Archaeologists working at the Phoenician site of Tell el-Burak in Lebanon have uncovered an intriguing discovery that sheds new light on Iron Age construction technology. In a Scientific Reports paper, scientists describe the first known use of hydraulic lime plaster in the region, with a surprising level of innovation achieved through recycling ceramic fragments.

Reconstruction of the wine press at Tell el-Burak. Credit: A. Orsingher et al., Antiquity (2020)

Reconstruction of the wine press at Tell el-Burak. Credit: A. Orsingher et al., Antiquity (2020)

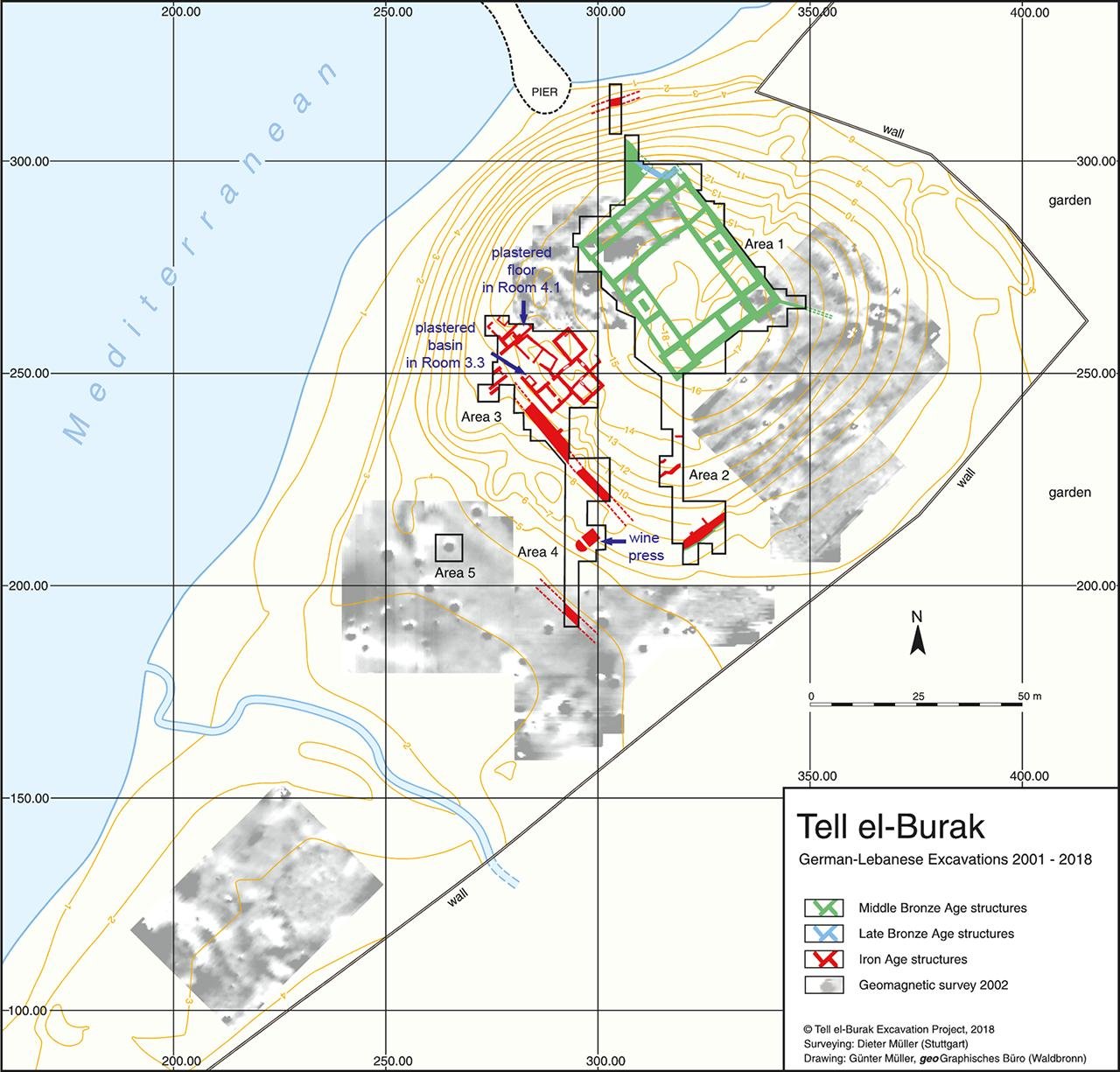

Tell el-Burak, located near the southern coast of Lebanon, was an early agricultural site occupied between 725 and 350 BCE. At the site, archaeologists found such facilities as a large wine press—believed to be Lebanon’s oldest wine press—as well as plastered basins and floors that made up part of a larger agricultural complex. These structures, though varied in function, had one feature in common: they were coated with a distinctive plaster different from standard ancient lime mixtures.

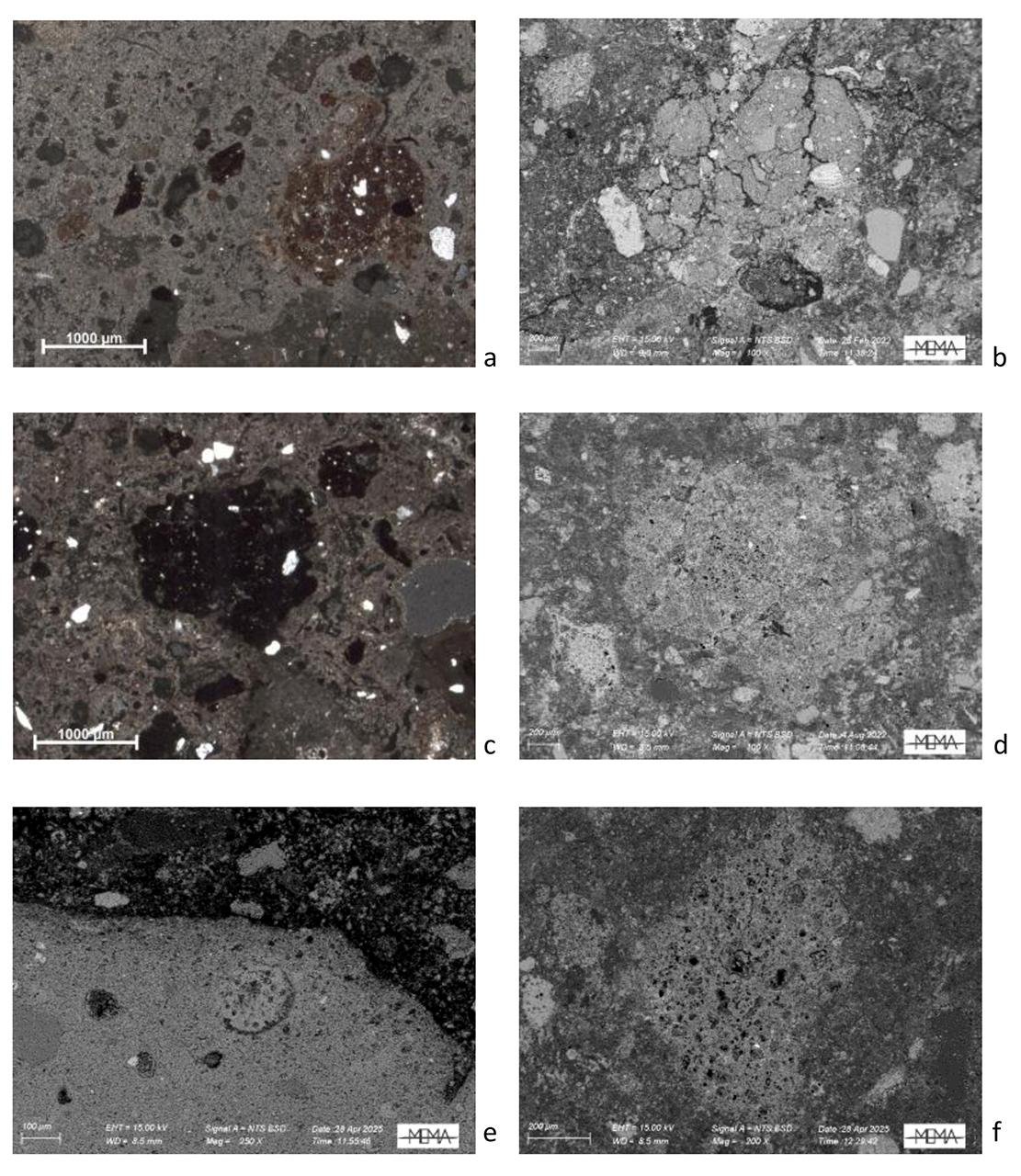

To identify the composition and purpose of this plaster, the researchers conducted an extensive analysis of the material using a combination of techniques, including polarized light microscopy, X-ray diffraction, scanning electron microscopy with energy-dispersive spectroscopy (SEM-EDS), and thermogravimetric analysis. These techniques confirmed that the plaster contained lime and locally available sand, but also a high level of crushed ceramic fragments.

Plan of the settlement at Tell el-Burak. Credit: S. Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

Plan of the settlement at Tell el-Burak. Credit: S. Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

The occurrence of ceramic material was not accidental. Microscopic analysis confirmed that the lime binder and ceramic fragments had reacted to form distinctive reaction rims. These chemical reactions indicate that the ceramics were deliberately added to enhance the properties of the plaster. The result was a mortar that would harden in the presence of water—a key characteristic of hydraulic plaster. This type of mortar would have been particularly useful in a wine press, where it would be exposed to constant moisture and would otherwise erode more fragile materials.

Tell el-Burak, plastered installations: (a) Area 4, the wine press, from the west. (b) Area 3, the plastered basin in Room 3 of House 3, from the southwest. (c) Area 3, the plastered floor in Room 1 of “House 4”, from the northeast (courtesy of the Tell el-Burak Archaeological Project). Credit: S. Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

Tell el-Burak, plastered installations: (a) Area 4, the wine press, from the west. (b) Area 3, the plastered basin in Room 3 of House 3, from the southwest. (c) Area 3, the plastered floor in Room 1 of “House 4”, from the northeast (courtesy of the Tell el-Burak Archaeological Project). Credit: S. Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

This discovery is significant because it indicates that Iron Age building in the southern Phoenician region had developed a form of hydraulic mortar several centuries before the traditionally accepted Roman use of pozzolanic materials like volcanic ash. The Tell el-Burak mortar was not derived from volcanic components or organic additives; instead, its resistance to water was achieved through the use of broken pottery, a locally available material.

The plaster was found in a number of areas at the site, which means that this technique was not an isolated experiment but part of a larger craftsmanship tradition. The fact that this material was consistently used in several installations makes it clear that the builders had an advanced understanding of how to modify lime-based plasters to suit a broad variety of functions, from juice extraction in the wine press to lining basins and floors.

Thin section micropH๏τographs showing two different types of ceramic aggregates: (a) Type 1, polarising microscope, XP; (b) Type 1, BSE image at high magnification; (c) Type 2, polarising microscope, XP; (d) Type 2, BSE image at high magnification; (e) Type 1, BSE image at high magnification; (f) Type 2 with bloating pores, BSE image at high magnification. Credit: S. Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

Thin section micropH๏τographs showing two different types of ceramic aggregates: (a) Type 1, polarising microscope, XP; (b) Type 1, BSE image at high magnification; (c) Type 2, polarising microscope, XP; (d) Type 2, BSE image at high magnification; (e) Type 1, BSE image at high magnification; (f) Type 2 with bloating pores, BSE image at high magnification. Credit: S. Amicone et al., Scientific Reports (2025)

This research disproves the traditional explanation of technological development in ancient construction, especially the one that focuses on Roman innovation. Instead, it highlights the ingenuity of earlier cultures like the Phoenicians, who reused available materials and developed effective construction techniques years before such techniques gained widespread recognition. The Tell el-Burak find contributes to our understanding of ancient engineering and suggests that hydraulic mortar expertise was more widespread—and developed sooner—than previously thought.

The study also opens doors to further investigation of ancient construction materials. Through analysis of other sites along the Phoenician coast, archaeologists may find similar applications of recycled ceramics and understand more about the regional technology networks.

More information: Amicone, S., Orsingher, A., Cantisani, E. et al. (2025). Innovation through recycling in Iron Age plaster technology at Tell el-Burak, Lebanon. Sci Rep 15, 24284. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-05844-x