On a crisp February morning in 2022, the narrow alleys of Stari Grad, Croatia—the oldest town on Hvar Island and one of the oldest in Europe—were alive with the hum of construction. What began as a routine utility project along the timeworn limestone streets quickly turned into an archaeological awakening. As workers lifted flagstones to access the pipes below, a familiar pattern emerged—not in modern infrastructure, but in tesserae: tiny, hand-cut stones arranged in a mosaic untouched by sunlight for generations. What they had found, again, was history.

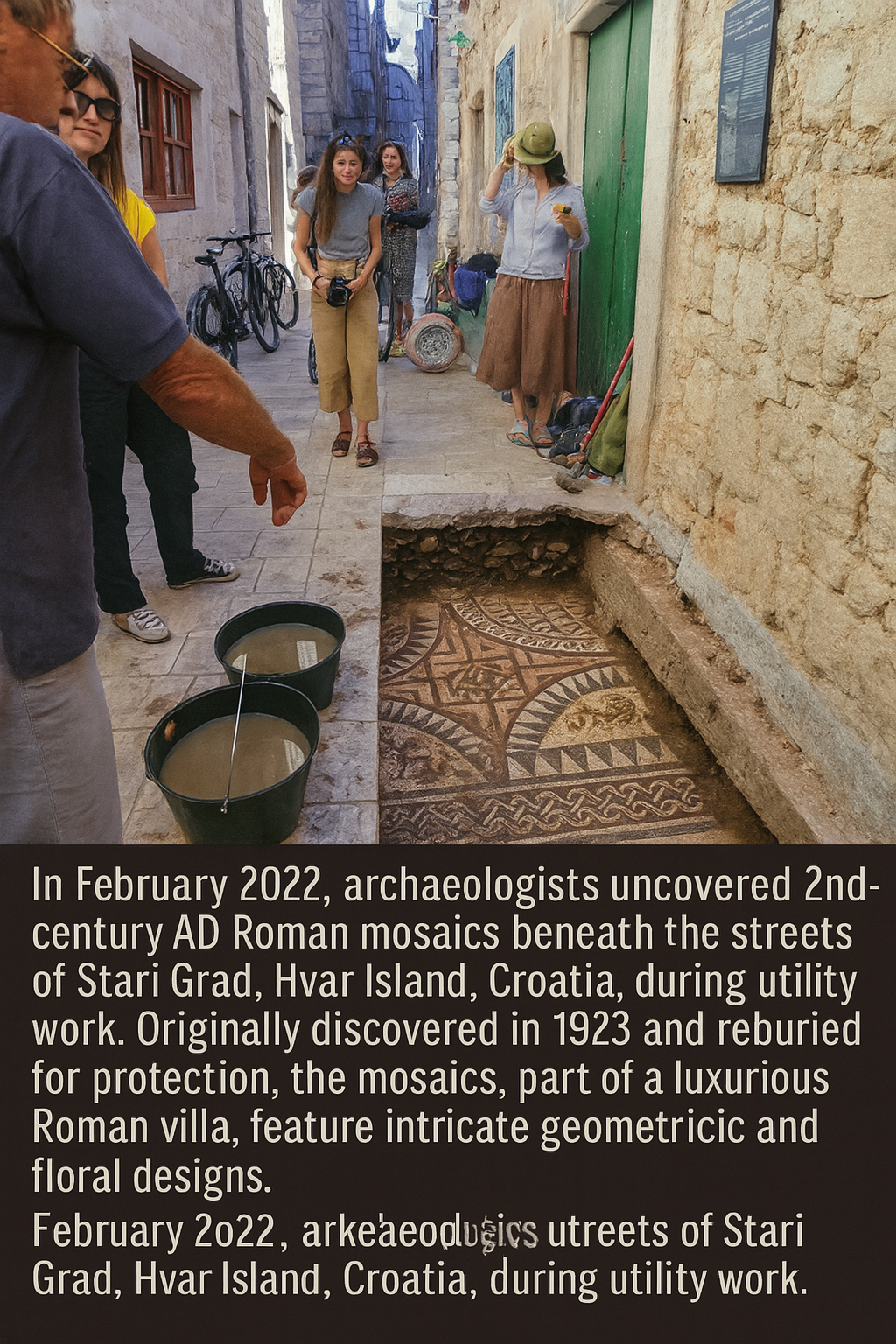

Word spread quickly, as it always does in small towns where past and present share every corner. Within hours, archaeologists arrived. A team, led by local preservationists, gently removed the remaining layers of dirt, revealing the bold reds, soft ivories, and faded blacks of an ancient Roman mosaic floor. These were no ordinary patterns. They were the meticulously laid motifs of a 2nd-century Roman villa: intertwining florals, braided borders, and geometric spirals that danced with the precision and elegance of a forgotten empire.

But this was not the first time the mosaics had seen the light.

A century earlier, in 1923, these very tiles had been discovered during earlier urban work. Recognizing their value but lacking the resources for conservation, archaeologists then made a practical choice—they reburied the mosaics, sealing them beneath the cobblestones in hopes that future generations would do better. For nearly 100 years, the villa floor lay sleeping beneath the feet of locals and tourists alike. Life moved above it: bicycles rattled over it, children played along the walls, the sea breeze swept dust into corners, and no one remembered the silent grandeur just below.

Stari Grad—known as Faros when it was founded by the Greeks in 384 BCE—is a town that wears its age with grace. Its stone houses lean slightly, as though in quiet conversation with the past. Here, history isn’t behind glᴀss but layered into daily life. The Roman presence, though distant in time, never fully vanished. The discovery of the mosaic—its artistry, its precision—was a tangible reminder that the past isn’t lost, only waiting to be seen.

As the excavation deepened, so did the sense of awe. The mosaic, scholars confirmed, was part of a luxurious Roman domus, likely belonging to a wealthy merchant or retired officer who chose the fertile fields and gentle bays of Hvar as his final home. The villa would have once opened toward the sea, its colonnades casting cool shadows across frescoed walls. Perhaps olive oil or wine had flowed from its storerooms. Perhaps the owner walked this very mosaic floor while discussing trade routes and emperors. Each stone, each curve, was a whisper from a life long vanished.

Tourists wandered by the site, drawn in by curiosity and surprise. Children leaned over the edge, wide-eyed, while older locals recalled hearing about the “mosaic that disappeared” from their grandparents. For the archaeologists, it was a moment of communion—not just with the people around them, but with their predecessors from 1923. They were finishing a conversation begun a century ago.

The most striking part of the mosaic was not its survival, but its artistry. The floral patterns—stylized vines and palmettes—were more than decoration. They spoke of Roman ideals: harmony, permanence, the civilizing power of beauty. The geometric forms reflected a worldview governed by proportion and order. In a time when much of the world was in chaos, these symbols conveyed a sense of mastery over both nature and time.

Yet this mastery was fleeting. By the 4th or 5th century, the villa was likely abandoned. Rome’s grip on the Adriatic loosened, and new powers, new religions, and new languages washed over the islands. The floor, once polished daily, gathered dust. Walls crumbled. Roofs collapsed. Eventually, the Earth swallowed the villa whole—until a shovel blade in 1923 disturbed its sleep. And again, in 2022, the silence was broken.

One archaeologist described the moment of revelation as “watching the floor blink open its eyes.” Another said she felt as if she were walking into someone’s memory. But it wasn’t just professionals who were moved. A young pH๏τographer, visiting Stari Grad from Zagreb, sat by the dig every afternoon, documenting not only the mosaic but the changing expressions of the townspeople who came to see it. “It feels alive,” she said. “Like it’s remembering us too.”

There’s something profoundly intimate about standing inches from a hand-laid floor that has outlived empires. You can almost feel the footsteps that once pᴀssed there. The laughter. The grief. The daily routines of a family whose names are long lost, but whose desire for beauty remains frozen in stone.

The challenge now was preservation. Archaeologists and conservators debated what to do. To leave it exposed was risky; the sun, tourists, and the salt air could damage the ancient stones. To re-bury it again felt tragic—like tucking away a miracle. Ultimately, a compromise emerged: document and preserve as much as possible now, and design a long-term plan that would allow future visitors to experience the site safely and meaningfully. Technology offered some hope: pH๏τogrammetry, 3D scanning, and augmented reality tools would make it possible to explore the mosaic virtually, even if it were covered once more.

In a town like Stari Grad, where every alley echoes with stories, this discovery felt less like an interruption and more like a reunion. It reminded residents that they are part of a longer arc—a chapter in a book that began with Greek sailors, Roman engineers, Slavic settlers, Venetian merchants, and now Croatian dreamers.

The mosaic isn’t just a floor. It’s a conversation starter. It bridges the pragmatic present with the poetic past. And it asks quiet questions of all who look upon it: What will our floors say about us in 2000 years? What patterns do we leave behind? What beauty, what care, what silence?

As the sun set on Stari Grad and the archaeologists gently re-covered the exposed corner of the Roman villa, a small boy stood with his mother nearby. He pointed to the ground and asked, “Will they find our house like this one day?”

His mother smiled, then said what all archaeologists secretly hope is true: “Maybe. If we take care of it.”

And in that moment, the mosaic continued to live—not just as artifact, but as legacy.