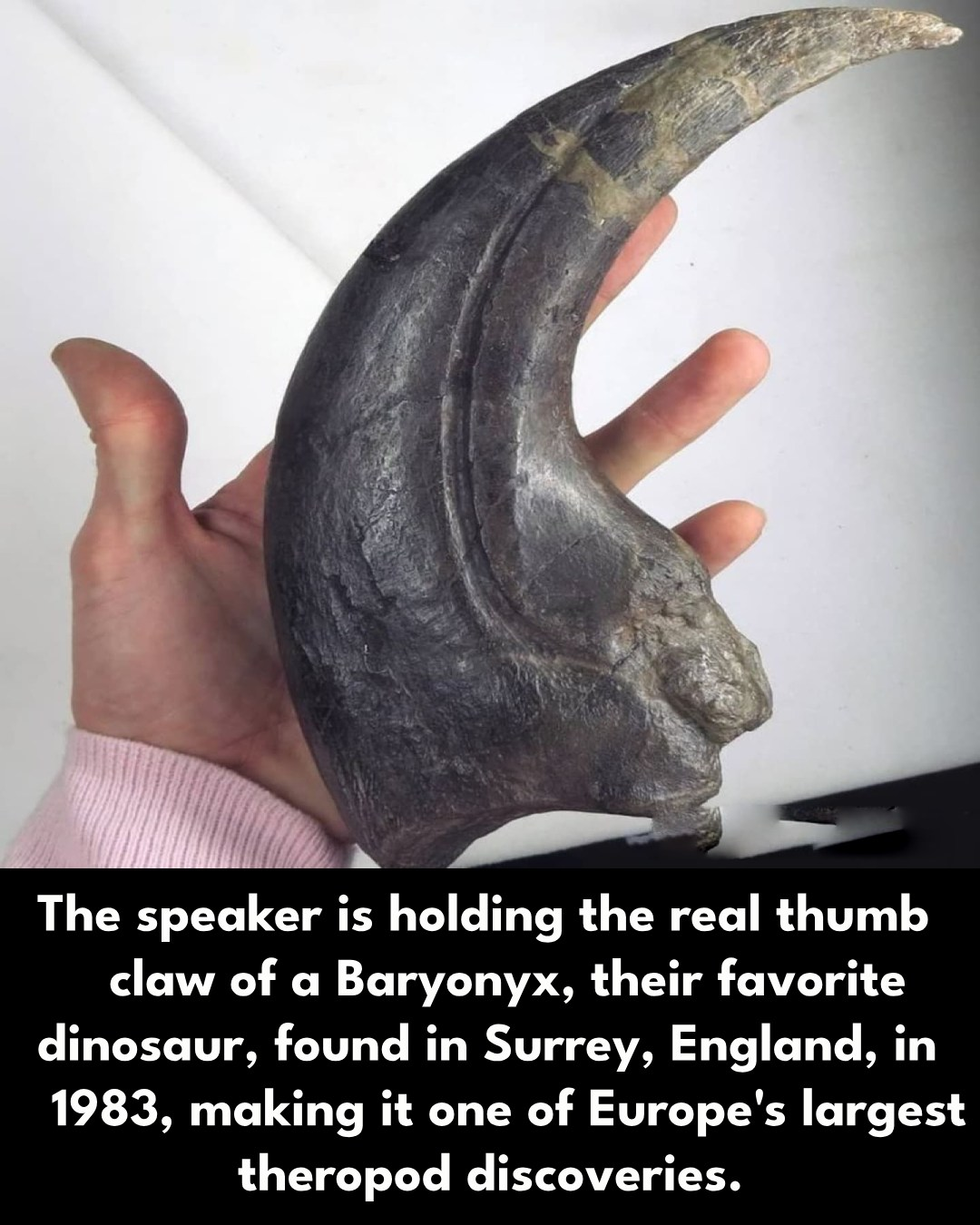

It began, not in a grand museum hall or on the pages of some dusty textbook, but in the quiet green fields of Surrey, England. The year was 1983. A man named William Walker, an amateur fossil hunter with more curiosity than credentials, was exploring a clay pit near Dorking when his eyes landed on something impossible—something no human had touched in over 125 million years. It was a claw. Mᴀssive, curved, and unmistakably ancient. What he had found was the fossilized thumb claw of a dinosaur lost to time—Baryonyx walkeri.

That claw would go on to ignite one of the greatest paleontological discoveries in European history.

Baryonyx, meaning “heavy claw,” wasn’t just another dinosaur. It was a predator unlike any other yet discovered in the British Isles. A theropod—cousin to the fearsome T. rex—but one that bore the traits of both land hunter and fisherman. It was long-snouted like a crocodile, its jaws lined with over 90 teeth, and that giant sickle-shaped claw, nearly a foot long, rested on each of its powerful thumbs. For decades, scientists puzzled over what this creature might have looked like, what it might have eaten, how it might have moved. But in 1983, thanks to Walker’s find, those mysteries began to unravel.

The British Museum of Natural History quickly launched a formal excavation, uncovering over 70% of the skeleton—one of the most complete theropod fossils ever found in Europe. Its stomach contents, still partially fossilized, revealed fish bones and even scales, making Baryonyx one of the first dinosaurs proven to have a piscivorous diet. Here was a dinosaur that swam, that fished, that straddled two worlds—land and water—millions of years before birds ever flew.

But let’s return to the claw.

Imagine holding it now, like the speaker in the image does—your fingers curled around its cold, stony form, your hand small against the arc of deep time. It’s not just a fossil. It’s a relic of a vanished world, one where shallow rivers laced through ancient forests and the sky echoed not with birdsong, but with the guttural roars of reptiles long since extinct.

To hold it is to time travel, to feel the weight of Earth’s ancient memory pressing into your palm.

And what does that do to a person?

For paleontologists and history lovers alike, it’s a kind of spiritual experience. There’s reverence in the moment—a silent acknowledgment that we are temporary, and the world is vast, old, and indifferent to our noise. In that sense, the claw is more than an object; it’s a bridge to humility.

The speaker who holds it, with a tremor of excitement and awe, likely remembers the first time they read about dinosaurs as a child. Maybe it was in a school library book filled with wild illustrations, or maybe in a museum on a family trip, staring up at a skeleton and wondering how something so big could vanish without a trace. Now, they’re not just wondering—they’re participating in the story.

What makes Baryonyx so special, even among dinosaurs, is how human its story feels.

Discovered by a man walking alone through the countryside, studied by pᴀssionate scientists who pieced together its bones like a sacred puzzle, it became a symbol of discovery itself—of how even the past can surprise us. And it didn’t come from a famous fossil bed in Mongolia or Patagonia. It came from quiet, green, rainy England—a place most would never ᴀssociate with giant predators. That in itself is a lesson in wonder: the extraordinary hiding beneath the ordinary.

Children now visit the Natural History Museum in London to see the replica of the Baryonyx skeleton. They stare at that claw, wide-eyed, and wonder if dinosaurs really once swam through ancient rivers just a few hours from where they live. The magic begins again, pᴀssed like a flame from one hand to the next.

And in homes and hearts of dinosaur fans across the world, Baryonyx has found a special place. Not as the biggest or the scariest, but as one of the most fascinating—half crocodile, half predator, all mystery.

For the speaker in the pH๏τo, that moment of holding the claw is a personal pilgrimage. It’s more than a show-and-tell item. It’s the physical proof that history, real history, isn’t just written in books. It’s buried beneath our feet, waiting to be seen, touched, remembered.

The claw you see isn’t polished. It’s raw, streaked with ancient wear, chipped by time. But that’s what makes it real. That’s what makes it powerful. Because through that imperfection, it tells a perfect story—of life, of extinction, and of rediscovery.

As you look at it, ask yourself: How many claws like this still lie undiscovered? How many more stories from Earth’s deep past wait beneath the ground? And what might happen if one day, you’re the one to find the next?

Because time doesn’t bury the past to hide it.

It buries it for us to find.