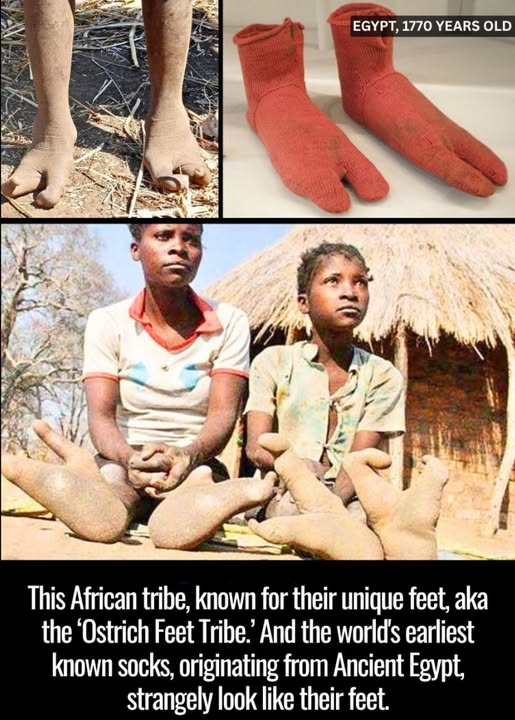

In a remote corner of southern Africa, deep within the parched earth and among the acacia trees, lives a small tribe whose physical appearance has stirred curiosity for generations. Known colloquially as the “Ostrich Feet Tribe,” the Vadoma people of Zimbabwe are bearers of a rare genetic condition that causes a striking difference in their anatomy—two large toes where most others have five, giving their feet an uncanny resemblance to those of an ostrich. For outsiders, their feet may seem like a medical anomaly, but for the Vadoma, they are part of their ancient idenтιтy, woven into folklore, survival, and resilience.

This condition, known as ectrodactyly, is a rare genetic mutation pᴀssed down through generations. In the Vadoma community, where marriage outside the tribe has historically been restricted, the gene pool remains relatively closed, making this condition more prevalent than elsewhere. The result? Feet that appear almost avian—spaced, strong, and surprisingly well adapted for navigating rough, thorny terrains barefoot. The Vadoma do not consider their feet a disability. Instead, they climb trees with agility, run across forests with ease, and live life in rhythm with the land—just as their ancestors did.

But what makes this tale even more fascinating is a seemingly unrelated archaeological find from an entirely different world: a pair of ancient socks discovered in Egypt, dated back nearly 1,800 years. Made from red wool and designed to be worn with sandals, these socks—now housed in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum—feature a peculiar design: a split between the big toe and the rest, much like a modern tabi sock or, as some now speculate, resembling the very feet of the Vadoma tribe. The resemblance is uncanny and stirs the imagination. Is it coincidence, parallel design, or some ancient connection lost in time?

The socks, crafted using nålbinding, a complex technique predating knitting, were not made for fashion but function. In the H๏τ Egyptian sun, sandals were practical, and split-toe socks allowed for warmth in the desert night while fitting seamlessly into open footwear. But why were they made this way centuries before the invention of tabi or toe socks in Asia? Was it purely utilitarian—or is there a deeper symbolism encoded in their design?

Here is where imagination and archaeology dance. Some anthropologists have speculated that the unique split-toe design might hint at something more than just comfort—it might reflect an ancient observation or cultural ideal. Could early Egyptians have encountered individuals or travelers with similarly shaped feet? Could this reflect a symbolic imitation of animals revered in their mythology—perhaps the ibis, falcon, or even the ostrich?

Interestingly, ostriches held deep significance in many African cultures, including those in Egypt. Their feathers were used in royal headdresses, and the ostrich itself often symbolized truth, balance, and the horizon between the earthly and the divine. To wear socks shaped like ostrich feet, then, might have been more than functional—it could have been spiritual, ritualistic, or even fashionable within a cultural context that we have yet to fully decipher.

The Vadoma, for their part, tell stories of being descendants of star people—echoes of celestial origin myths common among many Indigenous African tribes. They have long lived in isolation in Zimbabwe’s Zambezi Valley, resisting colonization and outside interference. Their lives revolve around the land—hunting, fishing, foraging—preserving a way of life that is as endangered as it is ancient. And yet, in this age of global fascination with anomalies and differences, their unique feet have placed them unintentionally at the center of speculation, wonder, and sometimes exploitation.

Modern science offers clarity, of course. Ectrodactyly is a well-documented genetic condition and appears sporadically across the world. But rarely is it seen on this scale, and rarely is it preserved in an unbroken cultural lineage like that of the Vadoma. And then, across the continent and through time, lie those 1,770-year-old Egyptian socks—a reminder that human creativity, adaptation, and expression often transcend continents and centuries.

What connects us all, ultimately, may not be uniformity but peculiarity. The Vadoma walk a path shaped by their ancestors. The anonymous Egyptian who sewed those socks lived in a society full of innovation and mysticism. Somewhere between them, across space and time, lies a story not of deformity or novelty—but of survival, culture, and the quiet poetry of human difference.

Perhaps the most moving part of this story is what it tells us about perception. What some see as oddity, others see as strength. Where one culture might design a garment to accommodate a shape, another builds a life around that shape. What if these moments of connection—between an African tribe and an Egyptian artifact—are not merely accidents of biology and craftsmanship, but reminders that our differences, no matter how outwardly strange, are threads in the same ancient human fabric?

So next time you see a sock—or your own foot—pause for a moment. In its design lies an echo of survival, of geography, of adaptation. And maybe, just maybe, an echo of the Vadoma child sitting proudly under the sun in Zimbabwe, and a forgotten Egyptian artisan threading red wool into the desert wind.