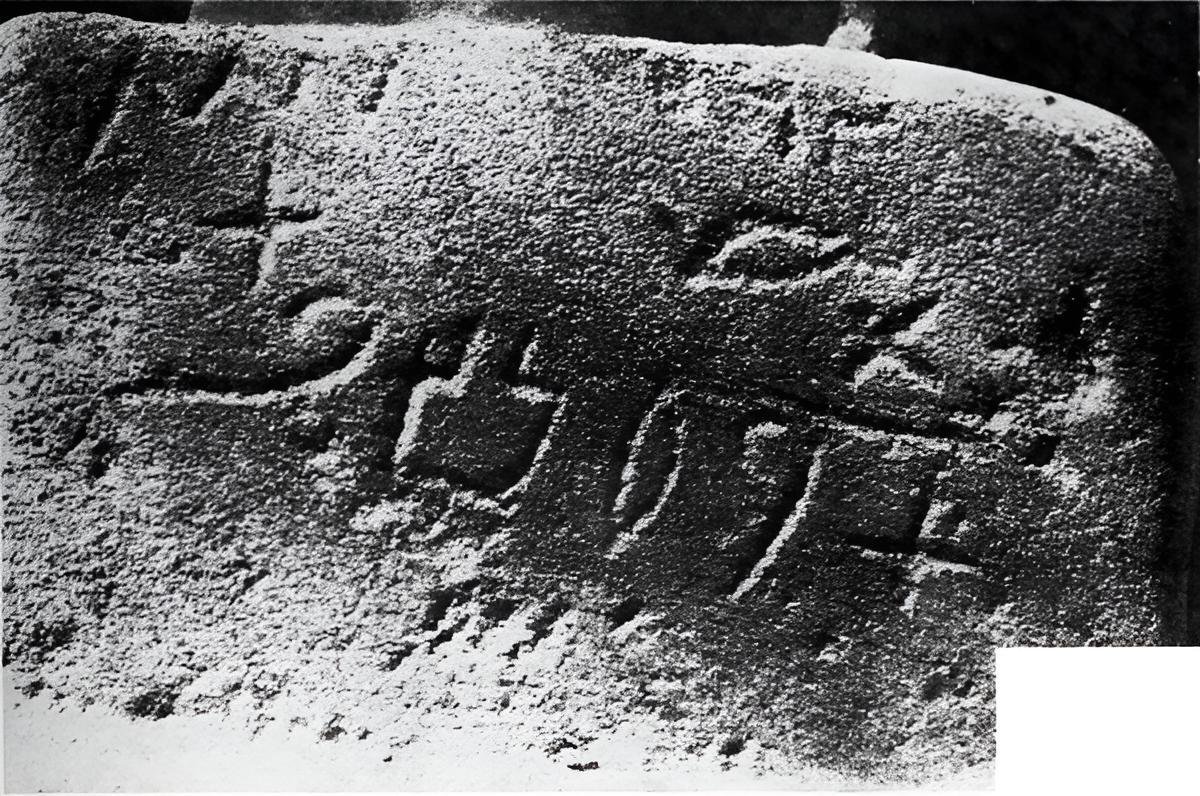

Specimen of the only certainly deciphered word in the Proto-Sinaitic script, b‘lt. circa 1500 BCE; PH๏τo c. 1916. Credit: Kwamikagami

Specimen of the only certainly deciphered word in the Proto-Sinaitic script, b‘lt. circa 1500 BCE; PH๏τo c. 1916. Credit: Kwamikagami

The inscriptions yield more than possible personal markings. Nearby inscriptions contain invocations to “El,” the archaic Hebrew deity, while others praise Baʿalat, the Semitic counterpart of the Egyptian goddess Hathor. Some of the inscriptions in honor of Baʿalat appear to have been scratched out by followers of El, pointing to a theological rift. A burnt temple dedicated to Baʿalat and inscriptions that mention “overseers,” “slavery,” and a call to depart—possibly to be interpreted as “ni’mosh” (“let us depart”)—give support to religious rebellion and mᴀss departure, recalling the biblical Exodus.

Archaeologists have also uncovered the Stele of Reniseneb and the seal of an Asiatic Egyptian official at the site, pointing to a strong Semitic presence. Bar-Ron even speculates a link to the biblical Joseph, making comparisons with figures like the Semitic vizier Ankhu, who served during the reign of Amenemhat III.

The ancient Serabit el-Khadim mining site in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, where the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions were uncovered. Credit: Roland Unger / CC BY-SA 3.0

The ancient Serabit el-Khadim mining site in Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula, where the Proto-Sinaitic inscriptions were uncovered. Credit: Roland Unger / CC BY-SA 3.0

Despite the hype, not everyone is convinced. Per The Daily Mail, Dr. Thomas Schneider, an Egyptologist at the University of British Columbia, dismissed the ᴀssertions, calling them “completely unproven and misleading,” and cautioning that “arbitrary identifications of letters can distort ancient history.” Proto-Sinaitic script is notoriously difficult to decode, and skeptics argue that subjective interpretations can easily lead to the wrong conclusions. But Bar-Ron’s academic advisor, Dr. Pieter van der Veen, supports his research.

Bar-Ron acknowledges that his research, which has not yet been peer-reviewed, is still in progress. He hopes that more research will either challenge or more conclusively prove his claims.

Whether or not the inscriptions refer to Moses, the finds at Serabit el-Khadim nonetheless revolutionize our understanding of ancient Semitic workers in Egypt and their evolving religious idenтιтies.