In the silent galleries of the Louvre Museum, where whispers of antiquity linger in the air and the past seems only a breath away, one figure stands with unmistakable grandeur. It is neither fully man nor beast—neither wholly myth nor mundane reality. With the wings of an eagle, the body of a lion or bull, and the solemn face of a human crowned in divine regality, the Lamᴀssu is a fusion of the natural and the supernatural. Carved nearly three thousand years ago in the heart of ancient ᴀssyria, it remains one of the most powerful symbols of Mesopotamian civilization, etched not only into stone but into the very soul of human history.

Its form radiates strength and serenity. Standing over four meters tall, each Lamᴀssu guarded the entrances of great palaces like that of King Sargon II in Dur-Sharrukin (modern-day Khorsabad, Iraq). Their role was far more than decorative. They were guardians—keepers of balance between worlds, defenders of kingship, protectors of sacred thresholds. To pᴀss beneath them was to step from the ordinary into the realm of the divine.

But who were the people who envisioned such creatures? And what stories whisper beneath the chiseled curls of its beard, the rippled feathers of its wings?

A Civilization in Stone

The Lamᴀssu belongs to the glory days of the Neo-ᴀssyrian Empire, a civilization that flourished between the 9th and 7th centuries BCE, dominating the ancient Near East with military might and architectural brilliance. ᴀssyria’s kings—Ashurnasirpal, Tiglath-Pileser, Sargon, and Sennacherib—constructed cities that rivaled the imagination: cities of ziggurats, canals, libraries, and mᴀssive walls. But no structure was complete without the presence of these divine protectors.

Each Lamᴀssu was a theological statement. The lion’s body represented terrestrial power—raw physical strength. The eagle’s wings symbolized dominion over the heavens, swiftness and divine reach. And the human head spoke of wisdom, intelligence, and command. Together, they formed an idealized image of a ruler: strong, swift, and wise. Carved in high relief along palace walls or as colossal sculptures flanking doorways, they stared outward with unwavering vigilance.

Cuneiform inscriptions often decorated their sides, detailing royal accomplishments and divine blessings. These were not simply artworks—they were declarations of divine right, warnings to enemies, and promises to the gods.

The Gaze of the Lamᴀssu

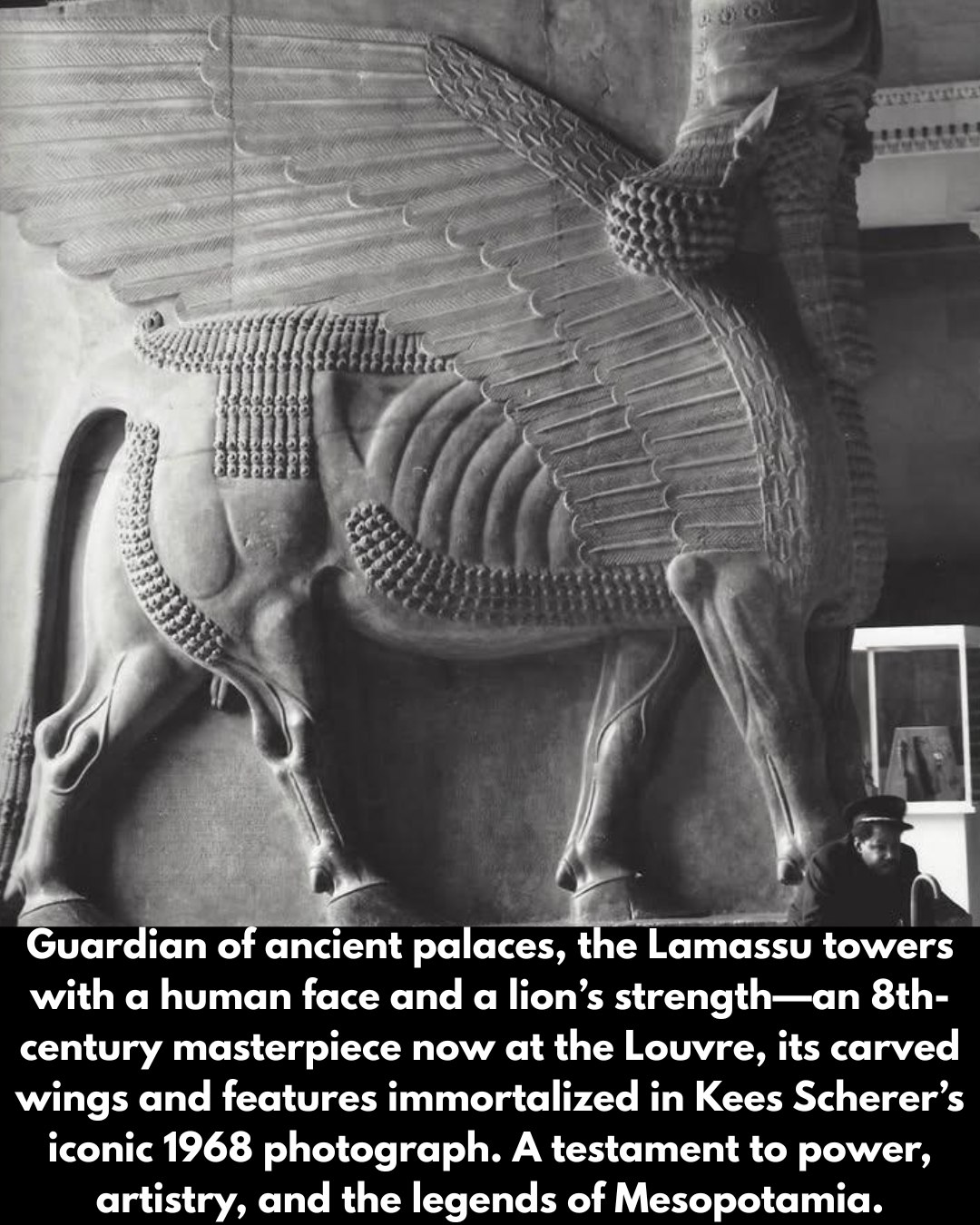

In 1968, Dutch pH๏τographer Kees Scherer captured one such Lamᴀssu in a now-iconic black-and-white image. The pH๏τo, though still, seems to pulse with power. The Lamᴀssu’s gaze, frozen in stone for over two millennia, stares directly into the future, as if daring time itself to forget it. Beside the sculpture stands a man—tiny in comparison, almost reverent in posture. The pH๏τo is a moment suspended: a modern world bowing before an ancient soul.

That image came to symbolize something deeper—the tension between fragility and endurance. Empires fall, cities burn, languages die, and yet this guardian remains. Mute but eloquent.

Excavation and Exile

The Lamᴀssu’s modern story is also one of survival and displacement. In the mid-19th century, European archaeologists began exploring the buried ruins of Mesopotamia. Men like Paul-Émile Botta and Austen Henry Layard uncovered whole palaces, their corridors lined with alabaster reliefs and statues of immense size. These discoveries electrified Europe.

But with discovery came removal.

Many Lamᴀssu figures were taken from their homeland—sawn into sections, hauled over deserts, loaded onto ships—and transported to museums in London, Paris, and Berlin. The Lamᴀssu in Scherer’s pH๏τograph, for instance, was moved to the Louvre, where it still dominates a gallery room, a silent ambᴀssador of a lost empire.

The debate over cultural heritage and the ethics of such removals continues to this day. Are these beings prisoners of history? Or messengers?

Symbolism Beyond Time

To the ᴀssyrians, the Lamᴀssu was not just stone. It was alive in spirit, invoked in prayers and feared by enemies. People believed that such divine beings could ward off evil spirits and ensure the stability of the kingdom. Their presence at gateways—liminal spaces between one realm and another—was deeply symbolic.

This notion of hybrid guardians is not unique to Mesopotamia. The Egyptian sphinx, the Greek griffin, and the Hindu Nandi all echo similar roles. Across cultures and continents, humans have always turned to symbolic creatures to represent what they cannot fully explain—divine protection, cosmic order, eternal vigilance.

Yet there is something distinctly Mesopotamian in the precise geometry of the Lamᴀssu. Every curl in the beard is methodical. Every feather is aligned with purpose. Even the feet—five, not four—are crafted so that whether viewed from the front or the side, the Lamᴀssu appears to stride forward, always in motion, always watching.

War and Loss

Tragically, many Lamᴀssu did not survive the ravages of modern conflict. In the 2010s, extremist groups in Iraq deliberately destroyed ancient ᴀssyrian sites like Nineveh and Nimrud, reducing priceless artifacts to dust in acts of calculated cultural erasure. The footage of militants hacking away at 3,000-year-old Lamᴀssu statues sent waves of horror across the globe.

It was not just stone that was shattered. It was memory.

These losses make the surviving Lamᴀssu all the more precious. They are among the few remaining bridges to a time when kings called themselves “the great ones,” when scribes recorded the deeds of the divine, and when stone could speak of empire.

Standing Before the Guardian

To stand before a Lamᴀssu today—whether in the Louvre, the British Museum, or Iraq’s National Museum—is to feel small in the best possible way. It is to be reminded that civilizations rise and fall, but the longing for order, protection, and meaning is eternal.

The Lamᴀssu asks us to look beyond the surface. To consider how strength can be beautiful, how power can be wise, and how history—though fractured—is never silent.

And perhaps that is why they endure. Not because they were made of durable stone, but because they were shaped by ideas that still matter: the fear of chaos, the desire for harmony, and the belief that somewhere, there is always a guardian watching.

#LamᴀssuLegacy

#Ancientᴀssyria

#MesopotamianMyths

#StoneGuardians

#LouvreHistory

#KeesSchererPH๏τograph

#HybridSymbols

#EmpireAndArt

#MythicalCreaturesOfThePast

#EchoesOfTheAncients