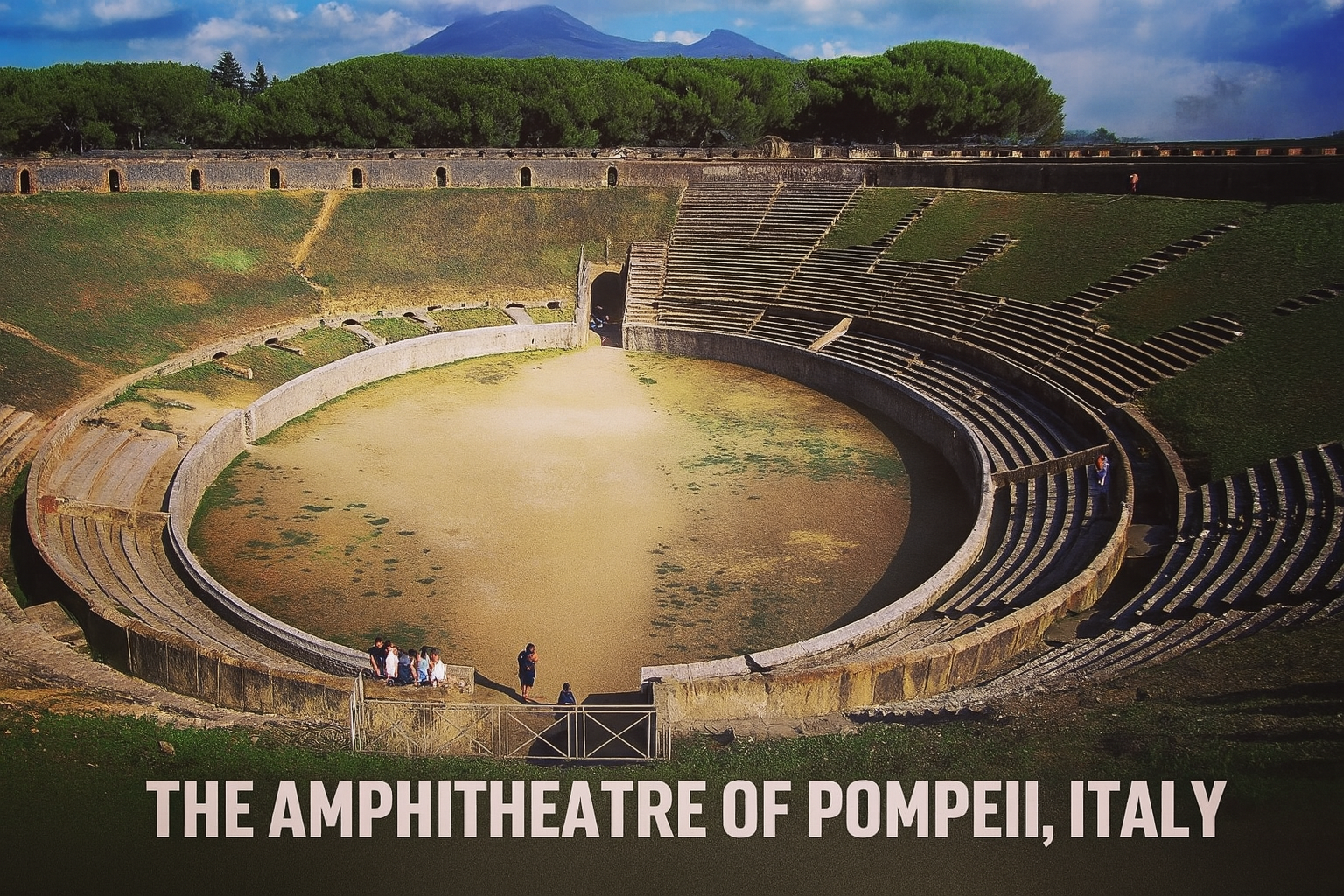

There is a stillness in Pompeii that defies time. The city sleeps beneath layers of volcanic ash, and yet it breathes through stone archways and cobbled streets. At the edge of this silent city stands an ancient amphitheater, perfectly oval, carved into the Earth like a wound that never healed. Here, where the ghosts of gladiators once paced beneath the roar of a thousand voices, silence now reigns.

Built around 80 BCE, the Amphitheater of Pompeii is the oldest surviving Roman amphitheater in the world. Before the grandeur of the Colosseum in Rome, before the emperors built spectacles for their own glorification, there was this place—simple, elegant, brutal. Its creators were not just architects but visionaries, for they carved from the land a place where power, fear, and courage would dance in the dust of human drama.

The arena was capable of holding 20,000 spectators—an astonishing number when you consider that Pompeii itself may have had only around 11,000 residents. They came from nearby towns, drawn not just by the violence, but by the ritual. It was here that slaves became warriors, that emperors tested public favor, that blood was spilled to entertain the gods and the crowd alike. And unlike later amphitheaters, this one lacked the underground chambers or hypogeum. Everything happened in the open, raw and unfiltered.

In the early morning, the arena is bathed in soft Mediterranean light. The sun creeps across the broken stone seats where once vendors hawked wine and olives. Children clutched their fathers’ tunics, wide-eyed, as the gladiators marched into the ring. The scent of sweat, iron, and anticipation would have clung to the air like smoke.

If you stand in the center of the arena now, the silence is deafening. Grᴀss grows where blood once soaked the earth. Time has bleached the stone, but it hasn’t erased the emotion—the fear, the pride, the fury. It’s as if the souls of those who lived and died here are etched into the walls themselves. Some say they can still hear the echo of cheers, or the clash of sword against shield, carried on the breeze from Vesuvius.

Ah yes—Vesuvius. The sleeping giant that woke on an August afternoon in 79 CE and ended everything.

The eruption was cataclysmic. Ash, pumice, and gas enveloped Pompeii in hours. Roofs collapsed, streets were buried, people froze mid-motion. The amphitheater, like the rest of the city, vanished under a sea of volcanic debris. But it was not destroyed. It was preserved, eerily intact, like a stage waiting for its actors to return. For nearly 1,700 years, the arena lay hidden. When it was finally rediscovered, archaeologists marveled at how the walls still stood, the steps still curved with perfect Roman precision.

But it wasn’t just the structure they found. It was the humanity.

In a city frozen in time, every detail is a glimpse into the ancient soul. Graffiti still adorns the amphitheater’s inner walls—some of it crude, some poetic. Messages like “Celadus the Thracian makes the girls sigh” remind us that these weren’t just faceless warriors; they were celebrities, heartthrobs, and legends in their own right. The games were theater, and the amphitheater was the grandest stage in Campania.

The arena also bore witness to darker moments. In 59 CE, a bloody riot broke out between the Pompeians and neighboring Nucerians during a gladiatorial game. It was so violent that Emperor Nero banned such games in the city for ten years. Even in a place designed for bloodsport, the violence exceeded what was acceptable. It was a reminder that Roman arenas were not just places of entertainment, but volatile cauldrons of civic emotion.

As you walk the circular steps now, it’s easy to imagine the hierarchy embedded in every row. The wealthy and powerful near the front, the poor and enslaved at the top. The games were free, but the view you received was a reminder of who you were in the pecking order. Even in death, Rome was structured.

Yet despite the blood and the class divide, there’s something deeply human about this place. It’s a monument not just to cruelty, but to resilience. To the primal need for story, conflict, and spectacle. The amphitheater was where society came together—not always kindly, not always nobly—but undeniably. It was the beating heart of Pompeii, and perhaps its most honest mirror.

Today, the trees have grown tall behind the arena. Their green canopy sways gently in the breeze, a stark contrast to the barren earth below. In the distance, Mount Vesuvius looms—serene, yet ominous. A constant reminder of how quickly civilization can turn to silence.

And yet, people return. Tourists from every corner of the globe step into this arena not to fight, but to feel. To imagine. To remember. The amphitheater still performs, in a sense—its stories now told in whispers and footfalls, not sword and scream.

Pompeii teaches us something profound: that even in ruin, beauty survives. That memory is stronger than stone. And that sometimes, the most powerful voices are the ones no longer speaking.

If you ever find yourself walking through its arched entry, pause at the threshold. Close your eyes. Listen. You may hear them still—the cheer of the crowd, the crack of a whip, the final breath of a hero beneath the southern sun.

And ask yourself: what would you fight for, if the world were watching?