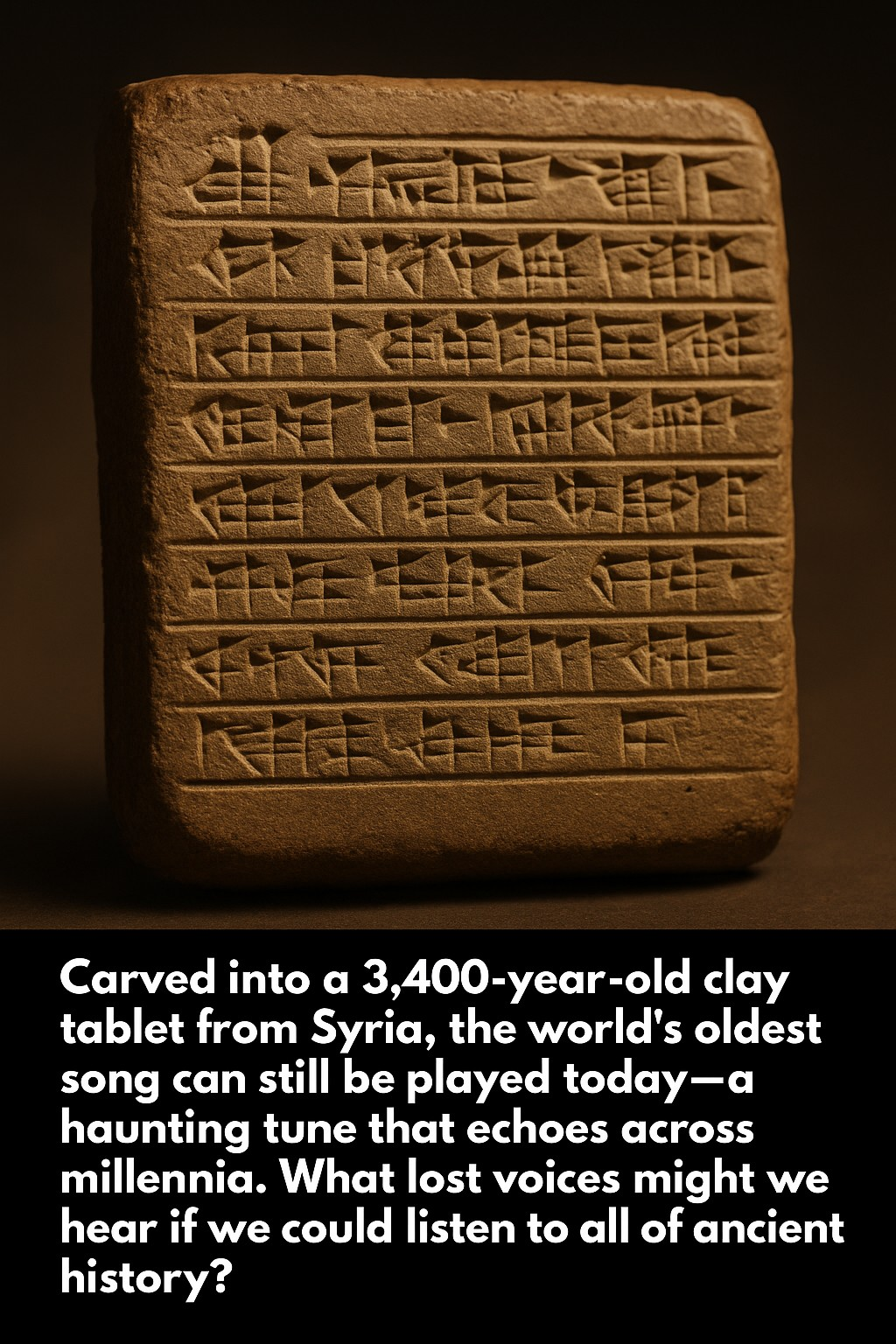

In a dimly lit museum, sealed behind a pane of glᴀss, rests an unᴀssuming slab of baked clay—weathered, chipped, and pressed with strange wedge-shaped markings. To the untrained eye, it appears as yet another artifact from the lost world of Mesopotamia. But hidden within this fragile tablet lies something astonishing: music. Not just any music—but the oldest written song known to humanity, composed more than 3,400 years ago in the ancient city of Ugarit, in what is now modern-day Syria.

Long before Beethoven, before Pythagoras explored harmonics, before the Psalms echoed in temples—this melody was already alive. It was sung by a voice now long gone, accompanied perhaps by a lyre under torchlight, heard by ears long since turned to dust. Yet somehow, across millennia of silence and soil, the song survived. A whisper from a vanished world, it calls to us still.

Unearthing Ugarit

Ugarit was a thriving port city on the Mediterranean coast during the second millennium BCE. It was a nexus of trade and culture, where merchants, scribes, and priests shared not just goods, but ideas—mathematics from Babylonia, myths from Egypt, and scripts from Sumer. It was here, beneath the ruins of a palace and temple complex, that archaeologists in the 1950s unearthed a cache of clay tablets.

Among them was one marked in cuneiform, but unlike the others filled with contracts, rituals, or royal decrees, this one carried a different energy. The tablet, catalogued as “Hurrian Hymn No. 6,” included something utterly rare: a set of musical notations alongside lyrics—a hymn dedicated to Nikkal, the goddess of orchards and fertility.

It was the first proof that ancient music could be not only imagined, but read, interpreted, and played again.

Cracking the Code

Deciphering the song wasn’t easy. The Hurrian language had long been extinct, and musical notation in the Bronze Age wasn’t exactly standardized. Unlike today’s sheet music, there were no staves, no clefs, no easy tempo markers. What scholars had instead were columns of numbers and intervals, accompanied by instructions for a singer and lyre player.

After decades of debate, in 1972, musicologist Anne Draffkorn Kilmer proposed a reconstruction based on comparative studies of Babylonian musical theory. Using a seven-note diatonic scale—surprisingly similar to the Western musical system—she produced a version that could be performed.

The result? A solemn, almost eerie melody. It moves slowly, hesitantly, like a prayer carried by wind through stone columns. It is not triumphant, but tender. Not grand, but intimate.

And in that sound—echoing for the first time in over three millennia—something stirred in listeners. The voice of someone long ᴅᴇᴀᴅ had returned.

The Human Thread

Imagine the scene: a singer in a temple courtyard, beneath a starlit sky. Perhaps a priestess, robed in linen, surrounded by flickering oil lamps and the scent of incense. Her fingers pluck at the strings of a lyre, each note resonating against mudbrick walls. Her voice rises in devotion to Nikkal, calling for blessings on orchards, for fertility, for abundance.

There is something profoundly human in that moment. It transcends language, culture, and even belief. Music, after all, is the most direct expression of emotion. It speaks to longing, to joy, to grief—and it does so without the need for translation.

This tablet doesn’t just teach us what the Hurrians sang—it reminds us that they felt.

What Else Lies Buried?

If one clay tablet could hold a melody, what else might the ancient world still be singing?

In Babylon, court musicians tuned lyres to modal scales now lost to time. In Egypt, chants echoed in the great temples of Karnak and Luxor, honoring gods with harmonies only the priests remembered. In Greece, music flowed through epic poetry and theatre, and in China, bronze bells rang in tonal systems we are only beginning to understand.

All of these civilizations left behind fragments—carvings, instruments, hymns scratched into stone. But the Hurrian hymn stands alone as the earliest complete song we can reconstruct.

It is, in a way, the Big Bang of written music.

Lost Voices and Lingering Echoes

But what of the singer? What of the hands that shaped this clay, the lips that whispered the lyrics, the heart that composed this ancient prayer?

Their names are lost. Their graves, unmarked. Yet, through this song, they survive.

It is a humbling thought—that a woman, perhaps forgotten even by her own people within a few generations, could reach across 34 centuries and stir the hearts of modern listeners. It gives us pause. It challenges our notion of permanence. It asks: what will survive of us? Our voices? Our emotions? Our art?

A Bridge of Sound

Today, musicians and scholars continue to reinterpret the Hurrian hymn. From classical renditions to digital recreations, artists around the world are breathing new life into this ancient tune. Each interpretation is slightly different—like the light hitting an old mosaic from a new angle. And with each performance, we don’t just hear the song—we complete it.

We become part of it.

It is a collaboration across time: between the ancient composer, the archaeologist who found the tablet, the linguist who read it, the musician who played it, and the listener—you, sitting in your own age, your own moment, hearing the same notes once played beneath the stars.

An Invitation from the Past

The Hurrian Hymn is more than just music. It is a call from the deep past. It is an invitation to remember that beneath all our ruins, all our wars and wonders, the core of humanity has always yearned to express itself. Through rhythm. Through melody. Through art.

It is a reminder that our ancestors were not so different from us. They too had dreams, sorrows, and joys. They sang them into the air, and somehow—miraculously—those songs endure.

So next time you hear a haunting tune, drifting in minor notes from a distant land, ask yourself: could it be a memory, a relic, a voice from long ago?

And what would happen if we listened just a little more closely?

#OldestSongEver

#HurrianHymn

#AncientMusic

#ClayTabletSecrets

#EchoesOfThePast

#MusicOfCivilizations

#ArchaeologicalMelody

#SyriaHistory

#BronzeAgeSong

#WhispersFromUgarit