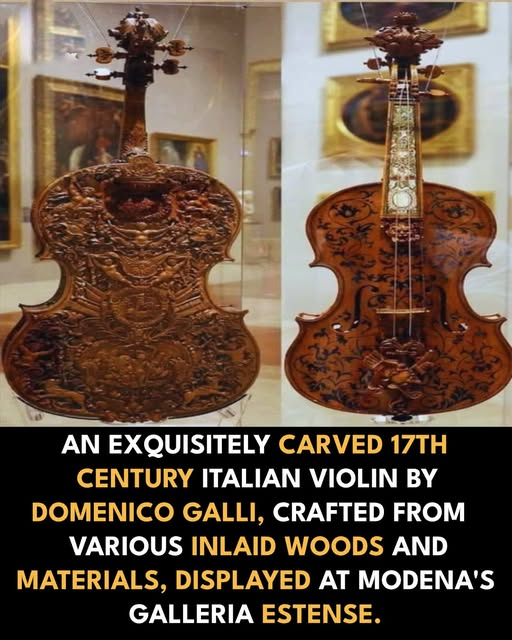

In the heart of Modena, Italy, beneath the gilded arches of Galleria Estense, rests a violin that has not been played in centuries—but sings louder than any symphony. Crafted in the late 17th century by the skilled hand of Domenico Galli, this extraordinary violin defies its purpose not through defiance, but through devotion. It was never simply meant to be heard. It was meant to be seen, admired, studied—a visual hymn to craftsmanship, music, and the eternal dialogue between artist and instrument.

Born into the golden age of Italian luthiery, Domenico Galli was not merely a violin maker—he was a sculptor, an artisan, a visionary who dared to let the violin transcend its sonic duty. This particular instrument, likely completed around the 1680s, was carved not just with tools but with reverence. Every inch is a story etched in wood: a tapestry of vines, cherubs, mythical beasts, and floral motifs, all swirling across the maple and spruce body like notes on a celestial staff. It is a violin that appears to breathe, to pulse with the same elegance as the music it was designed to produce.

Constructed using inlaid woods from across Europe—ebony, rosewood, walnut, and more—the violin’s visual complexity mirrors the cultural richness of Baroque Italy. The back plate alone is a relief sculpture worthy of standing beside the finest marbles of Florence or Rome. With every carved curve, Galli paid tribute not just to luthier tradition, but to the deeper philosophy of the time: that beauty was divine, and that craftsmanship was its earthly echo.

Though Galli’s name may not ring as loudly as Stradivari’s or Guarneri’s, this violin remains one of the finest surviving examples of Baroque decorative art in the form of a musical instrument. It was likely commissioned by an aristocrat, perhaps one who saw music not merely as an auditory experience, but as a symbol of wealth, power, and cultivated taste. The instrument was never meant for the stage—it was created for chambers lit by candlelight, where nobles whispered over string quartets and admired the ornamentation as much as the harmonies.

Yet what elevates this violin beyond mere beauty is the paradox it represents. It is a silent instrument, preserved in stillness. No rosin touches its strings. No bow disturbs the hush that surrounds it. It has become a sculpture of music, the very embodiment of sound turned to silence. And in that silence, one begins to wonder: What songs did it once dream of playing? What fingers almost touched it in performance but stopped short in awe?

To stand before this violin is to feel a pang of longing—for a melody never heard, for a craftsman’s hands stilled by time, for an era when creation was as sacred as sound. It whispers to us, not in pitch, but in form. It reminds us that art is not bound to one sense alone. And more importantly, it asks a quiet question that has echoed through every generation of creators:

Is the purpose of art to be used, or simply to exist as a testament to human wonder?

In that question lies the eternal song of Domenico Galli’s violin—haunting, wordless, and forever beautiful.