In the mid-19th century, when the sun cast long golden fingers over the dusty hills of Attica, and Athens was still a city reborn from centuries of foreign dominion, a traveler might have stood at this very spot and gazed in stunned silence. Before him rose a monument not only to architecture or empire—but to memory itself. The Acropolis of Athens, ancient citadel of gods and philosophers, loomed like a forgotten crown, worn yet luminous, etched into the heavens.

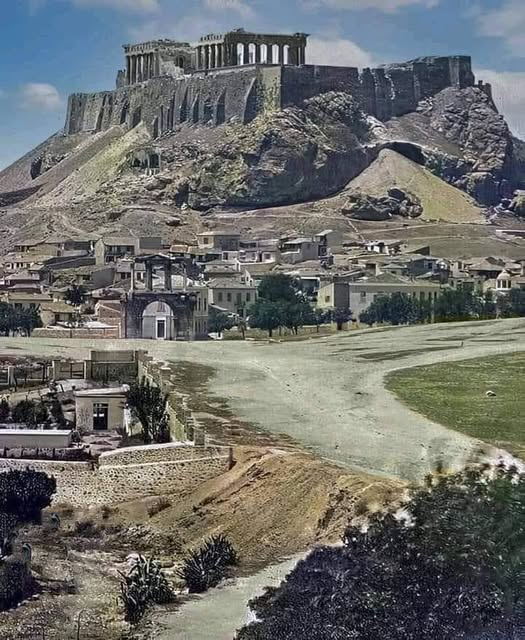

This image, taken around 1865, is no ordinary pH๏τograph—it is a doorway into a city caught between two worlds: the quiet rural rhythms of post-Ottoman Greece and the mythic heartbeat of ancient glory. The Parthenon, standing stoic atop its sacred rock, dominates the skyline like an oracle carved in stone. Yet below, something unexpected unfolds. Not tourist crowds or sweeping boulevards, but a gentle sprawl of modest homes, tangled gardens, wandering goats, and voices speaking in hushed tones of transition and hope.

Echoes in Stone: A Citadel’s Long Memory

The Acropolis—whose very name means “high city”—has stood since time almost untold. Though fortified since the Bronze Age, it was during the 5th century BCE, under the ambitious statesmanship of Pericles, that the marble masterpiece we now revere came into being. The Parthenon, temple of Athena Parthenos, goddess of wisdom and war, was raised not just in devotion, but in triumph, as Athens basked in its golden age.

Its architects, Iktinos and Kallikrates, and the sculptor Phidias, shaped not only stone but time. Each column of the Parthenon leans inward, each line bows subtly against optical illusion, every carved metope tells a tale: centaurs battling Lapiths, gods surveying mortals, the harmony of a civilization forging order from chaos.

And yet, centuries pᴀssed. Empires shifted. The Parthenon became a church, then a mosque. In 1687, during a Venetian bombardment of the Ottoman-held Acropolis, a shell struck the powder magazine stored inside the Parthenon—blasting apart centuries of harmony in an instant. Marble fell like snow. Statues shattered into ghostly fragments.

Still, the Acropolis endured.

Beneath the Rock: The Quiet City Awakens

Look again at the pH๏τograph. This is not the bustling Athens of today, but a modest village-like capital emerging from the long shadow of empire. Greece had won its independence from the Ottomans only a few decades earlier, and Athens, chosen as the new capital in 1834, was still shaking off centuries of foreign rule. In the foreground, dusty streets meander like ancient riverbeds. Olive trees lean curiously toward the sun. Children, dressed in vests and wool, may have been running just out of frame.

The air would have carried a mingling of scents—goat milk, warm bread, jasmine vines curling up wooden porches. And always, above it all, the Acropolis watched.

At the base of the hill, near the old Roman Agora, stands the Gate of Athena Archegetis, its columns still upright, as though resisting erasure by sheer will. Nearby, the ancient Library of Hadrian rests, a ruin touched by more than time: a Roman emperor’s dream of enlightenment, now visited only by goats and scholars.

Even in the pH๏τograph’s silence, you can feel the Acropolis whispering to those below.

An Archaeologist’s Dream, a Nation’s Heart

To the early archaeologists and historians of the 19th century, this landscape was more than romantic—it was sacred. Greek idenтιтy, newly rekindled after centuries of Ottoman rule, found its rallying cry not only in the present but in the mythic past. The Acropolis became more than a monument. It was a symbol of continuity, of lost glory reborn.

Excavations began. Scholars from across Europe came to unearth fragments of the past—pottery, foundations, statues half-buried in soil. But their efforts, too, were shaped by time and tragedy. Much of the Parthenon’s finest sculpture had already been taken—famously removed by Lord Elgin in the early 1800s and shipped to Britain, where it remains to this day in the British Museum. To Greeks, these were not just art—they were soul.

So, as this pH๏τograph was taken, the battle over memory was just beginning. Restoration projects would soon begin. Some stones would be returned to their place, others lost forever. But the conversation—the pain and pride of idenтιтy—was now woven into the very marble.

The People Below: Ordinary Lives in Sacred Shadows

We often forget, when speaking of monuments and kings, that history is lived in kitchens and courtyards. Who were the people who lived beneath the Acropolis in this moment? Fishermen and priests, schoolteachers and shepherds, widows who had buried sons in forgotten wars. Life was not easy. The new Greek state was fragile, its politics volatile, its economy strained. Yet there was joy too—in weddings held in small chapels, in laughter echoing against whitewashed stone, in the steady resilience of a people who had waited generations to reclaim their voice.

Perhaps a young boy, climbing the hill barefooted, dreamed not of becoming a philosopher or warrior—but simply of watching the sunrise from the Parthenon’s steps, where gods once stood.

A Monument to What Endures

Time is the great equalizer. Kingdoms fall. Beliefs shift. Stones crack. But what remains is not just what was built—but what is remembered.

This pH๏τograph is a portal, not only to a place but to a feeling—a delicate moment when the ancient world touched the modern one, when the weight of the past pressed gently upon the present, and Athens stood not only as a city, but as a story.

Today, the Acropolis sees millions of visitors a year. Its slopes are carefully guarded, its monuments heavily restored, its streets filled with voices from every nation. But look again at this image, and you will see a different kind of magic—not one of grandeur, but of intimacy. A city still dreaming, a people still healing, a monument still watching.

And you might ask yourself: What will we leave behind, when our stones have fallen silent?