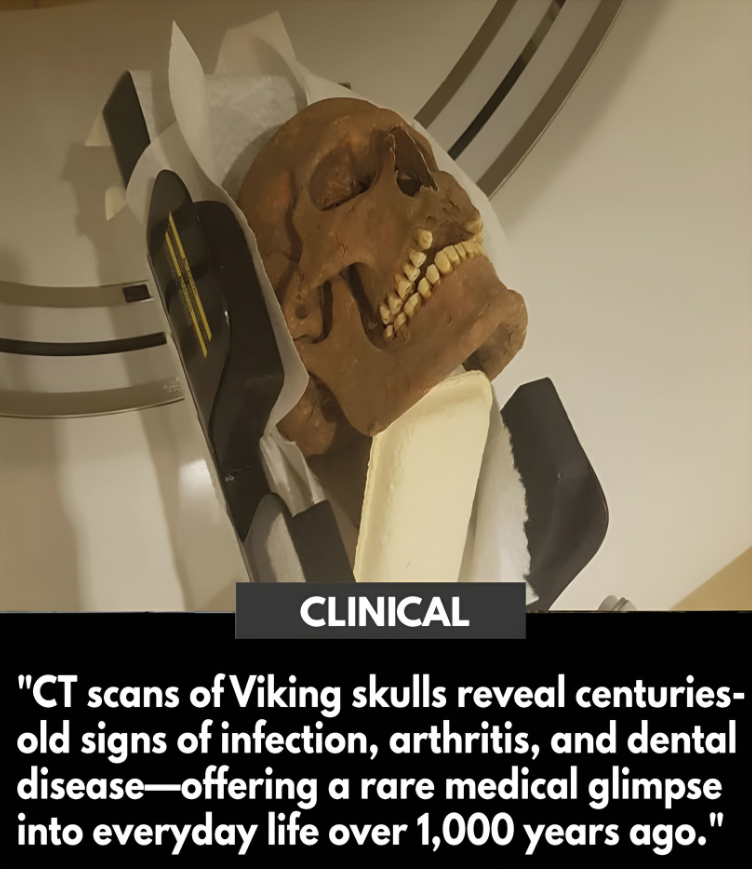

In a sterile room filled with the quiet hum of machines, a thousand-year-old skull rests inside a modern CT scanner. It is cradled with care—tucked in with soft pads, its worn teeth slightly bared in a grimace that is both human and haunting. The bone is cracked and dry, the color of aged earth, yet its presence speaks volumes. This is not just an artifact. This is someone.

He may have once been a warrior, a fisherman, a father—or perhaps all three. Now, centuries later, he has become something else entirely: a patient.

The CT scanner begins its slow sweep, the machine’s modern breath brushing across bone that once knew sunlight, snow, and the salt spray of the northern seas. Scientists stand behind a glᴀss parтιтion, watching ancient pixels light up with new life. They are not just observing anatomy; they are witnessing history written in calcium and decay.

A Glimpse Into a Forgotten World

The skull belonged to a Viking—one of the seafaring Norse people who once roamed the icy waters and unforgiving landscapes of Scandinavia and beyond. From roughly 800 to 1100 AD, these men and women shaped the world with their ships, their trade routes, and their fire-forged myths.

But the sagas never mention toothaches. They don’t speak of aching joints, impacted molars, or the slow infection that eats away at the jawbone. That’s where archaeology picks up the story the poets left behind.

Through CT scans—technology typically reserved for living patients—scientists can peer beneath the surface of ancient bone to reveal the intimate, silent sufferings of the past. Infection leaves telltale shadows in the sinuses. Arthritis wears down joint surfaces. Dental disease leaves abscesses in the jaw, visible now in grayscale on a computer screen.

What emerges is not just a skull—it is a biography written in pain.

The Warrior’s Wounds

This particular Viking, perhaps in his 40s at death—a respectable age for the time—shows signs of chronic infection near the upper teeth. Researchers note bone loss and swelling patterns that suggest a slow, agonizing march toward decay. There was no Novocain in the 10th century. No antibiotics. Whatever pain this man felt, he bore it in silence, perhaps hidden behind the same stoic mask now etched forever into his skeletal face.

His teeth are worn flat—possibly from a diet rich in gritty bread or dried fish, or perhaps from using his teeth as tools, a common habit in Viking communities. CT scans also reveal signs of osteoarthritis in the neck vertebrae, an indicator of heavy labor, possibly from rowing longships or hauling goods over rough terrain.

Forensic archaeologists study these clues with reverence. Each mark, each lesion, is a whispered testament to a life lived in motion, in hardship, and in resilience.

From Soil to Scanner

The skull was uncovered in a Viking graveyard on the windswept coast of Denmark, where the soil still remembers the weight of longhouses and the rhythm of oars striking water. He was buried with little ceremony—no sword, no precious grave goods—just a simple interment in the earth, like hundreds of others.

Yet now, he is receiving the most detailed medical examination in a thousand years. This is the paradox of time: in life, he may have been poor or forgotten. In death, he has become a voice for a civilization.

It took months of careful excavation, cleaning, and preservation before the skull was ready for imaging. Then came the scan. The images revealed not just pathology, but personality. A slightly crooked jaw. Evidence of an old, healed nasal fracture—perhaps from a brawl, or a fall on icy ground. The human story is sтιтched into every contour.

The Human Face of Archaeology

To look at these scans is to witness empathy at its highest resolution. This isn’t just about data or diagnosis—it’s about restoring humanity to history.

Too often, we see ancient people as abstractions: warriors, raiders, traders. But they had bad backs. They limped. They got sick. They grew old. Their teeth hurt. They held onto their children as the winters grew long, and some of them didn’t make it.

And yet they endured. That’s what the CT scans show most vividly—not just suffering, but survival.

Modern medicine allows us to see what our ancestors couldn’t: the slow toll of life on the body. But in doing so, we also see something more—the durability of the human condition, the universality of pain, and the threads that connect us to people who lived and died a thousand years ago.

Legacy Through Bone

This one skull, this one man, tells us that history isn’t only found in swords and sagas. It’s found in the quiet, clinical spaces of hospitals and labs where science meets soul. It’s in the meticulous attention of the researcher aligning a scanner, the reverent silence of the technician watching the monitor light up with patterns of ancient disease.

He is no longer just a skeleton. He is a patient. He is a teacher.

His bones are data, yes—but they are also memory. They hold the memory of long winters, aching joints, nights without sleep. And they hold the unspoken strength of a people who braved cold seas not just with weapons, but with weary bodies and fierce resolve.

What We Leave Behind

In the end, the Viking skull resting in the CT machine is not just a relic. It is a mirror.

It reflects our curiosity, our compᴀssion, and our unending desire to understand who we are by learning who we were. The lines etched into bone are not unlike those drawn into our own lives: paths shaped by struggle, resilience, and the quiet hope that someone, someday, might try to understand us too.

So we ask: what will future scientists learn from our bones? What stories will they reconstruct from the shadows of our suffering? And more importantly—will they remember, as we now remember this man, that behind every scan is a soul?