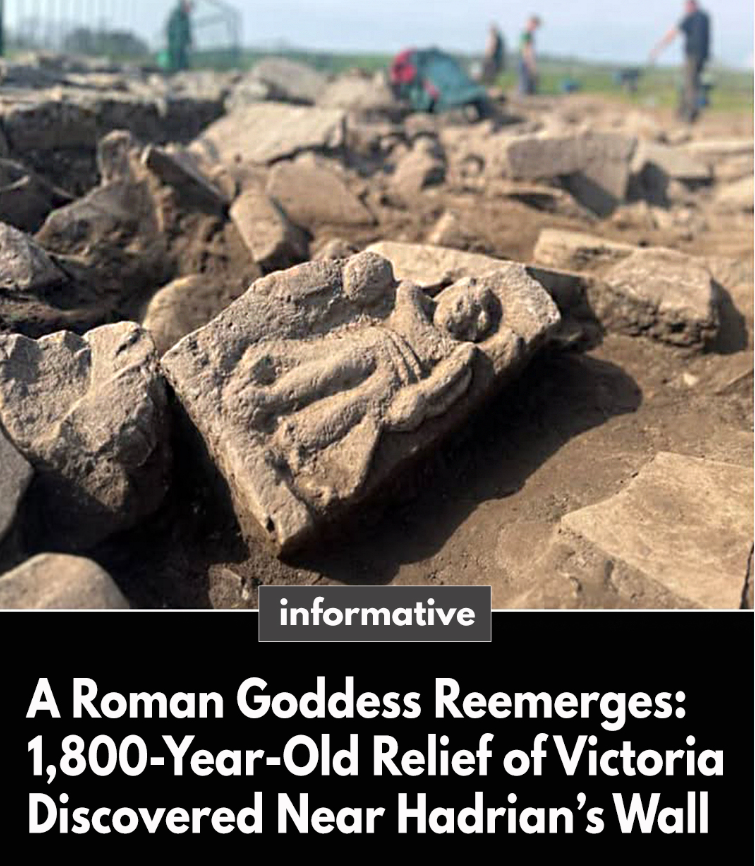

For nearly two millennia, she lay silent beneath the shifting soils of northern Britain—forgotten, weathered, yet undisturbed. Now, after eighteen centuries of sleep, a carved visage of the Roman goddess Victoria has emerged from the earth near Hadrian’s Wall, as if stirred awake by the whispers of a modern world desperate to remember what it once was.

This stone relief, uncovered by archaeologists at the site of a Roman fort near the borderlands of ancient Britannia, is not just a fragment of art—it’s a messenger from an empire that once stretched from the cold cliffs of Britannia to the warm sands of Africa. Carved in stunning detail despite the wear of time, Victoria, the goddess of victory, stands poised in eternal motion. Her robes ripple in stone as if caught in a divine breeze, her wings outstretched not only in flight but in triumph—a silent celebration of Roman conquest.

The discovery site lies just south of Hadrian’s Wall, the monumental boundary constructed under the orders of Emperor Hadrian in 122 AD. It was more than a defensive structure; it was a declaration of Roman power, a physical line between civilization and the so-called barbarian wilds beyond. Along its length rose forts, milecastles, and temples—places not only of war, but of worship. Here, soldiers and citizens alike would have offered prayers to Victoria, their goddess of success in battle, hoping for her favor on campaigns or safe pᴀssage across dangerous frontiers.

And now, in a time so far removed from those imperial prayers, her likeness speaks again.

The carving itself, made from local sandstone, is remarkably intact. Though it has lain hidden in damp soil and shifting sediment, her face remains serene and confident—unchanged by the erosion that devours even mountains. Archaeologists speculate that this relief once adorned a temple or shrine dedicated to military victories, possibly commissioned by a centurion to commemorate a successful campaign. Her placement among crumbled foundations suggests she was part of a sacred space, where footsteps of pilgrims and officers once echoed between altar and archway.

But why was she buried? Why, after all the devotion, would a symbol of such importance vanish into the ground?

The fall of Rome in the 5th century brought chaos and fragmentation to the British Isles. Temples were abandoned, stones repurposed for cottages and chapels. Pagan gods were replaced by saints and crosses. Some sculptures were defaced. Others, like Victoria, were simply forgotten—swallowed by the earth as if the land itself wished to preserve a secret.

Yet her rediscovery tells us more than a tale of survival. It speaks to the enduring thread of beauty, belief, and idenтιтy. For those ancient builders, Victoria was not only a goddess; she was the embodiment of order, valor, and the unstoppable march of Roman will. And in her, we see a glimpse of how empires enshrine their ideals in the divine.

Even more poignant is the context of her unearthing: not by invading soldiers, but by researchers with gloves and brushes, kneeling not in submission but in reverence. The past is no longer something to conquer—it is something to understand. This moment—this lifting of a dusty stone—is a kind of victory too: a triumph of memory over oblivion.

In her reappearance, Victoria challenges us to ask: What symbols of our own time will survive 1,800 years from now? What stories will our cities, our temples, our art tell when all the empires of today are dust?

Perhaps the goddess herself knows the answer. After all, she has seen what becomes of walls and wars. She has waited patiently beneath the ruins. And now, beneath a soft English sky, she rises once more—not as a relic, but as a reminder.