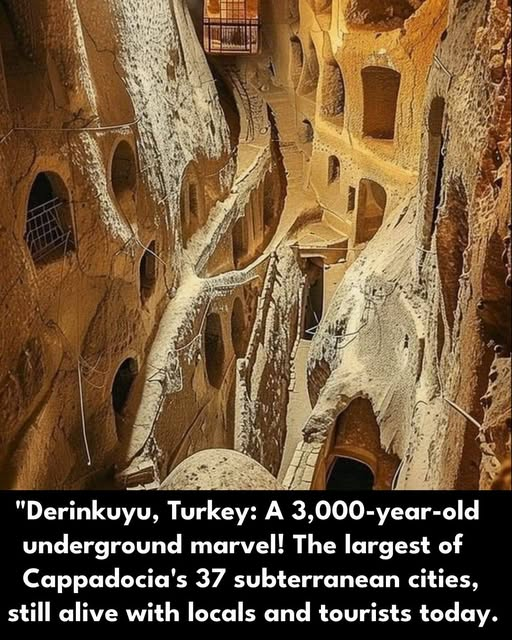

Beneath the rolling plateaus and surreal stone chimneys of Cappadocia, Turkey, lies a world few would believe if not for the tunnels themselves—vast, labyrinthine, and astonishingly alive. This is Derinkuyu, a subterranean city carved entirely by human hands, not from modern concrete but from volcanic rock softened by the ages and shaped by ancestral ingenuity. A city not of the sky, but of the shadows.

Discovered in 1963 by accident—when a local man knocked down a wall during renovations and stumbled upon a dark corridor that seemed to stretch forever—Derinkuyu has since become one of the most extraordinary archaeological revelations of the modern era. Beneath the quiet Turkish village of the same name sprawls an 18-story city, plunging over 60 meters (200 feet) into the Earth. It is the deepest of 37 known underground cities in Cappadocia, though many believe dozens more remain hidden, unexcavated, waiting in silence.

The age of Derinkuyu is still debated, but estimates stretch as far back as 3,000 years. While some scholars attribute its early layers to the Phrygians around the 8th–7th century BCE, others suggest Hitтιтe origins, possibly even older. The city was not built in a day, nor by a single people—it was layered over generations like an onion of refuge, adapted by Byzantine Christians, expanded during Arab raids, and re-purposed by countless civilizations seeking shelter from war, persecution, or simply the unforgiving climate above.

Inside, the city is a marvel of prehistoric engineering: ventilation shafts, wine cellars, churches, stables, kitchens, wells, and even schools and confession rooms. Some tunnels are wide enough to move comfortably, others so narrow they require crawling—defensive design against invaders. Huge rolling stone doors could seal off entire corridors from within, turning the city into a near-impenetrable fortress. One shaft alone supplied fresh air to the entire complex, a feat of architecture and intuition that rivals even the most modern ventilation systems.

But beyond its mechanics lies its soul. Derinkuyu was not just a bunker. It was a sanctuary. For thousands, it was home—during invasions by the Romans, the Mongols, and other ancient powers. Families lived here for months at a time, farming in secret above and sleeping in carved stone beds below. Fires flickered on blackened ceilings. The sounds of children and prayers echoed down its corridors. In its prime, the city could house over 20,000 people—an underground civilization, humming beneath the feet of the unaware.

The question inevitably rises: Why build underground at all? The answer lies partly in geography. Cappadocia’s soft tuff rock—the result of ancient volcanic eruptions—was uniquely suited for excavation. It could be shaped with basic tools, yet hardened on exposure to air. The people who lived here were not just hiding; they were adapting, surviving, and mastering the land. Derinkuyu offered not only protection but insulation—from the burning Anatolian sun and the bitter winter winds. It was cooler in summer, warmer in winter—a womb of stone, where life went on even as history raged above.

And still today, it lives.

Visitors from around the world descend into its pᴀssages, guided by electric lights and history’s whisper. You can feel the temperature drop, the air thicken, the past creep close. The walls are worn smooth by centuries of touch, the echoes of ancient footsteps still bouncing off the same stone. For a moment, you feel like an intruder in someone else’s sacred refuge—a guest in the rooms of ghosts.

Derinkuyu is more than a city. It is an idea. That survival can be beautiful. That the human spirit, when pressed beneath the weight of the world, will carve out space to breathe. Space to love, to eat, to dream. Beneath all our wars, our migrations, our upheavals, there has always been someone who said, “We will make a home anyway—even here, even underground.”

And they did.