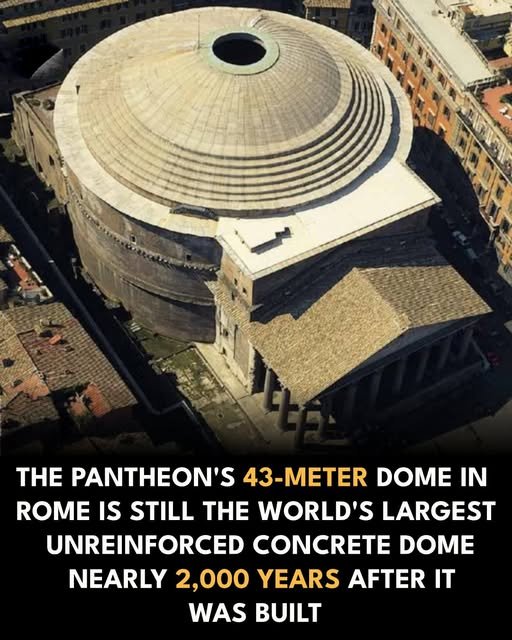

In the heart of modern Rome, among the chatter of tourists and the rumble of mopeds, there stands a building so ancient, so ambitious, and so hauntingly perfect that it defies time itself. It is the Pantheon, and atop its majestic rotunda rests a concrete miracle—the 43-meter-wide dome, still the largest unreinforced concrete dome in the world, nearly 2,000 years after it was first cast under the watchful eyes of Roman engineers.

But this is not just a marvel of measurements. The Pantheon is a cathedral to cosmic wonder, an echo chamber of empire, a place where architecture and theology embrace.

Built around 126 AD during the reign of Emperor Hadrian, the Pantheon as we know it was not the first structure to bear the name. Two earlier versions stood on the same site—both victims of fire and decay. But Hadrian’s version, with its vast dome and perfectly balanced proportions, would endure. He famously left the name of Marcus Agrippa, the builder of the original, on the front pediment: “M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT.” A humble gesture—or perhaps a political nod to Rome’s golden age.

What makes the dome so astonishing isn’t just its size. It’s how it was made—and what it was made for.

The ancient Romans had perfected the use of pozzolanic concrete, a volcanic ash mix that allowed them to build structures that would outlast empires. But to lift a dome 43 meters wide without steel reinforcement? To make it float above a temple without cracking, collapsing, or yielding? That was a feat of intuition, experimentation, and genius.

The dome is lighter at the top than at the base—an intentional gradient achieved by mixing the concrete with different materials. At the base, dense travertine provides weight and support. As the dome curves upward, lighter materials like tuff and pumice are used, reducing the load. The thickness also tapers—from over 6 meters at the base to just over 1 meter at the oculus.

And then there’s that oculus—the 9-meter-wide hole at the very top, open to the sky. It is the eye of the Pantheon, a cosmic spotlight, a bridge between human architecture and divine order. Through it pours sunlight, moonlight, rain, and the breath of the heavens. When you stand beneath it, your breath catches. Time slows. The eye watches you as much as you gaze through it.

This eye of the gods is not an ornament—it’s an engineering necessity. By reducing the load at the center, the oculus helped distribute weight outward, allowing the dome to stay aloft. But symbolically, it’s much more. Scholars argue it aligned with Roman ideas of the universe—the dome as the heavens, the oculus as the sun, the floor as the earth.

Step inside the Pantheon and the world changes. The proportions are exact: the height from floor to oculus equals the diameter of the dome. You are standing inside a perfect sphere, as if the gods had sliced a celestial orb in half and set it gently upon the earth. Light moves through the space like a sundial, tracing invisible paths across marble and gold.

It’s hard not to feel something spiritual.

Originally, the Pantheon was dedicated to all the gods—“pan” meaning “all,” and “theos” meaning “gods” in Greek. But which gods, exactly, is still a mystery. No statues remain from the original niches. Some say the seven planetary deities. Others whisper it was more philosophical—a monument to unity, to cosmos, to the convergence of Roman religious tolerance and imperial might.

In the 7th century, Pope Boniface IV converted the Pantheon into a Christian church, Santa Maria ad Martyres. This act of sanctification is what saved it from destruction during the Middle Ages, when so many pagan buildings were stripped for stone or forgotten. The Pantheon remained in continuous use for nearly two millennia—a sacred space to gods old and new.

Artists, emperors, and architects have all stood beneath this dome in awe. Michelangelo called it the work of angels, not men. Brunelleschi studied it before designing the dome of Florence’s cathedral. Thomas Jefferson borrowed its geometry for his vision of American democracy.

And yet, the Pantheon is not just a monument. It’s a living paradox.

It is light, and it is weight.

It is pagan, and it is Christian.

It is ancient, and it is eternal.

Even today, we don’t fully understand how the Romans achieved such longevity. The concrete, when tested, shows crystalline structures that resist time and corrosion. Modern engineers still study it, hoping to unlock its secrets. Perhaps the Pantheon has become more than a temple—it is now a textbook written in stone, whispering the lost language of Roman mastery.

Tourists gather here every day. They shuffle across the patterned marble floor. They stare up, open-mouthed, when the light hits the rotunda just right. Rain falls through the oculus, and drains hidden in the floor quietly whisk the water away. No signs. No fuss. Just elegance.

Some cry when they enter. Some fall silent. Some pray.

And for those who know history, there’s something else: a chill down the spine when they realize this structure, made by hand and hope, has outlived not just emperors and wars, but entire civilizations. The world burned, and still the dome remained.

Beneath the Pantheon, the ᴅᴇᴀᴅ lie in honored sleep—Raphael, the great painter, among them. He asked to be buried here, under what he called “a structure as perfect as the heavens.” It was his temple, too.

What is the Pantheon, really?

A temple?

A church?

An architectural puzzle?

A love letter to the divine?

It is all of these. And something more. It is proof that humans—when guided by faith, reason, and imagination—can reach across time. That the tools in our hands, if shaped by wonder, can build something that whispers even to the stars.

In a world that often forgets, the Pantheon remembers.

And so, it stands.

Stone and silence.

Dome and sky.

Waiting for us to look up—

And listen.