The sun rises slowly over the Sacred Valley of the Incas, warming the Andean peaks with a golden hue that has kissed these same stones for over half a millennium. In the quiet village of Ollantaytambo, the ancient stonework begins to glow with life—lines and seams between mᴀssive slabs revealing something almost imperceptible at first glance: tiny insets in the shape of a ʙuттerfly or an hourglᴀss, carved with divine precision.

These are not mere decorations, nor symbols. They are solutions—answers from a civilization that never wrote a formal script but told their story in rock. Known today as the Inca ʙuттerfly clamps, these features hold together mᴀssive stones that once formed part of roads, terraces, and temples across the highlands of Peru. But more than tools of construction, they are silent witnesses to a world that understood patience, time, and stone better than most.

A City Built on Stone and Sky

Ollantaytambo was more than a fortress. It was a temple, a royal estate, a center of ceremony and science. Nestled between steep mountains and bisected by the Urubamba River, it stood like a hinge between heaven and earth—its stones heavy with purpose, its pathways whispering stories to the wind.

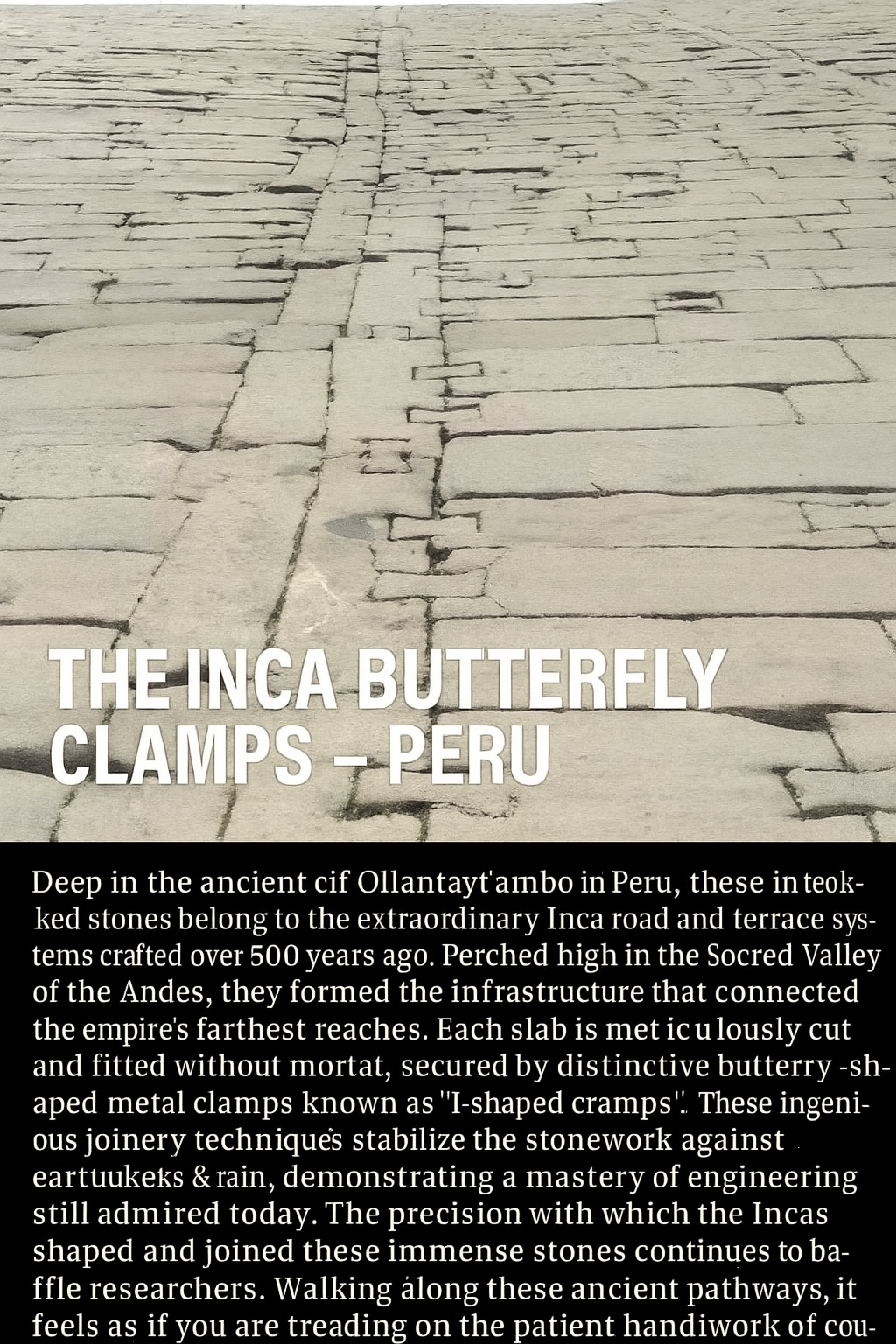

To the untrained eye, the road might seem like a simple path, aged and cracked by centuries. But look closer—really look—and you begin to see the genius beneath your feet. The stones are mᴀssive, some weighing more than a modern truck, yet they fit together without a trace of mortar. Between many of them, thin ʙuттerfly-shaped recesses have been carved, and into these, ancient Inca engineers fitted metal clamps—likely of bronze or an alloy that resisted corrosion.

These clamps acted as keys between the stones, locking them together against earthquakes, erosion, and time. While empires elsewhere relied on brick, plaster, or cement, the Inca trusted geometry and pressure. Their architecture didn’t resist nature—it danced with it.

The Forgotten Equation

There is no written record explaining exactly how the Incas cut these stones with such accuracy or how they transported them across mountainous terrain without the wheel. What we know comes from Spanish chroniclers, oral history, and the stones themselves.

Archaeologists first noticed these ʙuттerfly clamps at sites like Ollantaytambo and Cusco. Some clamps were made of copper alloys, while others left only the cavities behind—ghosts of ancient engineering. The method suggested a deep understanding of stress distribution, load balance, and interlocking systems. The ʙuттerfly, with its widened ends and narrow middle, distributes force evenly—making it ideal for stabilizing large slabs of stone.

But the most curious part? The clamps weren’t always visible. In many cases, they were embedded deep within the stones, covered by precisely fitted slabs. They weren’t meant to impress. They were meant to work.

The Hands Behind the Stone

Imagine, for a moment, the craftsmen who carved these roads. They did not use power tools or lasers, yet their tolerances were so тιԍнт that not even a blade of grᴀss could slide between two stones. Their tools were likely made of harder stone, water, sand, and intense patience. Each cut, each groove, was an act of devotion—perhaps even a prayer.

One can almost see them now: hunched over, sunlight bouncing off bronze, pausing not from exhaustion but from awe—because they weren’t just building a road; they were building continuity. Their work was not for kings alone, but for the people, the land, the gods.

They understood something many modern builders forget: permanence isn’t about resisting change—it’s about adapting with it. When an earthquake trembled through the Andes, Inca walls would sway but not fall. Their rounded corners, inward-leaning angles, and clamp-locked stones gave the structures flexibility and life.

Echoes in Metal and Dust

Today, many of the ʙuттerfly clamps have vanished—looted for metal, lost to erosion, or corroded into invisibility. What remains are the cavities: precise and stubborn, refusing to be erased. These voids speak louder than many monuments. They remind us that knowledge can endure without ink, without books, without fame. It can endure in craft, in gesture, in silence.

Modern engineers marvel at the clamps. How did the Inca heat the metal and pour it into place without cracking the surrounding stone? Some suggest they poured molten metal into the grooves onsite; others believe the clamps were forged elsewhere and hammered in. Either way, it required a harmony of metallurgy and stonemasonry that speaks of a civilization far more advanced than often credited.

And all of this—this elegance and exactness—was done not for glory, but for use. These clamps were rarely seen. They were buried in foundations, hidden beneath roads, quiet in their labor. They weren’t meant to be admired. They were meant to hold.

A Walk Through Time

To walk upon these roads is to walk with ghosts. Each step reverberates with centuries of footsteps—from Inca messengers running with quipu messages to Spanish conquistadors, to modern travelers marveling at the resilience beneath their feet. The stones are warm underfoot, humming with history.

You wonder: what stories have pᴀssed through here? What rituals? What conversations? Perhaps lovers walked here in the moonlight. Perhaps a priest once knelt to pray where now tourists pause for selfies. Perhaps a child once traced the edge of a clamp cavity, wondering what lay beneath.

These clamps connect more than stone—they connect people. Across time, across culture, across conquest and rediscovery, they hold together a legacy that refuses to crumble.

The Soul of the Andes

Ollantaytambo is only one chapter in the Inca story, but it is one of the most enduring. It was here that resistance flared against the Spanish, where Manco Inca repelled conquistadors with guerrilla brilliance. It was here that the river and the mountain met, and the Inca shaped both into an axis of civilization.

The ʙuттerfly clamp, small as it seems, is a symbol of that ethos. It is the Inca way distilled—quiet mastery, humble brilliance, the merging of nature and design. Like the ʙuттerfly itself, it suggests transformation, fragility turned strength.

And perhaps that is why the clamps fascinate us still. They remind us that genius often hides in the margins. That the most enduring legacies are not carved in gold, but in stone joined by unseen hands.

A Question Left in Stone

As you stand upon the ancient road, the sun now sinking behind the Andean ridges, you feel the wind shift. It moves through the stones, through the clamps, through you. You feel, unmistakably, that you are not alone.

So you ask yourself—not aloud, but inwardly: What will we leave behind that holds as firmly, as wisely, as this?