Long before the great stone towers of Babylon or the golden spires of Thebes, there was Çatalhöyük—an ancient city built not of kings and conquests, but of families, rooftops, and a quiet revolution in human society. Nestled in the Konya Plain of central Anatolia, this 9,000-year-old Neolithic settlement stood as one of the earliest known urban experiments. But in recent years, science has begun to whisper secrets from its dust, and they tell a story that overturns everything we thought we knew about ancient power and gender.

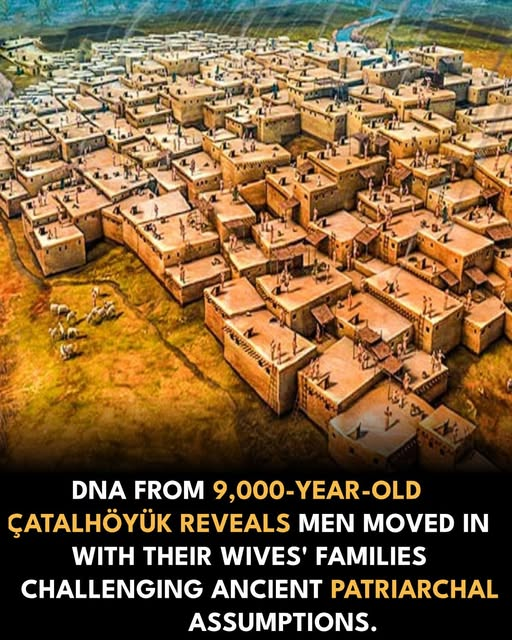

Çatalhöyük was not just old—it was extraordinary. Founded around 7100 BCE and thriving for over a millennium, the settlement was home to as many as 8,000 people at its peak. Its architecture was like nothing else in the ancient world. There were no streets. Instead, people entered their mud-brick homes through holes in the roof, walking across the city as if on a living labyrinth of ceilings. Each house was a mirror of another—equal in form and function—suggesting a startling lack of hierarchy. No palaces, no temples, no signs of centralized authority. But the most profound discovery lay not in its walls, but in its bones.

Recent DNA analysis from buried remains in Çatalhöyük revealed a pattern that shocked archaeologists. While women tended to be buried near their maternal relatives, men were not. This indicated something rare: patrilocality was not the norm. Instead, men married into and lived with their wives’ families. In other words, Çatalhöyük was likely a matrilocal society—one where women held the ancestral hearth, and men joined them as guests who, over time, became kin.

This quiet subversion of patriarchal ᴀssumption changes everything. For generations, scholars ᴀssumed early civilizations were dominated by male lineage and control. But Çatalhöyük suggests that before the rise of kings and warriors, there were mothers, daughters, and grandmothers holding the center of communal life. The homes themselves, plastered over with layers of white and ochre, preserved memories of their occupants—many of whom were buried beneath the floors, returning to the very earth that sustained them. Domestic space wasn’t just shelter; it was sacred lineage.

Inside these homes, the walls spoke with pigment. Bulls’ horns, painted goddesses, vultures in flight, and geometric symbols formed an early visual language, possibly religious, possibly mythological. But among them, the repeated presence of feminine motifs has led some to speculate that Çatalhöyük was not just matrilocal—but also matrifocal, centered around the spiritual and social power of women. Whether or not goddesses ruled their cosmology, it is clear that women held something profound: continuity.

This is not to say Çatalhöyük was utopia. Its people lived hard lives. Skeletons show signs of injury and disease. The тιԍнтly packed homes may have fostered a sense of equality but also a fragility—when one wall crumbled, many did. Yet in their proximity, in their repeated rituals of death and rebirth within the same space, they built something remarkable: a society not defined by domination, but by connection. Not by towers of power, but by rooms of memory.

Today, as the modern world wrestles with old and new inequalities, the people of Çatalhöyük offer a lesson from deep time. Societies need not be patriarchal to endure. Strength can flow from the hearth, from mothers pᴀssing stories and land to daughters, from men stepping into homes not to conquer, but to belong.

Their bones have spoken. Their walls still stand. Their rooftops stretch into the horizon of time like a quiet hymn to a different way of being.

And so, we must ask ourselves: What other truths lie buried beneath our ᴀssumptions, waiting to rewrite the story of us all?