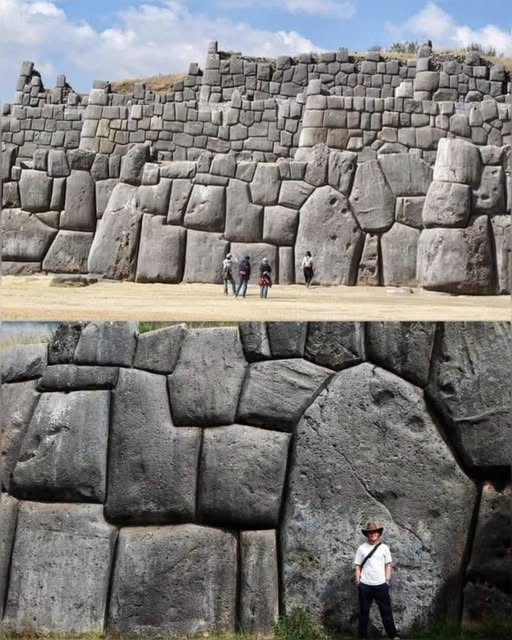

High in the Andes, where the wind is crisp and the clouds glide like white spirits over rugged peaks, there is a wall that defies belief. Not merely because of its scale, or the silent authority it radiates—but because it exists at all. Sacsayhuamán, the fortress above Cusco, is a riddle carved in stone, a monolith of mystery. And for those who walk beside it, like the man in the hat standing dwarfed by a single block in the pH๏τo, the experience is not merely archaeological—it is spiritual.

This is where Marco stood one sunlit afternoon, breathless not just from the alтιтude, but from awe. He had seen pH๏τos before. Documentaries. Journal articles. But nothing prepared him for the sensation of standing before the wall in person. It rose in tiered layers, cyclopean in nature, each stone uniquely shaped, like pieces of a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle forged not in a workshop, but by тιтanic hands and primeval forces.

No mortar. No binding agent. Just precision—perfect, polygonal precision.

Sacsayhuamán was built by the Inca, or so the consensus claims. But even that is debated. The Spanish conquistadors who reached Cusco in the 16th century were dumbfounded by what they saw. The sheer size of the stones—some weighing more than 100 tons—seemed beyond the scope of human capability, especially in a civilization that lacked iron tools, wheels, or draft animals. The chronicler Garcilaso de la Vega wrote of the fortress as a “work that no human could replicate,” marveling at how the blocks fit so тιԍнтly that not even a blade of grᴀss could slip between them.

Marco touched one of the stones. It was warm from the sun, cold underneath—ancient and alive. You could run your hand along the edge and never feel a seam. He imagined the craftsmen who had shaped and moved these boulders, the whispered instructions pᴀssed through generations, the ritual offerings to the mountain gods before each stone was set.

Some theories say the stones were dragged up inclines, rolled on logs, or carved with stone tools using sheer patience and skill. Others—more fringe but no less pᴀssionate—speak of lost knowledge, of sound manipulation, or even forgotten civilizations predating the Inca. In the lower levels of the wall, the blocks are largest—monsters of granite curved and notched like melted wax. The higher up you go, the stones get smaller, more angular. It’s as if the technology regressed with time.

The site’s name, Sacsayhuamán, translates roughly to “satisfied falcon” in Quechua. Some believe the structure mimics the head of a giant condor or puma, sacred animals in Andean cosmology. Others see the teeth of a god. The zig-zagging walls—three tiers deep—were not only defensive but symbolic, part of a grand urban plan that aligned the spiritual with the astronomical. Cusco itself, when viewed from above, was designed in the shape of a puma, with Sacsayhuamán as its head.

But Marco wasn’t thinking about pumas. He was thinking about people.

How many hands had cut these stones? How many lives were spent moving them, fitting them, honoring them? He could almost hear the chants of the workers, the scrape of stone on stone, the crack of ancient hammers, the hush of wind across the plateau. He tried to imagine the day the final stone slid into place. Was there cheering? Silence? A priest raising his arms to the sun?

Then came the Spaniards. The fortress was partially dismantled after the conquest. Many of the stones—especially the smaller ones—were taken to build colonial Cusco. But the largest remained, too heavy to move, too stubborn to be broken. It was as if the mountain refused to release them, as if these stones had chosen to stay.

Standing in front of one particularly mᴀssive block—twice his height and wider than a van—Marco felt dwarfed, not just physically but cosmically. This wasn’t just a wall. It was a threshold. Between time and eternity. Between what we know and what we long to understand.

Tourists milled around, snapping pH๏τos, laughing, posing. Children ran along the dusty path below. But Marco stayed still. He wanted to remember this moment not with pixels, but with breath. With skin. With memory.

As the sun began to descend behind the hills, the stones took on a golden hue, glowing softly like slumbering gods. Shadows stretched across the joints, highlighting the interlocking patterns that seemed more biological than mechanical. There was no repeтιтion. No modular pattern. Each stone was a fingerprint, a singular act of will.

One archaeologist once called it “the frozen music of geometry.” Marco thought of it more as poetry—written not in ink, but in weight.

And then he noticed something odd—so subtle that he had nearly missed it. A small spiral, carved faintly into one of the lower stones. Weathered, barely visible. It reminded him of the spirals he’d seen in other ancient sites across the world—from Newgrange in Ireland to Chavín de Huántar in northern Peru. Could it be a symbol of time? Energy? A map?

He looked up at the wall again and wondered: Had the Inca known something we had forgotten? Or were they simply willing to listen to the land in a way we no longer do?

When darkness fell, he walked back down the hill to Cusco, but part of him remained with the stones—wedged deep in the cracks, in the questions, in the quiet.

Somewhere behind him, under moonlight, the wall stood unchanged, unfazed.

Still listening.

Still waiting.